What led you to make this film at this point in time?

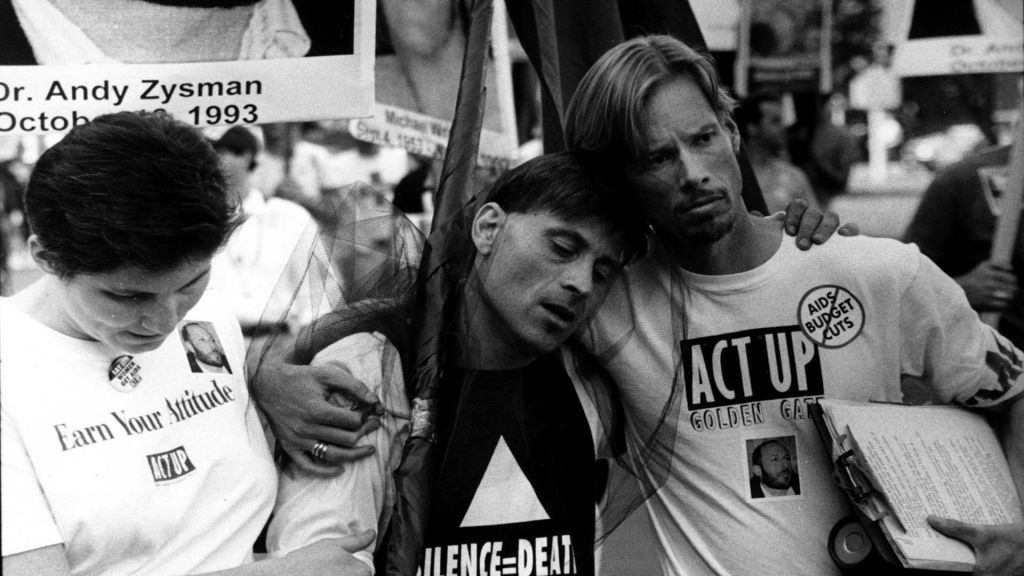

A younger boyfriend who had heard me speak many times about my experiences living in San Francisco during the AIDS epidemic suggested that I make a film. I realized that there hadn’t yet been a film that explored the enormity of that history in a reflective way, and felt that it should be done by someone who had actually lived through it.

What impact do you hope We Were Here will have?

I hope that We Were Here offers a cathartic validation for the generation that suffered through, and responded to, the onset of AIDS; that it opens a window of understanding to those who have only the vaguest notions of what transpired in those years; and that it provides insight into what society could, and should, offer its citizens in the way of medical care, social services, and community support.

What challenges did you face in making the film?

We Were Here attempts to evoke an epic history through the voices of only five people, and accompanying archival material. Because of the enormity of the subject matter, my choice was to try to evoke a sense of time, place, and circumstance from a very human vantage point, rather than to attempt an encyclopedic factual history. The biggest challenge there is that the history itself needs to be adequately documented, the opportunity is to capture the human experience in a way that a simply informational film can’t adequately do.

Who do you think this film will most resonate with?

We Were Here, though it deals with how a specific historical experience played out in a particular city, speaks to basic human experiences that transcend the AIDS story itself. It speaks to how individuals, and how a community, responded to an unimaginable crisis. This is something that almost everyone will face at some point in their life, in one form or another. But more specifically, the film certainly will speak to the generation that was most directly affected by the onset of AIDS, and the current generation – particularly of young gay men – who remain at high risk, and know little of the history of AIDS, and how we got to where we are today.

How did you gain the trust of the subjects in your film?

I selected interviewees who were emotionally open and deeply thoughtful. The fact that I’d also lived through many of the same experiences allowed for a very deep conversation which I don’t think would have been possible if the interviewer was looking in as an outsider. Also my cinematographer Marsha Kahm and sound recordist Lauretta Molitor also lived through those years, and helped create a safe and compassionate environment for the interviewees.

What would you have liked to include in your film that didn’t make the cut?

I’m sure if I looked back at the original interviews there would be plenty that I’d wish were still in the film. And there are certainly countless aspects of this complex history that the film isn’t able to address in 90 minutes. But I feel we were very successful in using creating an epic sense of history in a very intimate, personal way, which is exactly what I wanted to do.

Tell us about a scene in the film that especially moved or resonated with you.

Oh, there are so many … There’s a section in the pre-AIDS part of the film where Paul Boneberg is talking about a 1979 rally on Castro Street for Harvey Milk’s birthday the night after the White Night Riots. There are some beautiful photos of the crowd by Danny Nicoletta, and as the camera pans across the faces, Paul says, “We had no way of knowing that already AIDS was among us, probably 10 percent of the men in that crowd were already infected…” That section always makes me cry.

What has the audience response been so far?

What’s been most gratifying for me is that across the board, audiences and critics are expressing surprise that ultimately the film isn’t depressing, that it’s hugely inspiring and filled with love and compassion. For the interviewees, it’s been hugely validating to gain perspective on who they were in those years, who they’ve become because of their experiences.

The independent film business is tough. What keeps you motivated?

I’m not always motivated – sometimes I dread getting inspired because the process is so daunting. But like all doc makers, I can get overtaken by the sense that there’s a story that MUST be told, that if I don’t tell it maybe no one else will … and that I’m the right person to tell that particular story.

Why did you choose to present your film on public television?

It’s the perfect venue – freely accessible to anyone, presented without commercial interruption, and with integrity.