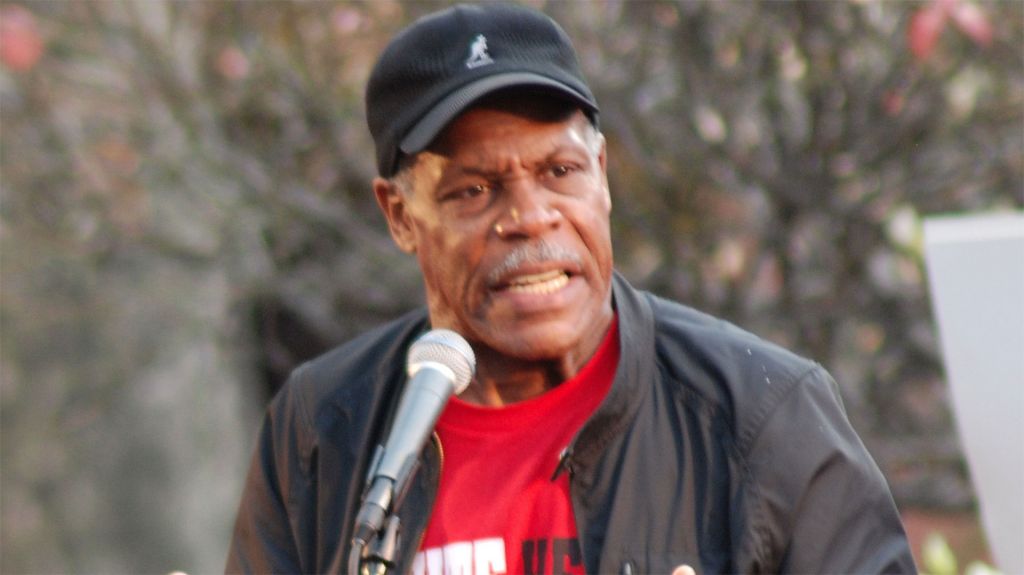

Our friends over at The Progressive Magazine have generously allowed us to share their interview with Danny Glover, who co-produced The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975. The film makes its television debut on Thursday, Feb. 9 at 10 PM on Independent Lens.

By Ed Rampell

Many movie fans know Danny Glover as an actor from the Lethal Weapon series, but this Hollywood action star is also a serious intellectual, activist, and producer of thought-provoking documentaries and features. The UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador and Amnesty International USA Lifetime Achievement Award recipient is putting his political consciousness and filmmaking know-how to good use as the CEO and co-founder of New York-based Louverture Films, a production company named after Toussaint Louverture, the leader of Haiti’s revolution.

Glover’s new project as co-producer is The Black Power Mixtape 1967–1975. He is also now appearing in the new TV series Touch.

Glover has participated in the Occupy Wall Street movement, declaring in a speech at an October 8 Occupy L.A. rally: “This is our Earth,” he said. “This is our common ground. This is where we stand. And this is where the fight begins.” He urged each protester to be a “24/7 warrior.” And had harsh words for President Obama. “We have to say to that administration in Washington, D.C., that its job plan is inadequate; it doesn’t solve the problem. It doesn’t do anything but create false hope,” he said. “We’re tired of false hope.”

In this candid interview, Glover reveals himself to be a deep thinker and a politically engaged artist.

Ed Rampell: What do you think of movies about black struggles such as To Kill a Mockingbird, Mississippi Burning, Cry Freedom, and The Help, where white characters are the protagonists? How is The Black Power Mixtape different?

Danny Glover: Well, The Black Power Mixtape is a documentary, first of all. It brings us closer to the voices we heard at that particular point in time. I doubt that any of those films you mentioned expanded the dialogue about the period itself. In The Black Power Mixtape, you hear the voice of Angela Davis — not someone playing Angela Davis.

Remember, we’re talking about 1967, the year before King’s assassination. We’re talking about the emergence of Black Power, which is a discussion King mentioned in his last book, Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? We’re talking about the meaning of Black Power and the possibility that it alienated our supporters, both white and black.

The civil rights movement didn’t deal with the issue of political disenfranchisement in the Northern cities. It didn’t deal with the issues that were happening in Northern cities like Detroit, where there was a deep process of deindustrialization going on. So you have this response of angry young people, with a war going on in Vietnam, a poverty program that was insufficient, and police brutality.

All these things gave rise to the Black Power Movement. It’s a misconception to believe that the resistance ended with the civil rights movement. The Black Power Movement was not a separation from the civil rights movement, but a continuum of this whole process of democratization.

Q: You were in college in the Bay Area at that time.

Glover: I was a member of the Black Student Union, part of the central committee at San Francisco State University. During the 1968 strike there, I was certainly very much involved in the activities that occurred on campus. It was part of an extraordinary period in my life. The strike and its outcome had an enormous impact on the system of education and on our lives as well. The strike began as a response to the college’s refusal to hire Professor Nathan Hare [the so-called “father of Black Studies”], and certainly unified the college around issues of justice. These issues were reflected in many communities: the Asian American community, Hispanic community, Native American community. So it brought us together with teachers and also with progressive whites. All of us came from diverse backgrounds, but at the same time the reasons why we were at San Francisco State University in the late 1960s was because of the agitation and movement building that had occurred within our communities. We saw ourselves not separate from the community but intimately connected to the community.

