While HIV/AIDS is no longer a death sentence to the same extent it was 20 years ago, 50,000 Americans are diagnosed with HIV each year, and the disparities are startling when broken down by race, gender, and region. As reflected in June Cross’s film Wilhemina’s War, which puts a human face on the situation, the Southern United States is especially suffering.

According to Southern Aids Strategy, the South, which makes up 28 percent of the US population, accounted for 43% of new AIDS diagnoses in 2013 – the highest rate in the country. Nearly half of the deaths from HIV/AIDS from 2008-2013 took place in the region.

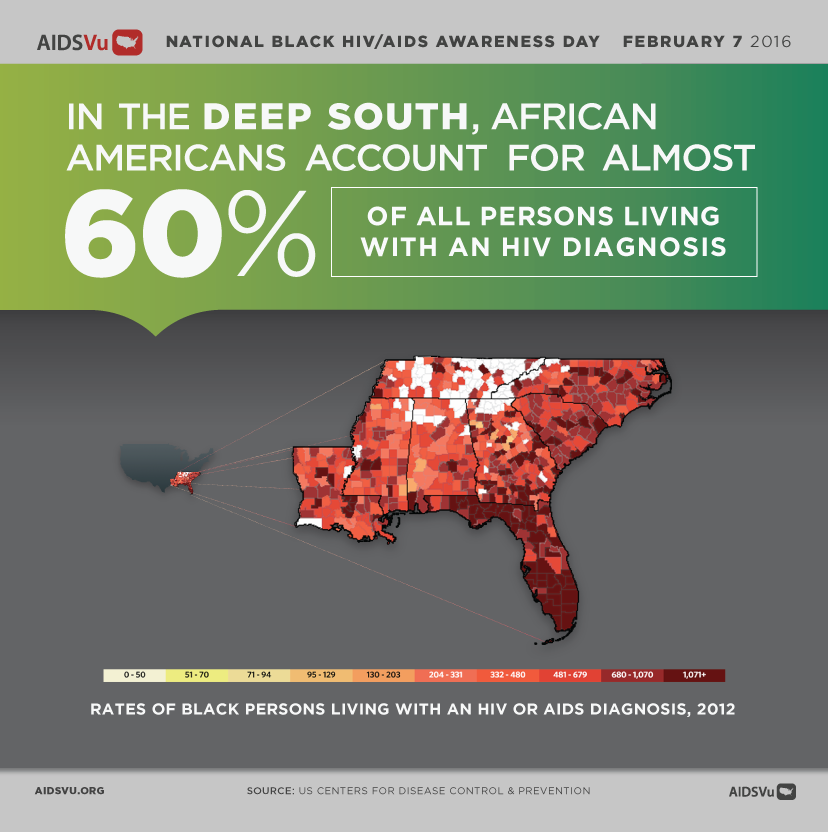

In 2014, 44 percent of estimated new HIV diagnoses in the US were among African Americans, who comprise just 12 percent of the US population. In the South, African Americans account for almost 60 percent of all people living with an HIV diagnosis.

The Prison Factor

HIV/AIDS among African Americans is an epidemic that can be traced to factors such as the prison industrial complex:

The injustices caused by racial profiling in law enforcement, and bias in criminal prosecution and sentencing, are now a subject of significant public attention… [T]he end result of these practices — the mass incarceration of nonwhite men – may also be fueling an urgent public health crisis among some of the most disadvantaged members of our society.

A study conducted by two professors of public policy at the University of California, Berkeley, determined that from 1970 to 2000, a period in which the incarceration rates for black men skyrocketed to roughly six times the rate for non-Hispanic white men, the H.I.V./AIDS infection rate for black women rose to 19 times the rate for non-Hispanic white women. Using various sources of data to investigate the connection between these developments, they concluded that “higher incarceration rates among black males explain the lion’s share of the black-white disparity in AIDS infection rates among both men and women.”

