A small square of origami paper can be folded into an infinite number of complicated shapes. Similarly, Vanessa Gould’s documentary career has become surprisingly complex after her first film, Between the Folds, which spotlighted origami leaders throughout the world. The paper-folding craft took her from exploring mathematics and art to obituary writers and climate change. She says they all hold something essential in common — questions about the nature of life and death.

Since the making of the 2008 film, many of the artists, scientists, and paper geeks in Between the Folds are still practicing origami. Sadly, the preeminent origami artist Eric Joisel passed away in 2010. Gould was determined to preserve his legacy, and helped The New York Times report his obituary. This led her to her latest documentary project about the obit writers at The New York Times.

In addition to the twists and turns in her career, Gould talked to us about the similarities between art and science, her favorite conceptual documentaries, and her own attempts at folding Joisel’s beloved origami rat (and shared a picture of her handiwork!).

What got you so interested in origami?

Basically, I heard about mathematicians who were doing it for mathematical reasons and, at the same time, what they were making was beautiful to look at. So, first I got interested in origami’s connections between aesthetics and science. As I learned more, I started to see some hidden ways of exploring deeper connections between art and science, right brain and left brain — and the pretty profound ideas behind turning 2D into 3D. Those things made origami fascinating to me, not just the steps of folding and things like that.

Who are some of your favorite thinkers who mesh science and art?

Musicians, filmmakers, and architects tend to get pretty deep into ideas of form. And into

the art-science connection. Buckminster Fuller did a lot of stuff I admire. Filmmakers Chris Marker and Jordan Belson. The composer Terry Riley. Alexander Calder, the sculptor.

What in your life drew you to be interested in the connection between science and art?

I think, just by being human, nearly everyone must be interested in it to some degree.

Because it’s the age-old questions about the universe and how we experience it. You can

go after it in a quantitative or qualitative way, but it’s the same thing: When we stare at the sky, how do we understand what’s around us? Where do we fit in? Why is that moving or beautiful? And why have we been asking those questions for so long?

It feels like we are made to ask those questions. For me, the differences never felt as distinct as the similarities. With origami, I was looking for some unexpected exploration of that fundamental common ground — of how art and science are two tools in the same eternal and evolving investigation.

After learning more, it became clear that the square mirrors the things the folders are

investigating. To an artist, a form that draws them in. To a scientist, the materialization of a theory that draws them in. After time, those differences start to fall away, and the basic pursuit of the most enduring questions of who we are and why we’re here emerges. My hope is that, in watching the film, the viewer starts to feel that. Maybe it comes as a new idea, or maybe it’s a welcome old familiar one.

You have a very distinctive documentary style. It is poetic, sensual, and centered on interestingness. What are some of your favorite documentaries?

From pretty early on, I knew Between the Folds was going to be mostly about ideas. And I wanted the challenge of not working towards a narrative arc, but an arc around the evolution of thoughts. I’m already drawn to films like that. Sans Soleil, for example, by Chris Marker, who just died recently. It’s basically a meditation on memory, time, and place. And through a series of images and spoken ruminations, the viewer will end up sifting through thoughts and memories of their own. It transcends something specific. And everyone will see that film differently. I love that.

I love that film, like music, can go beyond the literal and sometimes reveal things that are

hard to articulate….ideas that are weakened when reduced to words. In this way, through pictures, film can speak to different viewers in different ways. That was challenging to me with Between the Folds — to be not teacherly about origami, but to use it as a metaphor. Since most people aren’t interested in origami, per se, it had to work on a different, more conceptual level.

What has the audience reaction to Between the Folds been like?

A lot of mail and email comes in from surprisingly different people – architects, designers, marine biologists, novelists, preachers, prisoners. It’s not because they love origami. I think it’s because, in our own ways, we all see a certain complexity in nature that’s often not acknowledged in our abbreviated, focused, and hyper-labeled lives. I think we all kind of go through life understanding things are more complicated and richer than that.

And I think the film has resonated with people because in this strange, simple art form you can catch a glimpse of that greater complexity. Origami invites us to think about that, and those are beautiful thoughts. But, even so, I never thought that making a film about such a niche subject matter would resonate so widely.

How long have you been doing origami yourself? Do you continue to do it?

It has only been a metaphor for me. I definitely tried it during the making of the film. I wanted to know what it was like to hold something so basic and elemental and have it transform in my hands into something else. But I’m not good at it. [Laughs] It’s hard! I mostly did geometric stuff, but recently I was taught by Michael LaFosse to fold Eric Joisel’s much loved Rat. It was really fun, and I could probably never do that again by myself.

How did you find all the fascinating characters in your documentary?

It’s a pretty small world. I have to say it was not so hard. They know each other. I met one of the mathematicians and he introduced me to one of the artists, and it just kind of took off like that.

Origami is a pretty collaborative art form where makers share discoveries. That’s part of why it’s accelerating so quickly. They’re all building on each other’s epiphanies. And because so many of them come to it with their own visions and reasons, the sharing doesn’t detract from the power of their own work.

Have you kept in touch with any of the characters? Where are they now?

I’m in touch with all them. They’re all doing great. They’re all busy doing what they do best. Still folding — they’ve absolutely found their passion and calling in life.

