Edward Snowden in Moscow, October 2013 (picture via Wikimedia)

Spies of Mississippi, about a previously little-known chapter in the civil rights movement, comes at a time when the subject of domestic spying continues to be on the minds of many Americans. The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission is, alas, far from the only instance of a government agency using its powers to spy on American citizens.

Certainly the ongoing Edward Snowden case has been rightfully front and center in the news and in discussions about the boundaries of surveillance. NSA (National Security Agency) whistleblower Snowden has been called everything from hero to traitor for his efforts to expose the US government’s mass surveillance programs.

But revelations of US government spying is nothing new, as Spies of Mississippi exemplifies.

The Snowden and Wikileaks cases have antecedents in a lesser-known but very important 1971 case about a group of citizen-burglars who broke into an FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania to expose how that government agency was spying not only on foreign targets but on American citizens.

They managed to anonymously send their findings to journalists, and the rest was, eventually, history. From a New York Times story on the break-in:

The author, Betty Medsger, a former reporter for The Washington Post, spent years sifting through the F.B.I.’s voluminous case file on the episode and persuaded five of the eight men and women who participated in the break-in to end their silence.

Unlike Mr. Snowden, who downloaded hundreds of thousands of digital N.S.A. files onto computer hard drives, the Media [PA] burglars did their work the 20th-century way: they cased the F.B.I. office for months, wore gloves as they packed the papers into suitcases, and loaded the suitcases into getaway cars. When the operation was over, they dispersed. Some remained committed to antiwar causes, while others, like John and Bonnie Raines, decided that the risky burglary would be their final act of protest against the Vietnam War and other government actions before they moved on with their lives.

Here’s more from that piece, with emphasis mine in bold below:

Ms. Medsger’s article cited what was perhaps the most damning document from the cache, a 1970 memorandum that offered a glimpse into Hoover’s obsession with snuffing out dissent. The document urged agents to step up their interviews of antiwar activists and members of dissident student groups.

“It will enhance the paranoia endemic in these circles and will further serve to get the point across there is an F.B.I. agent behind every mailbox,” the message from F.B.I. headquarters said. Another document, signed by Hoover himself, revealed widespread F.B.I. surveillance of black student groups on college campuses.

“Stealing J. Edgar Hoover’s Secrets,” via NY Times‘ Retro Report:

Wartime Origins

The FBI’s domestic spying campaigns were not new to the Vietnam era, either.

The NSA has origins tracing back to WWI, after the US declared war on Germany the Cipher Bureau and Military Intelligence Branch (MI-8) was formed as more of a foreign surveillance effort. These Army code breakers were once given the more intriguing name “Black Chamber” and were lead by Herbert O. Yardley, considered to be one of the greatest cryptologists of all time, and who later became a sort of Snowden of his day by whistle-blowing on American intelligence in the book American Black Chamber, which was later discredited by the NSA, who called it a “monumental indiscretion.”

This group later reformed as the Signal Security Agency (SSA) during WWII and the Armed Forces Security Agency, and then as Operation SHAMROCK at the end of WWII. Writes Ray Downs in a piece for Vice:

Operation SHAMROCK began as an Army program in 1945. During World War II, the Army had legal access to the cables of the three major communication companies of the day (RCA Global, ITT, and Western Union). But with the war over and won, that access was considered illegal, though apparently the government didn’t want to just stop listening in. According to The Lawless State: The Crimes of the US Intelligence Agencies, the Army Signals Security Agency asked the companies to [continue] to let them monitor international cables. The companies agreed, but there was a twist. As the authors of The Lawless State wrote, “The government apparently never informed the cable companies that its activity was not limited to foreign targets but also analyzed and disseminated the telegrams of Americans.”

In 1952, the NSA was created and took over SHAMROCK and soon the agency—which the vast majority of Americans had never heard of—was intercepting 150,000 messages a month.

And via a piece by the PBS series FRONTLINE, “Spying on the Home Front”:

When FRONTLINE asked how the NSA got the companies to hand over telegrams during Shamrock, Snider replied, “They asked.” The companies agreed to hand over communications without warrants. The revelation of Shamrock and other abuses by the Church Committee investigations led Congress to enact the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) in 1978. FISA set up a special secret court and set of procedures to oversee intelligence agencies’ domestic surveillance. “What Congress said is, ‘Phone company, don’t hand this stuff over to the government unless you have a warrant or other proper authority,'” explains Cindy Cohn, an attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, which in January 2006 filed suit against AT&T for allegedly illegally handing over its clients’ communications to the NSA.

