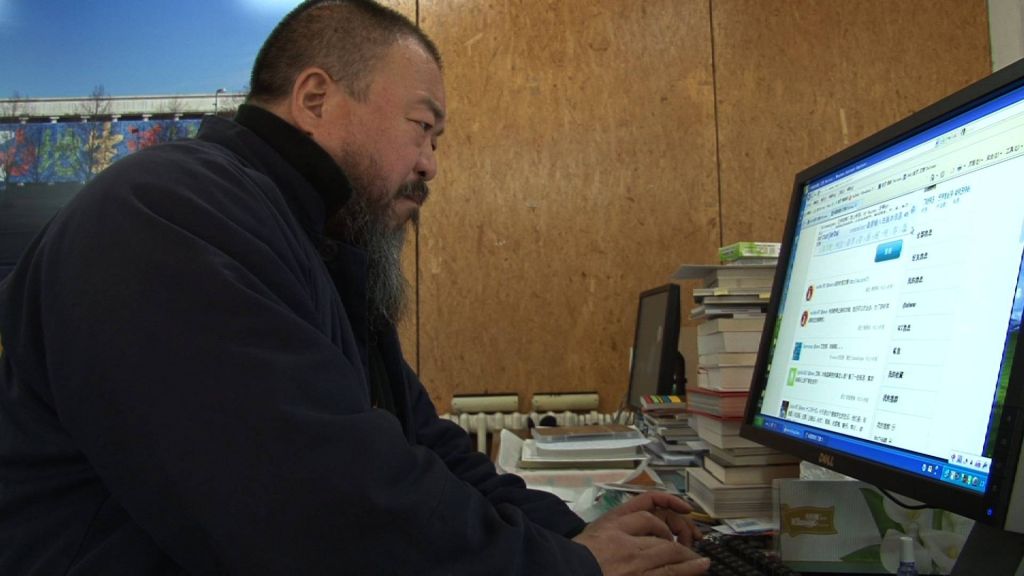

Ai Weiwei is a fearless Tweeter. In 140-character snippets, the gruff Chinese artist, activist, and the subject of Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry (airing Monday, Feb. 25, on Independent Lens) defends freedom of speech. Social media platforms are “like water and air, but in China we can’t even talk about it,” Ai Weiwei said at the Paley Center for Media in New York, according to the Los Angeles Times.

Despite China’s best attempts at censorship, Ai Weiwei’s online activism has organized thousands of volunteers, exposed the names of the more than 5,000 schoolchildren killed in a Sichuan earthquake, and blessed the Chinese government with ample photos of Ai Weiwei’s middle finger.

The blowback has been brutal. The artist had surgery in 2009 for a brain injury he claims was dealt by the government. He was jailed for three months in 2011 without charge. Ai Weiwei awaits the next retribution, but keeps faith in his confrontational digital activism.

“The internet is uncontrollable,” he said. “And if the internet is uncontrollable, freedom will win. It’s as simple as that.”

In spite of the dangers, Ai Weiwei has inspired others in China and abroad to take the charge through tweets, viral videos, and one of the largest social networks in China, Weibo. Here are some examples of their heroic digital activism.

Exposing Corruption

A Chinese migrant worker is missing $560,000 USD in unpaid wages. Instead of keeping her head down, she makes a viral video. Half parody, half protest, the video popularized last fall shows Miao Cuihua impersonating a Ministry of Foreign Affairs official who oozes bureaucratic jargon — and demands her back pay. The video has received more than 14,000 views.

In the video, Miao quotes a government official saying, according to Tea Leaf Nation: “I represent the government. If I tell you we’re not paying, then we’re not paying, what are you going to do?”

Other bouts of online activism have gotten government officials canned. Cai Bin, who formerly ran a Guangzhou urban management bureau, was fired last fall after social media users publicized the fact that he owns 22 homes.

He wasn’t the first to lose his post because of online protesters. Yang Dacai, former director of Shaanxi Work Safety Administration, was fired after Weibo users shared photos of him flaunting luxury watches. According to The Wall Street Journal, Yang is now known to the Weibo-sphere as Uncle House, and Cai Bin is known as Watch-Wearing Brother.

Environmental Truth-or-Dare

This February, an entrepreneur in the large city of Hangzhou offered 200,000 yuan ($32,000 USD) to the environmental protection bureau chief, Bao Zhenmin, if he swam for 20 minutes in the polluted river he oversees. On the social media site Weibo, the CEO posted pictures of the river clogged with trash from a nearby rubber factory, he claims. The dared bureau chief, Bao Zhenmin, acknowledged the pollution, but said it came from residents.

Around the same time, Weibo users in the Shandong province posted smartphone pictures of industrial waste and accused neighboring factories. The government took notice. That week, a Shandong environmental protection bureau offered a 100,000 yuan reward for details in a pollution investigation.

Other successes include national protests organized online in 2011 by more than 12,000 people that pressured officials into transferring a toxic paraxylene plant in Dalian.

“Environmental and food safety affects everyone. In China, even the most privileged people can’t live in a bubble,” Jeremy Goldkorn, director of Danwei, a China media research firm, told Bloomberg Businessweek. “With food safety and environmental issues, there is a little bit more room for people to make noise.”

Censorship

In response to these flurries of online activism, China has clamped down. The government announced in December it will require internet users to register with their real names. “When each Weibo post becomes tied to an identified person, then each individual user will be more likely to practice self-censorship with respect to their own posts,” said Nathan Green at Pando Daily.

In addition, the Chinese government has jailed dozens of social media users. Six microbloggers were arrested last spring and 16 websites shut down for “fabricating or disseminating online rumors.” The bloggers claimed the military was about to start a coup and that they saw tanks in Beijing.

The Great Firewall of China prevents remotely controversial or damaging messages from spreading. Propaganda officers use monitoring systems to catch phrases that might seem innocuous, but could spell an uprising, such as “Dalai Lama.”

“Some people say that for China internet is a gift from God,” wrote Su Yutong, a Chinese blogger living in Germany, for Amnesty International. “However, for internet users in China, it is more like dancing in shackles.”

Hacker University

Nevertheless, Ai Weiwei and others have found workarounds, and the hacker knowledge is spreading. A new international school is teaching online strategies to human rights activists. The school, run by the U.S.-based Robert Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights, is based in a former prison donated by the city of Florence. In addition to teaching organizations and businesses human rights legislation, it will train individuals on practical online skills, such as using software for anonymous internet access.

Chinese expats have also spearheaded online efforts by taking advantage of the relatively freer internet outside their homeland. In 2011, social media users in Brooklyn tried to spark the “Jasmine Revolution” in China, inspired by the Arab Spring. Many of the users and websites that called for a revolution were shut down, and dozens of people were arrested after February demonstrations.

Despite the “shackles” of Chinese censorship, social media users have accomplished many acts of defiance. They take the slack out of slacktivism. As Ai Weiwei said, “A small act is worth a million thoughts.”