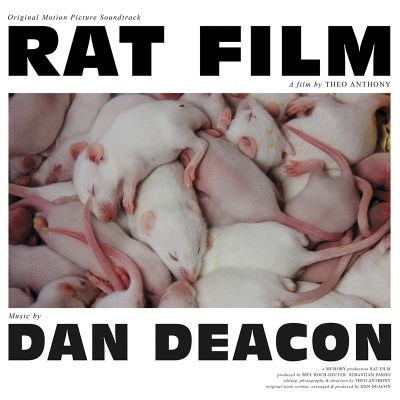

Baltimore-based composer/musician Dan Deacon did the music for Theo Anthony’s Rat Film. The film, which uses the urban rat as a way to explore a deeper story of urbanization and segregation, is a unique blend of history, science and sci-fi, poetry and portraiture. And Deacon’s music, also  a unique blend of styles, genres and instruments is the perfect match for what Anthony was doing.

a unique blend of styles, genres and instruments is the perfect match for what Anthony was doing.

In a Pitchfork review of Deacon’s album America, Jess Harvell wrote, “As carefully constructed as the work of any highbrow electronic savant you’d care to name, Deacon’s music alone should clearly paint him as a smart dude, a thinker, and a craftsman.” Deacon’s Spiderman of the Rings was named one of the best records of 2007 by CMJ New Music Monthly and Pitchfork.

We chatted by phone about the wholly unique collaboration between Deacon and Anthony for this film, Deacon’s unusual choice of instruments, another film he did the score for, the Baltimore music scene, and the magic of theremins. Oh, and about rats, of course.

So how did you come to do the music score for a film about rats?

I’ve known Theo for a long time. Just from around town, in the community of Baltimore. He was going on a long trip and I gave him an unreleased CD, something I was working on that wasn’t out yet. When he came back he said he’d like to work together. At the time he was making more shorts, more journalistic pieces, but when he started on this project, it was more experimental than what you see in the film. And he didn’t know where it was gonna go from there.

Then it kept building and my role in the collaboration kept growing, and eventually he’s making a feature about rats. I didn’t know where it was gonna go. Because it was about rats but it’s also not about rats at all. And every week I’d talk to him he’d have this energy about him, about a new exciting facet of the story.

I was pretty unfamiliar with the term “essay film” but it just clicked. It’s a project that I’m really glad to be a part of.

So what was that collaboration process with Theo Anthony like?

I was setting up a new studio in my apartment and set it up so each of us could have our own screen, so there’d be four screens total including our laptops. We could each have what section of the film that we’d be working on. So he’d be editing and I’d be coming up with music for a different section of the film and kind of watching what he was doing. We’d be looking up at each other’s work. He’d be like, “Oooh, let’s move that music to here.” Cutting to what he was working on.

When we first started I’d be watching clips that he’d give me, I’d just write to those and send him the music and not really tell him where I thought it should go. Just developing a common language of what he was going for since it was such an abstract at that point.

That really opened things up, as he was playing music in spots I never would’ve chosen. And from there we could really start digging in and mixing things up. A lot of major choices were made right up until the very last moment. Everything was malleable. Some of the pieces we liked the best ended up on the floor because they just didn’t fit.

You composed music for video and film before, right? So what was different about this one for you?

This was the first feature that I scored by myself. I scored an earlier one for Francis Ford Coppola, with someone else [for Coppola’s indie film Twixt] whom I think I had one phone call with. Budget was very different, Coppola is obviously a legendary icon of the game, and he, too, is very into experimenting and trying new things, but also had a large team around him. When we were in the recording, in the beginning of the process it was cool, there was a lot of riffing back and forth.

But then when it came to the actual work I started working less with Francis and more with his team, and the idea sort of fell apart. Like the idea of me getting [co-composer] Osvaldo [Golijov]’s orchestral stems and making new music out of those… there seemed to be a break in the line somewhere. I shouldn’t be talking shit about other projects [laughs]—this is why I should drink coffee before an interview.

It was just different. Rat Film, it was really nice to work with someone who says they’re open to anything—and they mean it. A lot of times people will be like “I don’t know what I want the music to be, I just want you to experiment!” When at the end of the day, they don’t really.

So it’s nice to work with people who are completely transparent in the collaboration process because that’s what is required for it to be a success.

Can you talk about that use of theremin and rats? I can’t imagine that’s been done too often before—or perhaps never.

That was the performance that became the catalyst for me being more involved in the film. Theo came and wanted a performance of me making music, with rats, in a beautiful church. We’re gonna have someone wearing a 3D headset with a 360 VR view of what rats would see. I started thinking of a music teacher in college who had an overhead projector with bugs on it, and each player in the quartet was assigned a different bug. And as the bug moved around that informed your playing.

So I thought about that idea. But with rats. And how we could build on that. And then thought, if we made an enclosure with theremins, the rats could control the theremin.