More from Ray Downs:

During the Church Committee hearings in 1975, which publicly revealed the existence of the NSA in the process of looking into misconduct of America’s intelligence agencies, Lew Allen Jr., the the NSA’s director at the time, said that Congress passed a law in 1959 that “provides authority to enable the NSA as the principal agency of the Government responsible for signals intelligence activities, to function without the disclosure of information which would endanger the accomplishment of its functions.” In other words, it could pretty much do what it liked.

The NSA used that freedom, according to a Congressional investigator who discovered SHAMROCK, to establish secret facilities in several cities, including New York, San Francisco, Washington DC, and San Antonio. In each city, NSA employees would go to the major telegraph companies and copy telegrams, with the companies’ permission but without warrants.

From The Chicago 10

The Tumultuous ’60s + ’70s

Of course, one of the most famous cases of illegal government surveillance in US history is Watergate, even if it didn’t involve the public per se. We won’t go into great details about this well-known story here, but if you want a good refresher course, read Watergate by Fred Emery, or see both All the President’s Men and the recent follow-up documentary All the President’s Men Revisited. And the documentary The Most Dangerous Man in America: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers covers the gripping story of the former Pentagon insider who smuggled a top-secret Pentagon study to The New York Times that showed how five Presidents essentially, and consistently, lied to the American people about both the reasons for and the occurrences in the Vietnam War.

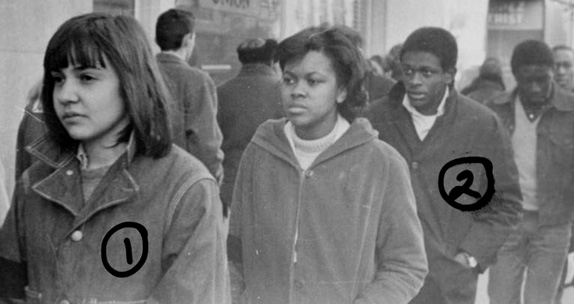

But a lesser-known, yet fascinating case study on civil liberties is the story of the Chicago 10, and more broadly the surveillance of protesters before and during the 1968 Democratic National Convention. As captured in the documentary Chicago 10, during the 1960s, police across the U.S. successfully filed class-action lawsuits that enabled them to legally spy on anti-war and other activist groups.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) mentioned above has an extensive Timeline of NSA Spying on Americans, which is rather distressingly packed with events over the past few years, not surprisingly beginning with the tragic events on September 11, 2001, which led to an expansion in the NSA’s activities and powers, alongside the creation of the “Department of Homeland Security.” This includes the involvement of American telecomm corporations, even if largely unbeknownst (for several years at least) to the American public.

More from FRONTLINE:

For more than 25 years after Shamrock was exposed, no new allegations of domestic spying by the NSA came to light. But on Dec. 15, 2005, The New York Times published an article headlined “Bush Lets U.S. Spy on Callers Without Courts,” and a firestorm erupted. According to the article, with the president’s authorization, the NSA “monitored the international telephone calls and international e-mail messages of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people inside the United States without warrants over the past three years.” Four days after the story was published, President Bush defended the program at a press conference, maintaining that it was limited to calls between suspected terrorists abroad and individuals inside the U.S.

But when Snider heard the news, he was shocked. “I was surprised that we would ever see this be raised as an issue again, because the FISA had settled that issue,” he said.

It is still unclear which telecoms have cooperated with the NSA program. On May 11, 2006, USA Today reported that the NSA was collecting Americans’ phone calls into a massive database and was getting the data directly from AT&T, Verizon and BellSouth; BellSouth and Verizon both disputed the report. In February 2006, the online publication CNET asked large telecommunications and Internet companies about their involvement in the NSA. Fifteen denied involvement and 12, including AT&T, chose not to reply.

Edward Snowden, while living under temporary asylum in Russia, recalled one of the most famous, and prescient, examples of a state in which the government knew all, even if it was ostensibly fictional:

“Great Britain’s George Orwell warned us of the danger of this kind of information,” Snowden says, referring to Orwell’s dystopian novel “Nineteen Eighty-Four,” about a superstate in a world of perpetual war and omnipresent government surveillance that persecutes individualism and independent thinking as “thoughtcrimes.”

“The types of collection in the book — microphones and video cameras, TVs that watch us — are nothing compared to what we have available today,” Snowden says in broadcast excerpts… “We have sensors in our pockets that track us everywhere we go,” he says, apparently referring to cellphones. “Think about what this means for the privacy of the average person.

From a brief but cutting interview in Spies of Mississippi, African American Representative Bennie G. Thompson, a Mississippi Democrat who serves on the House Committee on Homeland Security, says:

“You have to have boundaries, or you start down that slippery slope.”