This piece is part of an ongoing Independent Lens series exploring documentary film history. Stay tuned for more installments.

Since the dawn of cinema, cameras have been taken around the world to capture unique and exotic sights previously available to audiences only in still photographs.

Motion picture pioneers the Lumiere brothers sent their cameras to get scenic shots of foreign landscapes and cultures, and rivals (such as Britain’s Mitchell and Kenyon) followed suit, creating programs that took audiences to faraway places. Mitchell and Kenyon narrated their presentations, turning the shows into events, while on the lecture circuit, explorers started using movie cameras to supplement their slide shows with moving picture footage.

These pre-documentary forays inspired filmmakers and explorers to take their cameras into more remote and inhospitable locations.

Herbert Ponting accompanied Captain Robert Scott on his 1911 expedition to the Antarctic with two moving picture cameras. Frank Hurley, the official photographer of Ernest Shackleton’s 1914 Antarctic expedition, also brought a movie camera. Captain John Noel, gripped by fascination with the Himalayas, documented the third British ascent of Everest in 1924. Photographer and anthropologist Edward S. Curtis went to the coast of British Columbia to recreate the lost culture of the Pacific Northwest tribes. Robert Flaherty, still celebrated as the father of documentary filmmaking, took his cameras to the Arctic to capture the culture of the Inuit, and to Samoa to document South Seas life. And before they made King Kong, Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack hauled their cameras through the mountains and plains of Iraq and the jungles of Thailand to explore the rigors of life in worlds far from our own.

What they and other filmmakers had in common was a drive to bring their cameras to locations not yet documented, let alone visited by westerners, and to capture events previously recorded only in books and diaries and, sometimes, still photographs. They were adventurers and explorers in their own right. At their worst, they exploited their subjects, exoticizing and exploiting them with a patronizing air. At their best, they provided invaluable anthropological records and eyewitness accounts of historic events. And together they pioneered a unique (and short-lived) genre of documentary and quasi-documentary filmmaking at the dawn of filmmaking: real-life adventure cinema.

In the Land of the Headhunters

Edward S. Curtis’ In the Land of the Headhunters (1914) isn’t a documentary by definition but it is an invaluable document of a culture preserved through ritual over the centuries. Curtis worked with the Kwakwaka’wakw (Kwakiutl) people of British Columbia to recreate life from before the arrival of white settlers. While he wrote a melodramatic tale drawn as much (if not more) from western mythology and European fairy tales as from native cultures, he worked with the tribe to recreate the costumes, masks, canoes, and longhouses of the old culture, preserving a legacy that the Canadian government was trying to stamp out (the tribes were forbidden from practicing their cultural rituals and this film provided an exception, which they eagerly took).

In this way, it anticipates Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North, which staged recreated scenes to show a way of life that was no longer being practiced by the Inuit people. The storytelling in Headhunters is rudimentary but the imagery is often gorgeous, with Curtis’s photographer’s eye capturing dramatic images set against striking coast landscapes and seascapes.

The film was orphaned for decades and until recently only existed in an incomplete version (titled In the Land of the War Canoes) reconstructed in 1973 from existing prints and set to a naturalistic soundtrack of native music, chants, and sounds. In 2008, the original cut was reconstructed with newly-discovered footage and still images (to cover footage missing or damaged-beyond-reclamation), using and set to the original score composed for the 1914 debut. In addition to preserving that initial presentation, surviving copies of the sheet music with notations made by musicians helped in the reconstruction of the original cut. In 1999, it was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress.

Nanook of the North

Nanook of the North (1922) is considered the first great nonfiction film and filmmaker Robert Flaherty the godfather of documentary filmmaking, even though the film is not a true documentary by contemporary standards. Flaherty had every intention of documenting traditional life among the Inuit people of the Arctic Circle but discovered that the culture he wanted to show no longer existed. So, with the help of Nanook and his friends and family, Flaherty undertook the mission of re-creating a lost Eskimo culture in a series of staged scenes. Nanook ice fishes, harpoons a walrus, catches a seal, traps, builds an igloo, and trades pelts at a trading post, all captured by Flaherty’s inquisitive camera.

These were not actors miming action in dramatic, theatrical poses in a studio but real people in the snow and ice hunting real animals. Patience and determination were necessary attributes to get this kind of footage. Flaherty shot it on the northeastern shore of Hudson Bay, hundreds of miles from the nearest railway line, with a cast of locals. He lived with them and set up a makeshift lab to develop his film on location. He even showed some of the footage to the actors.

Nanook was actually Flaherty’s second attempt at a documentary on Inuit life — he accidentally burned the negative of his first production — and he applied lessons learned from that original shoot when he went back north with his cameras. He decided to focus on a single family and build his narrative around their survival over the course of a year. As with Curtis, his intentions and efforts were honorable. “I am not going to make films about what the white man has made of primitive peoples,” Flaherty wrote. “What I want to show is the former majesty and character of these people, while it is still possible — before the white man has destroyed not only their character, but the people as well.”

