This article was published in tandem with the Independent Lens documentary Home from School: The Children of Carlisle

By Jordan Dresser

When the Indian wars were coming to a close in the late 1800s, three little Arapaho boys made a long journey from their home in Wyoming to a new residence in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

The boys were going to attend Carlisle Indian Industrial School, in order to be assimilated from their Arapaho culture to the new white world. For some students, it was cloaked as an opportunity. For others, who were forced to attend, it was a nightmare.

Founded in 1879 by Richard Henry Pratt, Carlisle was one of the first Indian boarding schools to emerge in the United States. It ran like a military camp. The purpose of the school was to strip Indian children of their cultural identity and shape them into English-speaking students who bore no resemblance to the great tribal nations they belonged to. Children came from tribes from all over, but mostly the West. Carlisle was located on the East Coast and away from their source communities: this was an intentional tool to isolate and, in a sense, break the students.

And break them they did. The school had a cemetery that, at one time, housed 180 graves, some of them listed as unknown.

Three of the known graves belonged to Little Chief, Little Plume, and Horse. Within a year or so after arriving to Carlisle by train, on March 11, 1881, all three boys died: Little Chief, whose name became “Dickens Nor,” was 14 years old when he arrived at the school, and died on January 22, 1883; the youngest of the three, Little Plume, whose name was anglicized to Hayes Vanderbilt Friday, was 9 years old when he arrived, and 10 when he died; 11-year-old Horse, renamed Horace Washington, died just over a year later.

Descendants of Chiefs

Given their short lives, the historical information on the three boys is limited. But their lineages are known and significant. Little Chief was the son of Chief Sharp Nose, and Little Plume and Horse were descendants of Chief Black Coal and Chief Friday.

Arapahoes in Washington D.C. as part of the Sioux Delegation of 1877. Top Row, left to right: Antoine Janis, Young Spotted Tail, Joe Merrivale; seated: Touch-the-Clouds (Minnicouju Lakota), and (l-r) Northern Arapaho leaders Sharp Nose, Black Coal, and Friday [courtesy Library of Congress]

Being family of these great war chiefs made Little Chief, Little Plume, and Horse prime candidates of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School.

Yufna Soldier Wolf, a descendant of Chief Sharp Nose like Little Chief, worked tirelessly to repatriate the three boys. It wasn’t an easy task, but a necessary one that other tribes across the nation are also doing.

In the 2015 book, We Are Coming Home: Repatriation and the Restoration of Blackfoot Cultural Confidence, Herman Yellow Old Woman recounts visiting with tribal elders and declares how now is the time to reclaim what was once ours. Herman of the Siksika Nation in Canada is the great-grandson of the Weather Dance Robe maker, Yellow Old Woman. Yellow Old Woman was known as a Weather Dancer—a medicine man who maintains a spiritual connection with Natosi (the sun) and controls the weather during ceremonial occasions. In the book, he said “When we asked the Old Ladies for more advice, they told us, ‘Once you think about it or talk about it, then you can’t turn back.’ You have to do it. You might hurt yourself if you’re just going to talk about it and never do it.”

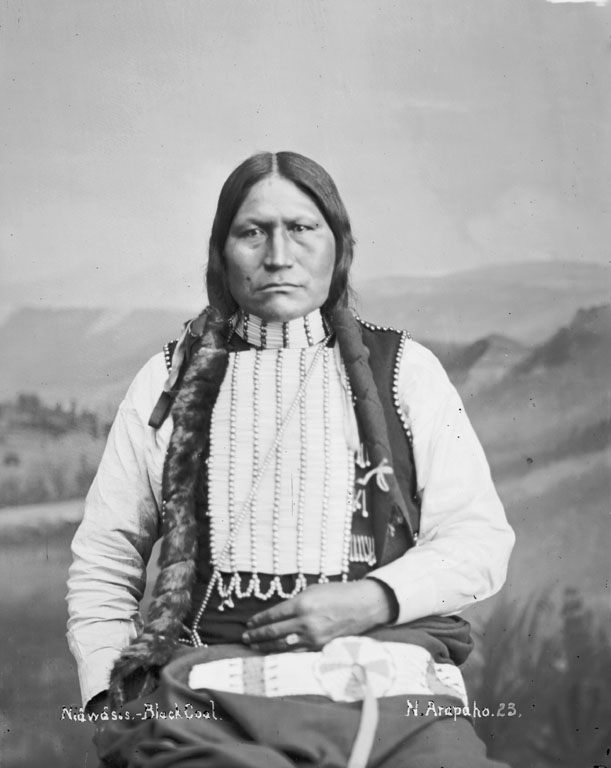

Chief Black Coal, 1882.

And Soldier Wolf did do it. In 2017, her dream became a reality: the Northern Arapaho Tribe became the first nation to successfully repatriate their children from Carlisle, which is still utilized today as a military camp for basic training.

Why Repatriation Needs to Be Done and How it Serves Native Nations

In her book, Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native America in National and Tribal Museums, Amy Lonetree asserts that repatriations have the ability to transform a community. “Tribal members can gain strength from understanding and reclaiming their rich, cultural inheritance and identity.” For Wind River, the home of Little Chief, Little Plume, and Horse, their repatriation can close a door and start the journey of healing that our people desperately need.

Watch Home From School: The Children of Carlisle on the PBS App

The Lost Lives and Imagined Potential of Little Chief, Little Plume, and Horse

Soldier Wolf believes they would’ve been something great.

