Missing in Brooks County is an eye-opening investigation set in an unforgiving region of South Texas, where migrants go missing more than anywhere else in the United States. The documentary features activist detective Eddie Canales of the South Texas Human Rights Center, who helps search for the missing on behalf of anxious families, along with forensic scientists.

The film’s co-directors and producers, Jeff Bemiss and Lisa Molomot, were on their individual paths as accomplished filmmakers before collaborating on Missing in Brooks County. Bemiss, whose film The Book and the Rose was shortlisted for the Oscar for best short film, also shot and directed the touching and joyful short doc Coaching Colburn, about a young man born with Fragile X Syndrome who doesn’t let it get him down. Molomot’s first documentary, the potent and inspiring The Hill, aired on PBS’s America Reframed, and she’s directed several documentaries about the American Southwest. They came together to make Missing in Brooks County, a Critics Choice Documentary Award nominee that FilmThreat called “exceptionally effective.” Adds The Boston Globe, it is “one of the most nuanced and disturbing…films about the immigration crisis.”

I spoke to the pair—Bemiss is based in Connecticut and Molmot is based in Arizona—about why they wanted to tell this gripping but harrowing story, how they were able to get different perspectives, and whether they’ve been able to get the documentary in front of politicians.

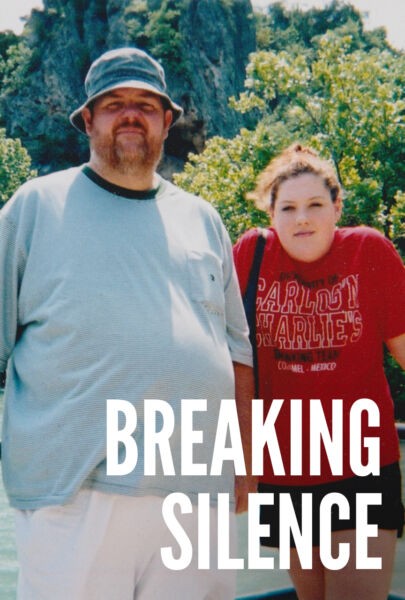

Filmmakers Lisa Molomot and Jeff Bemiss

This film feels like a detective story in a way: Eddie and Dr. Kate Spradley and some of the other researchers are all investigating these disturbing, missing person mysteries, and viewers don’t know exactly how it will turn out in each case (though it’s made clear that the prognosis is bleak). Was that how you approached it?

On our various filming trips to Brooks County over the four years, we would show up for a week or two and film whatever was happening. It was almost impossible to plan anything, as whenever we tried to make plans, people would decline and instead tell us to call them when we arrived in town. So, needless to say, we had very little control over filming—at the beginning, at least.

Once we developed a trust with the community in Brooks and particularly Eddie Canales, we were able to film him as he worked, rather than just getting a bunch of interviews. We began to focus on his relationship with Dr. Spradley and all the work they did together. And that’s when we began to see their work as almost detective-like.

Forensic scientist Dr. Kate Spradley

So how were you able to get closer to and gain the trust of everyone who shared their stories with you?

Jeff Bemiss: We made 15 trips to Texas, usually for two weeks at a time. Michael Vickers and his Texas Border Volunteers were somewhat friendly to media, but also somewhat suspicious. It took us three years to get invited on one of their night operations. Eddie and Kate, the humanitarian volunteers, were more approachable, though I’m not sure they understood the scale of what Lisa and I were after. Eddie used to complain, “There’s nothing these two don’t want to film.”

But that’s how the trust grew. The more time we spent with each other, the more it felt like we were telling a story together. We weren’t collaborators. We were co-conspirators.

Eddie Canales and South Texas Human Rights Center team along with Brooks County Sheriff’s Deputy Don White at center right

On that topic, to keep the perspectives balanced in the documentary, you include more conservative ranchers and those Border Volunteers you mention who basically “hunt” for migrants. How did you get them to be included, and did they have any interesting reactions to seeing the film? Do you feel their perspective might ever change?