Though he presents a “happy” culture bordering on primitive innocence (Nanook and his family were in reality quite westernized), his loving portrait is anything but condescending, and ultimately Flaherty shares his tremendous respect and awe for an ancient but evolving culture.

On a purely visual level the film is a beautiful work of cinema, an understated drama in an austere, unblemished landscape of snow and ice. With unerring simplicity and directness, Flaherty recreates the details and rhythms of a culture long gone. It may seem naïve by modern standards yet it remains moving, involving, and quite beautiful. It was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress in 1989, one of the first of 25 films to be so honored as “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

South / The Epic of Everest

In contrast to these reconstructions, South and The Epic of Everest are straightforward documentary presentations of real-life adventures. Their pleasures are not in narrative or storytelling, but in the images and events captured in locations heretofore unseen by anyone but a few intrepid explorers.

South (1919), shot by Frank Hurley during the ill-fated 1915 Shackleton Expedition to the Antarctic, is short of narrative drive and dramatic structure but filled with indelible images. Hurley didn’t construct stories around the men or try to turn them into “characters” in a drama. He simply recorded the daily routines, the desert of the ice that their ship, the Endurance, cuts through to reach landfall, and the ordeal of being stranded when the ship is trapped in the ice.

At its best, the record of the ship trapped in the ice, momentarily free after two days straight of ice cutting, and finally crushed by the piling ice flows, the film is more dramatic than any modern special effects set piece. Making it more poignant and powerful: it was shot by a cameraman who was well aware he was stranded at the South Pole without a radio, miles from the ocean and equipped with only three small boats to get them 800 miles to civilization (which, naturally, they have to drag across unstable ice flows to even get to the wet).

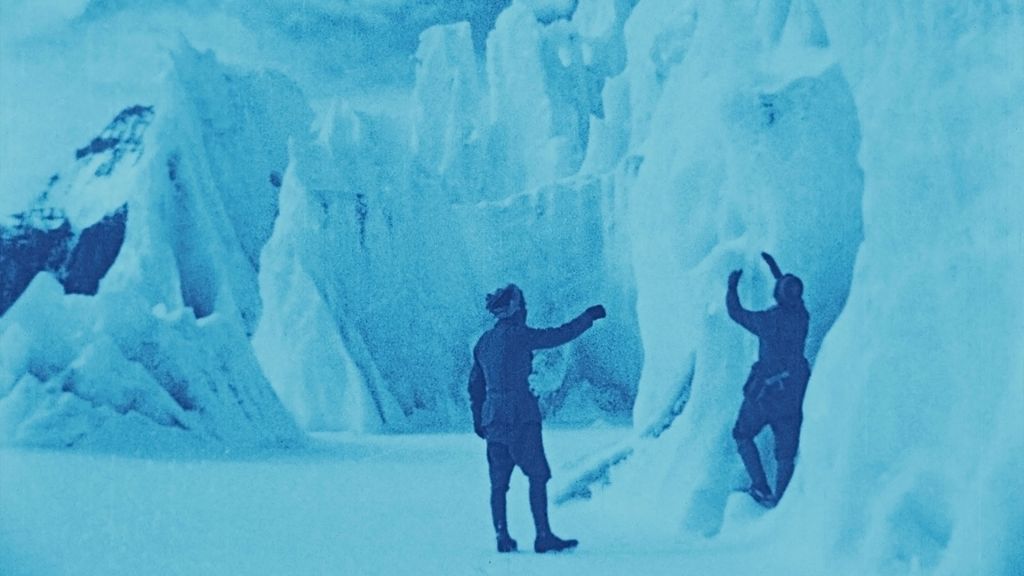

The Epic of Everest (1924), the film record of the third British ascent of Everest, is presented with a solemnity befitting the gravity of the event (two of the greatest and most celebrated climbers of the day, George Mallory and Andrew Irvine, died trying to reach the peak). It’s also as beautiful a nonfiction film you’ll see from the era. Captain John Noel hauled a hand-cranked camera (developed specifically for the challenge of shooting in the snow and ice) along with the expedition party (of 500 men and animals, according to the titles) and captured truly astounding images.

He brought state-of-the-art telephoto lenses which enabled him to get viable images from as far away as two miles. But he also brought art and aesthetics to his shots, many of them like landscape portraits alive with passing clouds, shifting shadows, and halos of snow and mist whipped up by the winds. They are framed beautifully and use the light and shadow as dramatic elements.