Q: What are some highlights of your political involvement over the years?

Glover: I was involved with the anti-apartheid movement through my work as an artist and also through my political commitment. My theatrical background was in the great work of the South African playwright Athol Fugard.

Q: Wasn’t one of the Lethal Weapon movies really an anti-apartheid film?

Glover: Lethal Weapon 2 used the platform to talk about the apartheid system. That was a very important moment for us.

Q: What do you think of President Obama?

Glover: President Obama is a man who had certain advantages because of the civil rights movement. He had the opportunity to go to some of the best schools in this country — schools that train you how to run the political paradigm, not challenge it. The leaders of the Black Power Movement were challenging that paradigm.

Q: Do you think Obama’s done enough for the black community?

Glover: I’m not here to talk about the black community, particularly; I’m here to talk about the world community. Mother Earth is in pain and ailing — bglobal warming. The world is dealing with issues of immigration, deindustrialization, and poverty. When I was born 65 years ago, there were 2.5 billion people living on the whole planet. Now there are 2.5 billion people living on less than $2 a day. That’s the kind of reality we have to deal with.

How Obama deals with that is certainly a question we all have to grapple with. But what’s more important is that we talk about movements; change happens through movements. The movement to end slavery, the movement to bring justice for those who have been left out of the system, movements to include women, movements around sexual preference — all these movements brought about change.

Q: Cornel West said: “Barack Obama is the black mascot of the Wall Street oligarchs.” What do you think about West and Tavis Smiley’s criticism of Obama, and the hostile reaction they got in the black community?

Glover: Democracy is about criticism. I didn’t elect Obama because he’s a black; I voted for Obama because he was the right person at the time. Period. The exceptionalism of a black U.S. President is not important to me. It’s what he does. And who he has at the table. And what he does to change the world — that’s what’s important.

Q: Why do you think there aren’t more revolts by the unemployed?

Glover: Because we live in a climate of fear, and because of this whole ideology of consumption almost to the point of religion. Whether it’s the consumption of entertainment or the consumption around buying things, we’re so caught up in the idea around our appetites that we don’t have a clear distinction about what we need and what we just want. Plus, the decline of trade unions is a factor. When you have powerful unions, you have a working class that is politicized.

Also, there is a lack of leadership outside the Beltway, outside of politics. I remember when Langston Hughes used to write a column around this character for 25 years published in black newspapers: Jesse B. Semple. He always used that as a voice, sometimes in comic ways, of having everyday people’s voice come through this common folk hero, who was an ordinary working guy. He would talk about anything from police brutality to the Korean War. Those kinds of expression and identification are no longer prevalent in our popular culture. Popular literature and culture used to reflect people’s aspirations, pain, and passion. All those particular things are no longer available to us.

Q: Besides The Black Power Mixtape, what other documentaries and features is Louverture Films producing?

Glover: We’re trying to tell stories. We’re a company that’s concerned with global change and the effect of global cinema. We’re not simply tied to the very limiting framework of U.S. filmmaking. Some of the most amazing stories are happening on the global scene. My extraordinary producing partner, Joslyn Barnes, she’s just virtually changed my life, with the way she constructed this company, and how we go about telling the stories we want to tell.

Q: What is the status of your Toussaint Louverture film?

Glover: My Toussaint film is in limbo. We still hope after all this time that we can find another way to get this film done. Hopefully, there will come a point where the advantages outweigh the obstacles. The main obstacle, of course, is money.

But there are things that make me excited about what I’m doing: Trouble the Water [the 2010 documentary Glover executive produced] on New Orleans, or something like [the 2009 documentary Glover executive produced] Soundtrack for a Revolution, about the power of the music of the civil rights movement. Or [the 2006 feature Glover executive produced and acted in] Bamako, about the African debt crisis, a platform to discuss the experience of people who actually live it. All of these are important ways we can use film as a forum inviting people into a dialogue. Art is about the dynamics of the human experience. How we do that in terms of this company has been one of the exciting moments of my career.

Q: OK. How do you feel about your former Lethal Weapon co-star’s anti-Semitic outburst, his substance abuse problems, his alleged violence?

Glover: Mel Gibson is my friend. I love Mel. He’s not the person that I hear people are often trying to diminish. Whatever his challenges are in life, he still remains someone I’m very close to.

Q: What do you think of the screen image today of blacks in America?

Glover: Just look at the cinema itself: It’s comprised of lots of movies about graphic novels, and if you’re not 20 years old and wearing a cape and a mask and white, you’re out of business. Today’s cinema is a proliferation of comedies, which are in some ways creating caricature images. They’re one-dimensional. I don’t like looking at African Americans within that context. Hollywood is designed to check the box office on Monday morning and see: “How’d we do? How much?” It’s another facet of this whole culture of accumulation and consumption. Black people are caught up in it, white people are caught up in it, white actors, black actors, female actresses — everybody’s caught up in it.

But I have the capacity to express what I feel needs to be expressed. And that’s it. I try to do what I believe in.

L.A.-based film historian/critic Ed Rampell is the author of Progressive Hollywood, A People’s Film History of the United States, a co-founder of HollywoodProgressive.com, and co-founder of the James Agee Cinema Circle, an international group of critics who annually award the Progies for Best Progressive Films and Filmmakers.