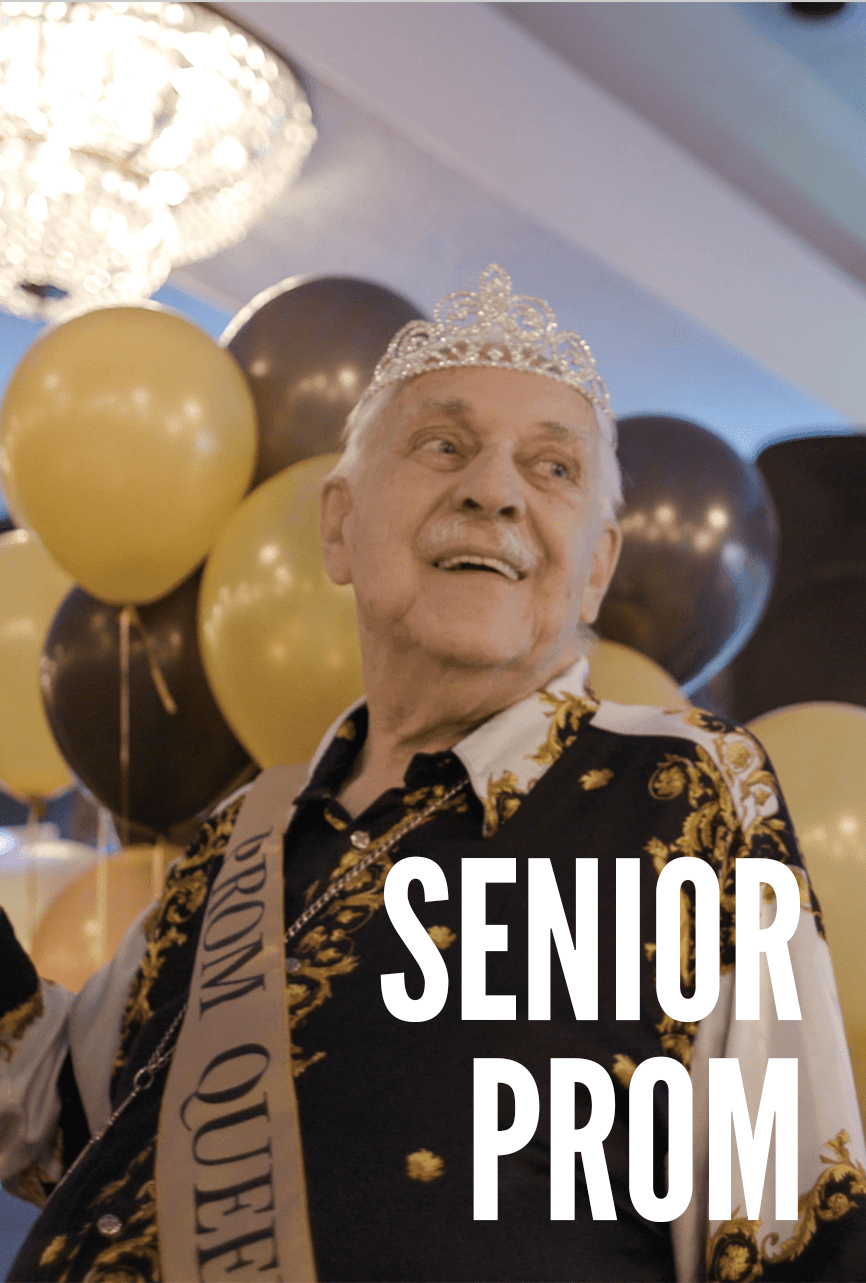

I’m sorry that Eric Joisel passed away in 2010. How did you react when you heard about his passing?

It was a dual experience, really. He had become a good friend, so I prepared as best I could for the loss of a friend. What I didn’t anticipate were the feelings that come with the early death of an artist. Ideas unfinished. Pieces frozen in time. Singular ambitions and thoughts gone with him. Everything just stopped. Of course, no one else can ever finish them.

Plus, he was a solitary person. I was afraid that all we knew and remembered of him would fade into the past. I wanted him to have some recognition – for him to be recognized publicly. And so I wrote to most of the English language newspapers around the world and informed them of his death. About a week later, to my surprise, the first and only paper that contacted me was The New York Times and they ran a beautiful obituary on him with photos of him and his work. It recognized the unique nature of his work. It logged him into the historic record. A good account of his life and work is now available. Recognition had mostly eluded him, and I can’t even begin to think how he’d feel if he had seen it.

Perhaps, not surprisingly, out of this experience came my next documentary project – a film about the obituary writers at The New York Times.

Why obituary writers?

The obit writers at The New York Times have a pretty unusual view on the world. Processing the data of so many unusual lives, they have an uncommon meta view of our culture and who we are, based on who we chose to remember. They have extraordinary knowledge of the people who have shaped the world around us. That invites an avalanche of interesting questions.

We’ve begun shooting, so we’re in early production. In the meantime, I’m working on a

television documentary series about climate change for Showtime called Years of Living

Dangerously. We’re shooting now and it will air next fall. It’s great. It’s nice to be able to be doing both.

How did the first IL broadcast of Between the Folds affect you or your career?

We had been on the festival circuit for a while. When you hear “documentary” and “origami,” no one gets that riveted. It was a small circle.

I’m eternally grateful to Lois [Vossen] for looking at it. Because of the PBS broadcasts,

millions of people have seen it now. It went on to get a Peabody. It gave me the courage to tackle subjects that can’t necessarily be reduced to a sound bite or a pitch. Films that, in fact, need the full hour to convey the complexities of their subjects. Everything is interesting if you look closely enough. And that’s the beauty of the documentary form — to be able to capture the beauty of so many things we might never otherwise see.