A lot of documentaries of the silent era leaned on staged scenes and dramatic recreations and called upon their subjects to play the part rather than simply be. There are no such narrative contrivances here. Noel picks dramatic vantage points with which to observe the expedition party — most of the shots are from afar, placing the men against the majesty of the mountain peak or the dangers of the immediate challenge — and photographs the camp as if recording the details for the historical record. And in addition to chronicling the expedition, he presents the earliest film footage of traditional Tibetan people living in the mountains, a light ethnographic introduction to this culture that was, in 1924, still all but cut off from world.

The film was unavailable for years, with elements in the BFI film vault waiting to be resurrected; the restoration was completed and unveiled in 2011.

The two approaches – reflected in In the Land of the Headhunters and Nanook of the North on one side, and in South and The Epic of Everest on the other – became the two foundations on which subsequent non-fiction filmmaking was built: the cinematic anthropologist, and the adventure documentarian. But they also became the foundation for a new kind of filmmaking I like to call “exotic adventure cinema,” a genre that flourished for a brief period between the final years of the silent era and the early years of the talkies.

Exotic Adventure Cinema

Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack took these two strands of non-fiction filmmaking — the cinematic anthropologist and the adventure documentarian — and applied the style and the spectacle to their own brand of filmmaking, giving birth to what I think of as exotic adventure cinema.

Their first production, Grass (1925), followed the migration of tribesman over the rugged, icy mountains to the fertile plains of Iran. It is a remarkable piece of documentary but was never completed to their satisfaction, and Paramount cut their edit down even further. With that experience under their belts, with their next film they set out to tell a story and capture wildlife spectacle as well as document a culture.

For Chang (1927), the filmmakers took their cameras to the wilds of Thailand and captured sights that still have the power to awe audiences. They built the story around one family’s struggle to survive in the jungle and carefully cast their family from the most photogenic locals they could find. The usual condescending attitude toward tribal peoples runs rampant through the film (“We be mighty hunters, Kru,” comments one warrior in an intertitle, as if their own language is but some pidgin dialect), and the filmmakers fill the loose story with goofy comic relief and a veritable petting zoo of furry little pups and cubs. But they also presented riveting scenes of hunters building deadfalls and spring traps, a leopard charging through the woods, and a tremendous herd of elephants fording a river like a rampaging army. They captured footage of wild tigers (one of which they ensnared in a trap, the better to get startling close-ups) and created an elephant stampede that levels a village, a sequence they concocted and executed with the help of the King’s private herd. Chang was honored with a nomination in the very first Academy Awards, one of three films nominated for “Artistic Quality of Production” in the first and only year of that category. It lost to F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise.

In the final years of the silent era, the Hollywood studios took over from the independents and dropped the often sincere portraits and dynamic spectacles into melodramas, love stories, adventures, and other familiar commercial genres. The studios sent their filmmaking teams to the far reaches of civilization to shoot on location, taking in the natural landscapes and wildlife, with the local population recruited to play background and, sometimes, even major roles, but in service to conventional stories that had little to do with the cultures they presented.

White Shadows in the South Seas

MGM recruited Robert Flaherty (Nanook) to helm their foray into tropical exoticism, White Shadows in the South Seas (1928). Flaherty had made Moana (1926) on location in Samoa and MGM wanted him to recapture that mix of location authenticity and idealized primitive innocence for their production, which was to shoot in Tahiti. To hedge their bets they sent their own man, cowboy picture director W.S. Van Dyke, as an “associate director” to handle the dramatic scenes and keep the production under control. The collaboration was short lived and Van Dyke soon took over completely (Flaherty simply couldn’t adapt his approach to the Hollywood timetable and left in frustration), working with islanders taking roles in a script concocted in Hollywood (rewritten substantially from the novel by Frederick O’Brien).

Shot almost entirely on location, with the actors (leading man Monte Blue, Raquel Torres as the island princess, Robert Anderson as the ugly American trader) and crew imported from Hollywood and equipment far more sophisticated than that available to the independent adventure filmmakers, it (somewhat ironically) tells a story of paradise corrupted by the infiltration of the white man and commercial exploitation, and tells it quite effectively. Some of Flaherty’s footage made it into the film, notably scenes of village life, but the studio men provided even more impressive scenes shot in the jungles and superb underwater shots of the natives diving for pearls. And the “documentary” aspect allowed the filmmaker to get away with topless shots of the native women, something that would otherwise never get past censors. The film won the Academy Award for Best Cinematography in 1930.

Made at the end of the silent era and released with a synchronized music and effects soundtrack (preserved on the Warner Archives DVD release), White Shadows in the South Seas was the first of four such films that Van Dyke made for MGM. He became their house specialist for location filming and exotica. He returned to Tahiti for The Pagan (1929), another South Seas melodrama of naïve and generous natives in paradise, this one with Ramon Novarro as the guileless native “pagan” and Donald Crisp as the white Christian businessman who hides his lust and avarice for the lovely native girls behind the Bible and looks down on all natives and half-castes.

