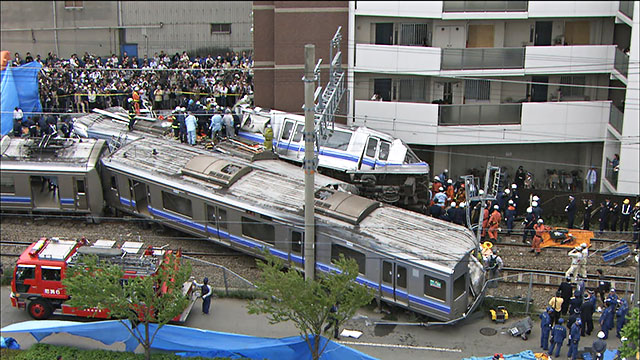

Filmmaker Kyoko Miyake was born and raised in Japan, though she has lived in the UK for the last 12 years, in addition to a year-long stint in Paris. So she’s lived in multiple places where trains and public transportation are an integral part of daily life and culture. Her film Brakeless looks at one very specific tragic accident in Japan — the 2005 Amagasaki railway crash — as a way to ignite a larger discussion on the value of (and obsession with) efficiency in our lives.

What was your own experience growing up in Japan taking trains? Do you have positive memories of the train system?

I spent a lot of time commuting in Japan. I remember being a high school student (it took me 2.5 hours to get to school) and commuting among salarymen, thinking, “these guys look SO exhausted.”

I have also spoken to many people who have had a similar moment when they were young, thinking, “oh I don’t want to become like those salarymen,” but a few years later, they find themselves having become them. The Japanese commuting scene is often an object of derision from Western tourists but for many Japanese, it provides moments of self-reflection, like “what am I doing with my life, commuting like this every day?”

I also remember people being quite aggressive when the train was delayed. Sometimes they just shout randomly, and quite often at the station attendants.

How is the train system different in Europe and do you find yourself impatient with it?

After I moved to Britain, for about a year or so, I was very often upset because nothing seemed punctual. You are lucky if your train ever arrives on time! But after a while, I realized that I was the only person at the train station huffing and puffing in anger when the train was delayed. Everyone around didn’t seem to mind that much. I learned to be patient and realized how much I took for granted while living in Japan. I also learned to deal with it when things don’t happen exactly as planned and to always allow for a margin of error in planning. It’s a bit scary to think that in Japan, I was living a life that cannot accommodate a one-minute delay. When this accident happened in 2005 and when I watched the news on BBC, I felt somehow that I knew something like this was going to happen in Japan sooner or later.

What were some of the biggest challenges you faced in making Brakeless?

Researching was quite difficult as I was a complete outsider. People in the region speak with quite a distinct accent and I knew that the moment I opened my mouth, they knew I was not local. At the beginning, I was quite weary and could also tell that they put on a “standard” Japanese accent when they spoke to me. Towards the end of filming, they started to have a heavier accent which made me happy (although that might mean having to subtitle some of them in Japanese).

How did you gain the trust of the subjects in your film, some of whom were survivors of the crash?

By listening to them and asking them to share their thoughts. In a way, it helped me that more than eight years had passed since the accident when I started my research. The victims were worried that the accident and their loved ones might be forgotten as time went by. So there was more space for an outsider like me.

They seemed to also appreciate that I came in as a “blank slate” not being aware of the “politics” around the accident – who has a bigger say, whose opinion is maybe more authentic, etc. If you are based in the area, you get fully engulfed in those politics.

I became quite close to some of the characters in Brakeless. One of them – the artist with the can – said to me about half a year after we met, “Kyoko, you have become quite boring these days. You started to sound like just another Japanese journalist. I don’t know any more why I am talking to you. When you first came to meet me, you were completely ignorant about the accident, but at least you had a lot of quite crazy ideas and strange questions that intrigued me. Now you might know more about the accident, but so do the local journalists. What’s the point of you coming all the way from London and doing this film?” This was a wake up call for me, and I realized that I was too desperate to be included in that community surrounding the accident. I started to show off my newly acquired knowledge, and I had stopped asking questions that came naturally.

What has been the reaction in Japan to the film, if people have seen it yet? Do you think things have indeed changed for the better there since the accident or is it still “a work in progress”?

The reaction has been very good. It meant a lot to me when our contributors – both those who appear in the film and those who don’t – appreciated the film, saying that I listened to their stories.

Unfortunately, not much has changed in terms of attitudes towards efficiency and punctuality. The faster and quicker things get, the busier we seem to get – rather than winning some free time from the technological advancement.

What are your three favorite films?

My Architect, White Ribbon, The Hunt.

What advice do you have for aspiring filmmakers?

Don’t wait until someone gives you a chance some day. Create your own chance. Be realistic and know your marketability.

What film project are you working on now or next?

I’m developing a film called Tokyo Girls which is about Japanese pop idols. I want to explore what it means to grow up as a girl in a society that infantilizes women and is obsessed with young female sexuality.