We don’t know if Mike Vickers and his Texas Border Volunteers have watched the film. Mike’s worldview is fairly entrenched, and he shares it in the film. He doesn’t distinguish between the criminal smugglers and the decent people they are smuggling, people who just want to join the U.S. workforce alongside their families and friends.

What were some other big challenges you faced in making Missing in Brooks County?

Jeff Bemiss: Getting an accurate count of how many people have gone missing since the start of the “Prevention Through Deterrence” border policy [first introduced in a document entitled “Border Patrol Strategic Plan of 1994 and Beyond”] was one of our biggest challenges. We didn’t want to repeat the same official Border Patrol number, which is a massive undercount. To move the conversation forward, we spoke with experts, including a large-scale mortality specialist, to get projections.

We settled on the number 20,000, which we have been told is still very conservative.

Given that tragic number, how did you even begin to focus down on which cases to follow for the film? Was it working with Eddie that led you to more specific cases, or access to family members, or how did you choose?

We originally followed the stories of a couple of families who we met through Dr. Kate Spradley and her NGO Operation Identification; however, we ultimately decided to focus on the two families in the film. The first [one] we met through Eddie at the South Texas Human Rights Center on one of our filming trips. Moises, the cousin of Juan Maceda, was meeting with Eddie when we popped into the center one day, and we knew instantly that this was a story to follow as Juan was still missing.

The main story of our film is that of Homero Roman. We met the Romans after they reached out to us via the “contact us” button on our website. They came across it when Googling “missing brooks county.” We met with them at a Starbucks in Houston, and shortly after we all decided to collaborate on telling their story.

As you’ve screened the film, have you gotten any specific feedback from audiences that surprised you, or were revelatory? Anyone share any epiphanies?

Regardless of people’s feelings about immigration, they tend to appreciate the film’s 360-degree view. After one screening in Brooks County, a local rancher stood up and apologized to Eddie Canales. The rancher said he had been suspicious of Eddie and against his efforts. After seeing the film, he told Eddie he now understands him.

Eddie Canales scrubs graffiti

Are there any plans to screen Missing in Brooks County for either Federal government bodies or state politicians?

We shared the film with leaders at the Department of Homeland Security across the country in November and hope to work with this group on getting the film seen more widely by border patrol agents. Additionally, through our partners at the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) and the Southern Border Communities Coalition (SBCC) in Washington, D.C., we are in communication with various congressional staffers to potentially host a congressional screening this coming March.

Was there anything you filmed that couldn’t make the final cut of Missing in Brooks County but is worth people knowing about?

Jeff Bemiss: We filmed with a woman whose sister was exhumed in Brooks County, but she couldn’t attend the funeral. She herself was trapped in what is called the Golden Cage, the area north of the border, but south of the checkpoint. Her story portrayed another harmful effect of U.S. border policy which essentially encages people. Unfortunately, we already had multiple narratives to weave together, and had to let her story go.

What’s something from the film that audiences so far have asked you the most about?

Jeff Bemiss: Audiences tend to ask about the checkpoint shown in the film. To be clear, it is not near the border—it’s an interior checkpoint 70 miles north of the border. There are over 100 across the U.S., and two-thirds of the country lives inside a checkpoint zone.

These checkpoints exist due to a Supreme Court ruling from the 1970s [United States v. Martinez-Fuerte (1976)] that has had all kinds of unintended consequences, including causing many deaths as you see in the film. Nonetheless, the ruling has never been reexamined.

Can you tell us anything new that’s happened with the people featured in Missing in Brooks County since the filming stopped?

Lisa Molomot: The Romans continue to search for Homero with the help of Eddie Canales. Eddie is hoping to buy the building where the Center is currently located so he can renovate it and pass it along to the next director of the South Texas Human Rights Center when he retires. Dr. Kate Spradley is focusing more on advocacy these days and has passed along her lab duties to her colleague at Texas State University.

And what’s one thing that you hope PBS audiences will take away as a discussion point with friends and family after watching the film?

We made Missing in Brooks County because we felt that if people could meet the families of the missing and hear their stories, especially our political leaders, they would feel differently about the policies we are creating for our border. If someone is moved by the film, they absolutely must call their political representatives and tell them how they feel. Any policy that causes over 1,000 deaths a year needs to be examined.