Then Van Dyke was off to Africa for Trader Horn (1931), a great white hunter drama based on the dubious memoirs of one Alfred Aloysius “Trader” Horn and starring Harry Carey as the white trader in the African interior. All attempts at ethnographic authenticity are discarded in this adventure spectacle, which revolves around Horn and his protégé, Peru (Duncan Renaldo, soon to become TV’s The Cisco Kid) searching for the daughter of a missionary captured in a tribal raid and taking the now grown young woman (Edwina Booth) back to civilization while tribal warriors pursue them, intent on getting their blond goddess back.

Dialogue scenes and other sequences were shot back on the studio lot, where sound recording could be better controlled, but a tremendous amount of impressive safari footage was shot (without sound) on location. The opening act is a veritable nature documentary: shot after shot of the wildlife on the veldt with Carey’s Horn providing commentary, identifying each new creature to his partner (and the audience) with a little zoological trivia.

But it is also the wellspring of all the Great White Hunter, dangerous dark continent, and savage African tribe conventions and stereotypes that dehumanized every African and otherwise “uncivilized” character in a Hollywood movie for decades. This is an outlier in the documentary discussion, important for its location shooting and its influence on Hollywood adventure dramas for years to come, but in no way a legitimate representation of any kind of reality, and it has aged poorly. It was, however, a massive hit and an Oscar nominee for Best Picture.

Now firmly established as MGM’s adventure cinema specialist, Van Dyke made Tarzan (1932) without ever leaving the U.S., with Florida providing jungle locations and the rest shot on the studio lot against sets and rear projection (with stock footage cribbed from his own Trader Horn), and then moved into plum assignments such as the star-studded Manhattan Melodrama and the suave cocktail-hour mystery The Thin Man, all made in the comfortable studio. But he did strike out for one more adventure drama shot on location in the inhospitable elements, and it is remarkable.

Eskimo

The film, based on the books by Danish explorer and anthropologist Peter Freuchen [here are some fun side notes on Freuchen, Ed.], is a mix of documentary footage of hunts and village life (some of it likely staged for the camera, just like Nanook of the North), fictional scenes filmed on location, and recreations shot on studio sets and against rear projection. It’s also remarkably frank for 1934 about the sexual mores in the Inuit culture and the rape of an Inuit wife by a visiting trader. The film is both respectful and patronizing in its presentation of the native peoples and the performances are stiff and simplistic (for the white and Inuit actors alike) but the location scenes are impressive and there is a respect for the culture which, if oversimplified, is better than Hollywood’s usual stereotypes of native life.

Eskimo is genuinely involving in its own right but it is even more interesting as an anthropological artifact, a piece of cultural history, and as one of Hollywood’s last forays for years into on-location exotic adventure cinema. It would be a long time before the studios sent entire companies that far from the comforts (not to mention the infrastructure) of what Hollywood considered civilization.

Decline of the Authentic Location

With the advent of rear-projection techniques and sophisticated special effects, filmmakers stopped hauling their crews all over the world and started recreating exotic locations in the studio or in more hospitable locales. As silent movie historian Kevin Brownlow put it in The War, The West, and Wilderness, “Backgrounds became the most artificial parts of a film, instead of the most authentic.” The world was shrinking, sound recording added an additional challenge to location shooting, and it was easier on the stars to keep them close to the studio.

King Vidor’s Bird of Paradise, a South Seas melodrama shot in part in Hawaii, eventually returned home and recreated its tropical paradise on Catalina Island. Even Cooper and Schoedsack, the great adventure cinema independents of their day, gave up travel to build their greatest and most exotic adventure in the studio with sets, special effects, and the most charismatic puppet to become a movie star: King Kong (1933).

That’s not to say filmmakers gave up exploring. Hollywood simply left it to the independents, the iconoclasts, and the adventures who first excited filmgoers with their visions of the world unseen.

Editor’s note: Many of these films are available to stream or download, as well as rent on DVD. (They may also be free on YouTube, although we can’t vouch for the quality or the legality of those versions.)

Milestone Films has quite a few of these classic adventure documentaries, including In the Land of the Headhunters; Grass; Chang; and South.

Warner Archive offers all four W.S. Van Dyke films: White Shadows in the South Seas; The Pagan; Trader Horn; Eskimo. The Epic of Everest is available as an import DVD + Blu-Ray via the BFI at retailers like Amazon. Nanook of the North is available on DVD and Blu via Flicker Alley.

Sean Axmaker is a Seattle film critic and writer. His work appears in Parallax View, Turner Classic Movies online, Keyframe, and he writes a weekly newspaper column on streaming video, which you can find at www.streamondemandathome.com.