Birth of a Movement, based on Dick Lehr’s book, captures the backdrop to a prescient clash between human rights, freedom of speech, and a changing media landscape — that happened in 1915. It is essentially the story of legendary film director D.W. Griffith, whose technically groundbreaking but inarguably racist silent film blockbuster Birth of a Nation was a hit that year, versus the Boston-based African American newspaper editor William M. Trotter who led protests against it. But it is also the story of much more: of racial stereotypes, of early embers of the Civil Rights Movement that would light up later, of telling alternative histories.

Filmmakers Bestor Cram (who’s been making documentaries since the 1980s, including Scarred Justice: The Orangeburg Massacre, Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison, and Circus Without Borders) and Susan Gray (whose films include Public Enemy, a documentary profiling four former members of the Black Panther Party, that was broadcast on Showtime) spoke to us about making a historical film that had massive resonance today, about getting people like Spike Lee, DJ Spooky and Henry Louis Gates involved, and on connecting the dots from William Trotter to Black Lives Matter.

[Responses here are from both Bestor and Susan collectively unless noted.]

Why did you want to make this film, tell this particular story?

Lack of representation and misrepresentation in film is not a new story. It’s a foundational issue that’s been at the forefront of Hollywood storytelling since its origins in the early 20th century. The Birth of a Nation, which was approaching its 100th anniversary when we began making this film, set an example for films to come, by exploiting dangerous stereotypes about African Americans and contributing to a culture in which blackness is a wrong that needs to be righted. While The Birth of a Nation maintained its status as Hollywood’s first blockbuster, the story of William Monroe Trotter and the fight against the film remains a largely untold story. As a crusader for Black civil rights in the early 20th century, Trotter is a landmark figure in American history who deserves his rightful due.

We wanted to examine the legacy of the Civil War, the memory of reconstruction history and how it has been falsely interpreted, the role of Hollywood, and in particular The Birth of a Nation, in contributing to that false narrative, the early struggle for equal rights in a post-slavery/racially segregated society, and that the fight by African Americans against the film ultimately led to the growth of the NAACP.

What surprised you the most as you dug into this story?

How was it that Trotter was lost to history while WEB Dubois and Booker T. Washington are historical characters who still appear in textbooks and are taught in schools today? Some experts have told us because [Trotter] was a radical, and history is not kind to radicals. Others have told us because he didn’t write as prolifically as DuBois who is remembered for his writing. Hopefully, this film will help change that.

What do you know about African American filmmaker responses to Griffith during that era, because there were some filmmakers who got their due only much later…

Immediately following the film’s release the NAACP tried to get their own film off the ground in response, but never got the funding together to make that happen. Five years later, independent African American filmmaker Oscar Micheaux responded with an answer film called Within Our Gates, which countered Griffith’s Birth of a Nation with a new set of characters showing who the real villains were and turning the film’s claims on its head. Instead of a black man trying to rape a white man, in this film a white man tries to rape what turns out to be his own daughter, and an entire family falsely accused is lynched. The film was censored and all copies disappeared until a copy was found decades later in a warehouse in Spain. Regardless, it was all too little, too late, the damage had been done: Birth of a Nation became arguably the most-watched American film with 200 million people having viewed it by 1930.

Do you remember your own first time seeing Birth of a Nation, and what was your reaction to it then?

Bestor: I couldn’t watch it all the way through.

Susan: I found the blackface confusing, and couldn’t tell who was supposed to be black or mulatto in the film. I was amazed at the blatantly racist images of the African Americans in the legislature and the KKK being the heroes who save the day by terrorizing black Americans into not voting at the end of the film. I also noted how masterfully the white supremacist views were conveyed through “innocent” storytelling, like the little kids playing with white sheets that gave protagonists the idea of the KKK robes — which the good women of the South then sewed for their men as an act of patriotism.

Do you think film classes should still show Birth of a Nation, and what context should teachers put around it when they teach it?

It should be studied as an important moment in film history and the evolution of the narrative film, both from a dramatic and a technical perspective. The context needs to frame the various currents of post-civil war reconstruction — segregation, abolition, women’s suffrage, white power, identity politics, and representation issues, recognizing that the film was an important event in social history as it ushered in the role of cinema as propaganda, the use of hate speech and raised questions about where censorship plays a role in our society. It can also be framed in this current era of “alternate facts.”

It could also be taught in conjunction with Triumph of the Will, made by Hitler’s filmmaker [Leni Riefenstahl], another film that introduced groundbreaking filmmaking techniques but was also propaganda that glorified the Aryan nation.

How did you approach trying to make this story vital and relevant to today’s younger audiences? How do you think it relates to current-day racial tensions, and to movements like Black Lives Matter?

