In one short but memorable scene in the documentary Soul Food Junkies (premiering on Independent Lens Jan. 14), filmmaker Byron Hurt interviews a woman who just can’t find decent, healthy food in her neighborhood. She gives a local market an earful when she repeatedly sees vegetables “that look like they’re having a nervous breakdown. I tell them ‘How dare you do this? How dare you put this out in this community?’ ” she says.

Sonia Sanchez is not alone in her desire for better quality food and the inability to find it nearby. Like millions of other Americans, Sanchez lives in a food desert — a low-income community with little or no access to a supermarket or grocery store. Fresh fruits, vegetables, and meat can feel like a far-off mirage, so residents of food deserts tend to get their food at ubiquitous fast-food restaurants and corner stores. It’s no surprise that food desert residents tend to have high levels of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases.

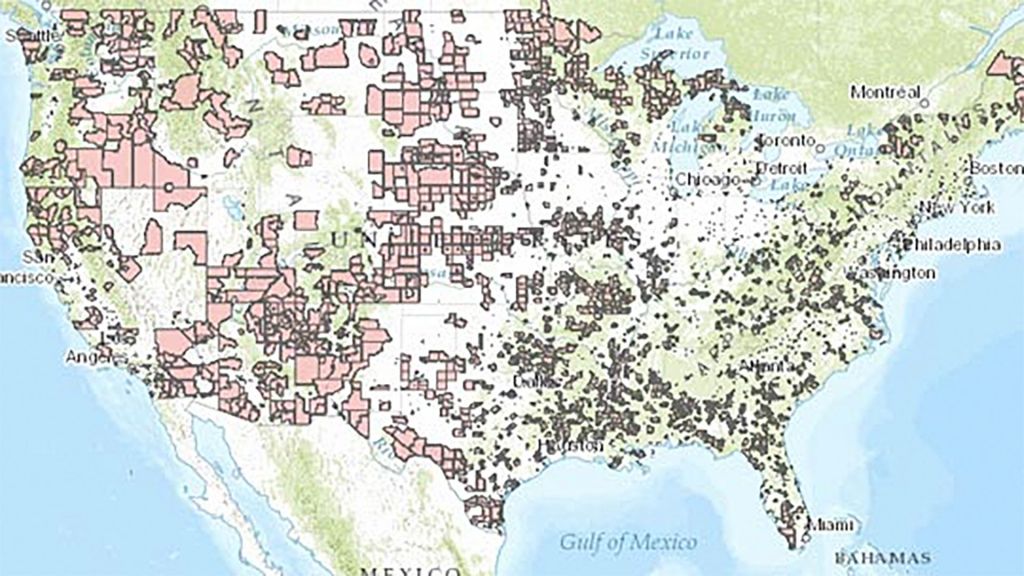

According to the USDA, about 10 percent of the 65,000 census tracts in the United States meet the definition of a food desert. Some 13.5 million people live in these food deserts, with the majority of this population—82 percent—living in urban areas.

The USDA has an excellent food desert locator map online tool that will give you a better idea of where food deserts are, and census information about the areas. You can even find population characteristics about each tract within a food desert.

As you see in the map above, food deserts dot the country. In some places, they paint it in wide swaths. Sometimes they’re in areas where you’d least expect them to be. In fact, not far from the Independent Lens office in our tourist-haven, world-class city of San Francisco, we’ve got a couple of pretty significant food deserts. NewsOne ranks San Francisco No. 6 on its list of the worst urban food deserts in the United States.

Food deserts often exist in the shadows of great cities. The bountiful oases of grocery stories piled with fresh produce can be relatively close to food deserts, yet completely out of reach for many.

It’s a cruel irony. But this proximity also brings potential solutions: Cities are helping create urban gardens in empty lots, cultivating an appetite for healthy food and the empowerment of growing it. Food-desert neighborhoods are creating space for farmers’ markets. And grocers from other neighborhoods are starting to bring their bounties into food deserts. Pop-up groceries — where local grocers bring buses or trucks filled with fresh and healthy food into low-income neighborhoods — have been a hit wherever they’ve launched.

The idea is that if healthy choices are available, people will buy them. And that works to an extent. But old habits die hard. A 15-year longitudinal study found that upping the number of grocery stores in low-income areas didn’t result in people automatically buying healthier food.

“Just because you build it, doesn’t mean you will change people’s behavior,” study author Barry Popkin, a professor of public health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said in a Time magazine article. “Price, quality, accessibility, incentives, they matter too. Every community is different, but new efforts or supplementing existing infrastructure works if they’re accompanied with affordable prices, education, promotion or community collaboration.”

Will Allen, founder of Growing Power, a Milwaukee-based national nonprofit that supports easy access to safe and healthy foods, says the transition from a lifetime of unhealthy food can be a challenge. “Once people get into that mold of eating bad food, their first taste of really good food tastes strange,” he says in Soul Food Junkies. He believes education is paramount if palates are going to change.

Food deserts aren’t going away any time soon. But with community efforts, education, pop-up markets, accessible farmers’ markets, community gardens, more grocery stores, a better scenario is more than a mirage. “The kids are passing on the word to their parents and other adults in the community,” says Allen. “To me, this is a multicultural, multigenerational revolution.”

Soul Food Junkies filmmaker Hurt is hopeful that his film will be part of this revolution.

“I hope this film makes it easier for families and communities to talk openly and honestly about the impact food has on their lives and their health,” he recently told Independent Lens. “I also hope this film will be used widely as a discussion starter in communities of color around food consumption, health, wellness, and fitness.”