Growing up, she was immersed in stories about Little Chief, Little Plume, and Horse being present during battles and helping their fathers, uncles, and other chiefs get ready for battle. As Soldier Wolf remembers: “It was up to the little guys to prepare the dog soldiers in those hand-to-hand battles. The boys’ responsibility in these times was to frantically prepare each warrior and get them ready to fight…that was the boys’ upbringing and responsibilities as they were learning how to fight and protect their tribe.”

Yufna Soldier Wolf addresses audience at a screening of Home From School, with photos honoring recently departed elders in front of her. Photo credit Zoe Friday.

One particularly vivid story about Little Chief and Little Plume sticks out to Soldier Wolf:

“They went to run ammunition, and as they rode up into a raven, they were afraid to go over the top because they didn’t know what was over the hill. They left their ponies, and when they looked over the hill, they could see a small skirmish. Arapaho men waving at them to run their ammunition. A fighter with a wolf head signaled to them, to wait for him to give them cover.

“To the two little boys, this was their heavy ammunition, and when the wolf got to them, they ran as fast they could, next to him shooting, and got to the horses that were shot lying dead. They crouched down and handed out the ammunition. The story told was that as they ran, the warrior giving cover got shot. He lay there dying. He told them in Arapaho to tell his grandma that he loved her and that he would see her again. He told the boys to not be afraid. The boys sat there with him until he passed on.

“They took his war bonnet, untied his belt that still held the stake that only dog soldiers wore. They held each other, scared to leave for their horses. They thought someone by now would have found them. They knew where to find the warrior’s grandma and that pushed them to run back to where their horses were.

“The grandma, after finding out, had to replace her [departed] grandson. They gave the warbonnet to a young warrior once the battle was over, and had a war bonnet dance. The bonnets are sacred, and these stories are told during war bonnet initiations.”

Painting of Black Man, an Arapaho warrior with face paint and feathers. By E.A Burbank, 1899.

As a producer of Home From School, I was present for the historical repatriation at Carlisle. When you are working on a film, you tend to get in a zone. Your mind is busy dealing with the logistics of capturing the story, and sometimes you can be consumed by the details. The sheer reality of this project came into clear view for me when we sat down to interview tribal elder Hubert Friday.

I have great respect for Hubert—the great-grandson of Chief Friday, who worked to maintain peaceful relations between settlers and Arapaho. Hubert is warm, funny, and fluent in our language. He reminds me of my dad. Strong men with hearts of gold. Watching Hubert get emotional while speaking in Arapaho about the three boys broke my heart. He just wanted them to go home.

As the Northern Arapaho Chairman, I see the impact of intergenerational trauma, such as Indian boarding schools, on our people every day. Not settling those conflicts, our people turn to drugs and alcohol to numb the pain. A new day never seems to come. But healing is possible. Our tribe offers services, like White Buffalo Recovery Center, to heal those wounds and help our people become their highest selves.

Hubert Friday outside Carlisle Indian Cemetery, Carlisle, PA.

Cree Reporter Connie Walker created a podcast for CBC Radio called Missing and Murdered: Finding Cleo. Walker tells the stories of the Missing Murdered Indigenous Peoples epidemic and the impact it has on our communities. In Canada, boarding schools are called residential schools. Despite the different name, they still have the same negative impact. Earlier this year, one residential school unearthed over 700 children buried in a mass grave.

The podcast follows a Cree family’s search for their missing sister, Cleopatra “Cleo” Semaganis Nicotine, and attempts to uncover why she and her five siblings were taken into government care in the early 1970s, and subsequently adopted into non-Indigenous families in Canada and the United States. This was part of a wave of apprehensions, later called the “Sixties Scoop.” Cleo died tragically at the age of 13. Two of the siblings were reunited through the show.

In an interview with the Columbia Journalism Review, Walker noted how we feel this impact today: “The podcast is really an exploration of the trauma that children experience, about what Cleo and her siblings experienced when they were taken from not only their communities and their families, but (from) their siblings as well. That’s had a lifelong impact.”

I thought of that quote recently when I attended a screening event of Home From School at Colorado State University in Fort Collins. Colorado is the homeland of the Arapaho people.

To start the event, a drum group began to sing. A little girl wearing sparkly Crocs sat at the drum and took out a drumstick. The drum is considered the heart of the people. She slowly started to hit the drum and could watch the other two men also sitting at the drum. She was trying to find the rhythm. She quickly found it. As the song built, she was in sync and each beat became louder. It was beautiful.

The history of boarding schools and what they did to us as tribal people have been heartbreaking. But there is also hope. And on that day at the film screening, a little Indian girl found her heartbeat.

> Read more about Yufna Soldier Wolf’s father, Mark Soldier Wolf, and her family.

Jordan Dresser is the Chairman of the Northern Arapaho Tribe located on the Wind River Indian Reservation in Wyoming. He graduated from the University of Wyoming with a Bachelor of Arts in journalism. He has worked as a reporter for the Lincoln Journal Star, Salt Lake Tribune, the Forum, and Denver Post. Questions of who owns tribal artifacts and the role tribal members play in these decisions prompted Dresser to leave Wind River and enroll in a Museum Studies Graduate Program at the University of San Francisco. In 2016, he co-produced the PBS documentary What Was Ours, followed by The Art of Home: a Wind River Story (Wyoming PBS). Prior to becoming the Chairman of the Tribe, Jordan served as the Collections Manager for the Northern Arapaho Tribal Historic Preservation Office. Jordan describes himself as a storyteller who uses words, images, and objects to paint an accurate picture of tribal nations. He is directing and co-producing Who She Is, an animated documentary short series about the MMIW/P (Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women/People) epidemic in Wyoming.