We included the voices of some of today’s top African American filmmakers — Spike Lee, Reginald Hudlin, DJ Spooky, and had them explain how Birth of a Nation had impacted them personally and their work. We began making a film about the end of America’s first Reconstruction, and during the course of making the film the Trayvon Martin shooting happened, Black Lives Matter was born, George Zimmerman who shot Martin was found not guilty on all counts, the Supreme Court ruling on Shelby County vs Holder gutted the Civil Rights Act, we witnessed police shootings and choking black men to death captured on cell phones by bystanders, the #OscarsSoWhite controversy, and Nate Parker’s Birth of a Nation. With the election of Donald Trump supported by the so-called alt-right, this became a film about the end of the second American Reconstruction and its contemporary relevance became clear without having to make it obvious to anyone young or old.

Do you think D.W. Griffith learned from some of the angry reaction to Birth of a Nation, or did he remain defiant and unchanged?

Bestor: His feelings were always based on the freedom of the artist and he would argue that he was not a racist. I don’t think he acted defiantly, but rather empowered to tell stories.

Susan: At the end of his life he did say he didn’t think the film should be shown to young people. Clearly, he had evolved in his understanding of why the film was offensive to African Americans and exacerbated racial hatred.

[Read more about Griffith’s follow-up work after Birth of a Nation]

What were some of the challenges you faced in putting Birth of a Movement together?

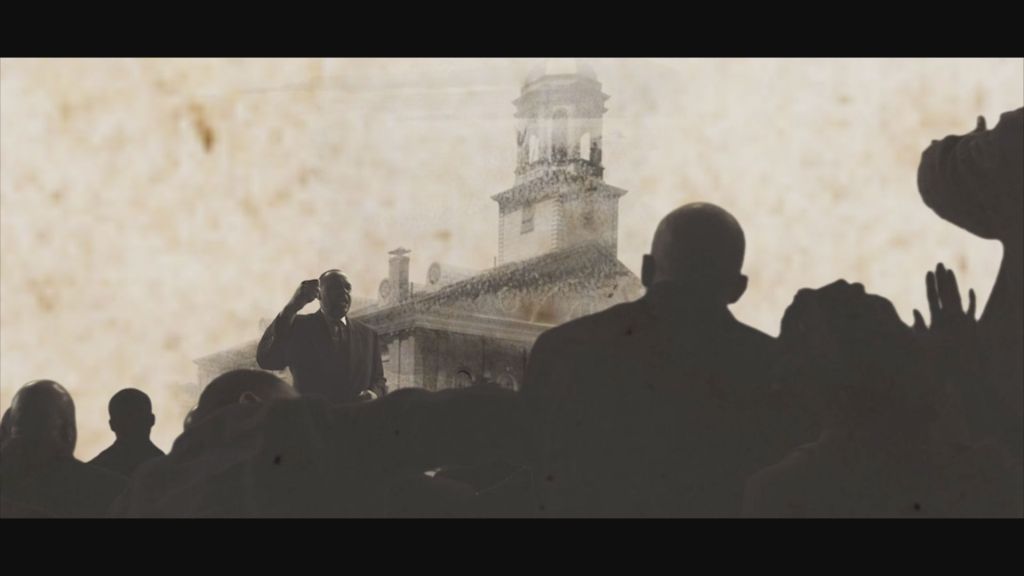

Putting together the right team, people with experience and expertise on both the civil rights and the filmmaking stories. And figuring out a way to bring William Monroe Trotter to life without having an actor acting out his life. There are very few photographs of Trotter or surviving and we didn’t want to have someone else who wasn’t William Monroe Trotter, represent him. So we chose a very impressionistic way of doing recreations combined with computer graphics.

How were you able to get such (presumably busy) luminaries like the aforementioned Spike Lee and DJ Spooky to participate in the film? Obviously, the subject means a great deal to them, but can you talk about how you approached them to be in your film?

Bestor: Sam Pollard, our executive producer, teaches with Spike Lee at NYU and Spike made his first film The Answer as a response to Birth, so he was a natural to participate. And DJ Spooky had already done a soundtrack for his own version of Birth before working with us so he was a natural as well.

Susan: We were surprised how many of the people we wanted to include in the film had their own early experiences with Birth of a Nation, and how much it had impacted their work. Quentin Tarantino made Django Unchained as a reaction to Birth of a Nation, but it was Reginald Hudlin, the film producer, who inspired him to make that film. Reggie tells us about the first time he saw [Birth] at Harvard, a story we only learned about doing his interview for the film. He agreed to do an interview through our writer Kwyn Bader, who knows him.

What are your three favorite/most influential documentaries or feature films?

- My Brother’s Keeper (Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky)

- Family (Sami Saif)

- The PBS documentary series Frontline

What film/project(s) are you working on next?

Fix Democracy First with [Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist] Hedrick Smith: a look at grassroots reforms in democracy, like gerrymander reform, top two primaries, public financing of campaigns and dark money reform, that are taking root across the country.