If you’re not familiar with theremins, they are like the classic sci-fi sound instrument [does impression of a theremin sound]… It uses hand movement without touching anything but adjusting radio waves to give it this sweeping sine wave sounds. It’s an instrument everyone’s heard, maybe even seen, if not versed in.

For some reason, I have three of these things. Theo constructed a triangular cage and put each Theremin in a corner, so when the rats would move from anywhere in the space they’d change all three of the theremins since they were in close proximity. Then we ran that into my computer and we also created audio files—we basically collected as much data as we possibly could. And used that for the basis of the rest of the score.

So when you hear the piano score for example, that is a manipulated snippet of the rats moving around the cage. So much of the score is taken from using snapshots of that experiment with those rats.

Yeah, we did. I’m pretty obsessed with player pianos. It gives it like a…it’s an acoustic but non-human instrument so it doesn’t sound like electronic music, but also doesn’t really sound like human kind of music. It’s its own unique instrument, I really love it. And it’s utilized pretty heavily in the score.

It has an otherworldly, haunting kind of feel to it…

[Hear that player piano in this piece below:]

Were you part of the process that selected Ed Schrader’s Music Beat’s “Rats” song to be in the film’s energetic theatrical trailer and at the end of film?

No, Theo already had that in mind before, they were a pretty well-known band within Baltimore. And when he told me that was going to be in the ending credits I was really excited. Because I was also simultaneously producing and co-writing their new record. Which was odd… I’d have one session with Theo for a few hours and then Ed [Schrader] and Devlin Rice and I’d be mixing this pop record, and then this experimental film score. I think they kind of blended into each other.

Even the sax player and the cellist in Rat Film are pretty heavily featured in the other record—and I can’t remember which project I had them over for originally! It’s so hard to envision the Rat Film score without Owen Gardner’s cello on it. It just made sense in my mind, tying up all the loose ends in a sitcom kind of way, “Of course Ed’s the last track in the film.” Totally fits.

Is there a lot of collaboration in the Baltimore music scene, everyone knows each other?

There’s a lot of that. It’s a good time to be a musician in Baltimore. There’s a lot of collaboration.

There’s not that many places to play as compared to some other cities. It’s weird, it’s like a shrinking and growing of the city simultaneously, because the more acts you get to see and know, the more you know them, the smaller the city feels. But then the size of the whole population you’re interacting with seems to enlarge. If that makes sense.

Who are some of your own musical influences, for your music in general and also specifically film composers? Any people you have back in mind when composing for a film like this?

Minimalists were definitely a huge influence on me, people like Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass. Especially Glass’s scores. So much are his voice. Also just the range of films he scored—I can’t think of two more different films than [the documentary] The Thin Blue Line and [the horror film] Candyman. I really loved Mica Levi‘s score for Under the Skin.

I loved Neil Young‘s score for [Jim Jarmusch’s indie Western] Dead Man—I think that’s an amazing score.

Jodorowski‘s score for his film Holy Mountain, collaboration with [jazz musician] Don Cherry was incredible. I loved Disasterpeace’s score for It Follows, I think they really slayed that one. Wendy Carlos‘ score for The Shining, that work is beyond incredible.

Oh, of course, Jonny Greenwood’s scores for PT Anderson’s films are incredible. I recently enjoyed the Phantom Thread and use of music in that film. But There Will be Blood—that’s maybe one of the most envious pieces of music that I can imagine.

You’ve lived in Baltimore and New York. Have you had run-ins with rats in the city yourself?

I moved to Baltimore 14 years ago. And yeah, just last night, as a matter of fact, I was walking to a show and a rat ran right in front of us, and we were just like, “Huh, look at that.”

What I always think about rats is, what would rats life be like without humans? I wonder how much rats love humans, or think, “why are they always leaving so much crap around?” The film goes into this to a degree—I guess any city you live in you’re gonna have rats. Any time you put that many people together in one confined area, rats are gonna say “Let’s go there, this is gonna be great.” [laughs]

Does the film make you think any differently about them?

My parents were exterminators, so I grew up—and Theo didn’t know that going into it, I think I let that cat out of the bag on that as it were pretty late—I grew up pretty familiar with guys like Harold [the exterminator in the film] who had a similar philosophy to my dad. It’s hard to see rats now and not think of the film. There’s a lot of historical context with the rat, the way it’s been used as an icon and a means of justifying horrific acts toward whole populations of people. So yeah I definitely look at rats differently.

But I also look at people differently, you know what I mean? It’s hard to hear the process of “redlining,” such overt bias and intended segregation and see it unfolding on a daily basis. And there’s always this sort of false optimism, like “it used to be f___d up.” Which is clearly not the case.

So what else will you do with your theremins? You said “for some reason I have three of those things”—why do you have three of those things?

Haven’t touched one for awhile. They do have such a haunting sound. Yeah, I have three of them. When people would play Moogfest, they’d give away theremins as a gift to the artists who played them, so I got one three years in a row! Not really sure what other uses there will be.

Maybe a science fiction film will come calling.

I think one did! [laughs]