Not Just the South

HIV/AIDS disparities aren’t only confined to rural communities in the South. This 2015 story discusses an HIV outbreak in rural Indiana, where one town has a higher incidence of HIV than any country in sub-Saharan Africa, and draws links between the rising rate of infection, lack of healthcare access, and the slashing of government-funded public services:

Public health experts say rural places everywhere contain the raw ingredients that led to Austin’s tragedy. Many struggle with poverty, addiction and doctor shortages, and they lag behind urban areas in HIV-related funding, services and awareness… Like much of rural America, Austin has a dearth of medical providers. There’s only one doctor, and a Planned Parenthood clinic in the county that used to provide HIV testing and referrals closed in 2013 as government funding declined.

“The risk is real for many rural counties that now lack public health infrastructure,” says Patti Stauffer, vice president of public policy for Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky. “Where there is no public health safety net to educate people about how to stay healthy, and no one to make relationships with populations who are engaging in risky behaviors, the potential for health crisis exists.”

Politics and Healthcare

As seen in Wilhemina’s War, which follows Wilhemina Dixon as she cares for her daughter and teenage graddaughter, both living with HIV in rural South Carolina, Governor Nikki Haley’s rejection of billions of federal dollars through the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) and cutting of $3 million in AIDS prevention and drug assistance programs has resulted in substandard or nonexistent health services, medication, and medical care.

ACA (a.k.a. “Obamacare”) had the potential to extend healthcare coverage to millions of uninsured Americans, and states also had an option to expand Medicaid eligibility to cover more low-income adults. But politicians opposed to government intervention in healthcare voted against the Medicaid expansion – South Carolina is one of 19 states that rejected the expansion. As a result, hundreds of thousands of patients who fall below 100 percent of the poverty level did not qualify for any help. Johanna Haynes, the CEO of Careteam, which provides medical care and support for uninsured clients living with HIV in rural South Carolina, points out that “the poorest of the poor are the ones who pay full price for premiums… and have very high deductible[s].”

As the Washington Post discovered in 2014, Southern states have the least expansive Medicaid programs as well as the strictest eligibility requirements to qualify for assistance. The effects have been devastating:

None of the nine Deep South states with the highest rates of new HIV/AIDS diagnoses –Alabama, Georgia, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee and Texas – has opted to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. Those states also have the highest fatality rates from HIV in the country.

Federal spending policies have added to the problem. Most of the federal money for HIV treatment is distributed through the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency (CARE) Act. The original legislation carved out money for heavily impacted large urban areas. Now, however, smaller Southern communities are in need of help, and they are not eligible for those dollars.

Many of the people living with HIV/AIDS in the South are desperately poor. Many live in rural areas miles from a clinic — and they don’t have access to a car. Others have no running water, or even homes. A study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released last year found that more than 40 percent of those infected have an annual household income of $10,000 or less.

Federal Funding Disparities

According to Wilhemina’s War, the South has more people with HIV/AIDS than San Francisco and New York City combined, and South Carolina has the highest rate of rural people living with HIV/AIDS in the country. Yet South Carolina, which is sixth in the nation in the rate of AIDS, ranks 19th in the country for federal funding – receiving $7.9 million, in contrast to New York’s $80 million and California’s $70 million.

The South received 33 percent of federal AIDS/HIV funding distributed in the US, despite having 51 percent of all new HIV diagnoses in the country. New York and California, which had 19 percent of new HIV diagnoses, received a combined 36 percent of funding [source: Southern AIDS Strategy]. The South Carolina Rural Health Research Center reports that 91 percent of micropolitan rural and 98 percent of remote rural countries lack a Ryan White medical provider.

Unemployment, poverty, and slashed federal and state funding mean a lack of medical and educational resources for those who need it most. As Cassandra Lizaire writes:

[Wilhemina] Dixon’s travails in the South juxtapose with the resources I take for granted as a New Yorker. Here, opportunities for HIV testing are numerous: local clinics, STD testing centers, church outreach… In New York City, you’re a walk or a train ride away from support and care via public transportation. Without a car, travel is difficult in South Carolina. So whether someone goes to the doctor depends on medical need, but also access to a car and money for the fuel to get there.

Watch to Learn More