By Ivonne Spinoza

Brother is an intimate portrayal of addiction that makes us question our preconceptions and helps shed light on what really goes on inside the mind of a person suffering through this process.

I spoke with filmmaker Joanna Rudnick to go behind the scenes of this deeply personal, poignant story that she decided to share in a unique way.

How did the idea of making this a film come to you? What made you decide to share such a personal story?

Joanna Rudnick: I saw an opening to spend more time with my brother in a period of relative recovery and wanted to understand the myriad of factors that led to his addiction. At first, I wasn’t thinking about a film as much as just recording our conversations for my family. But once we started talking, I realized his story was universal to many who struggle with addiction and to families like ours.

I wouldn’t have moved forward with the film had Matt, my brother, not been 100% on board that he was ready to share his story, as there can be real ramifications still in talking so openly about opioid use disorders.

And how did you decide the right way to tell this story was through animation and phone conversations?

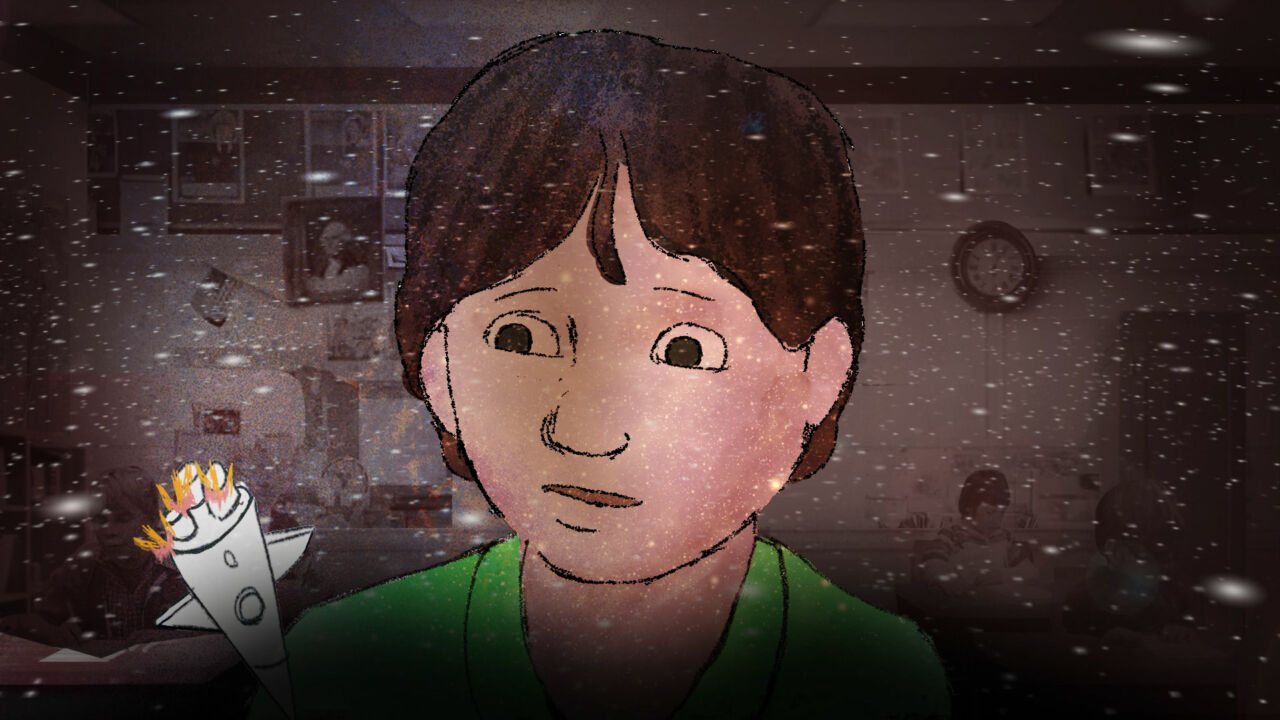

Joanna: I think we carry around a lot of implicit bias in this country towards people who use drugs. I felt that by using animation, we could reduce some of that judgment and allow audiences to tap into empathy. Addiction films can be voyeuristic and the animated world can remove some of that intrusion and avoid the traditional tropes of those stories.

Additionally, I wanted to appeal to a younger audience that craves more experiential and immersive storytelling and may have been turned off by a more traditional depiction of drug use. Finally, the animated world allowed me to move more freely between past and present and to blur those lines, as well as imagine and represent the internal states of addiction.

So the phone call was a very intentional creative choice.

Joanna: Yes. The telephone call represents the distance between us. You see the two of us in our own worlds represented as two living spaces in the proscenium of a theater, but as time goes on, we move closer together until we meet in a liminal space where the phone is gone. This is a metaphor for how with time, I could better understand Matt’s world and even inhabit it.

What was the biggest challenge you faced while making this film?

Joanna: Matt died from a fentanyl overdose before we had filmed the live-action sequences for animation. We had to find an actor who was able to inhabit Matt’s being and who could fully represent his mannerisms and emotions. We were incredibly lucky that our Director of Animation Andrew Lyndon had a relationship with Lance Barber, a phenomenal actor who agreed to play Matt in the film.

What was it like to hear your brother again through someone else’s physicality?

Joanna: What you hear is actually my brother’s voice and Lance mouthing the words Matt said in our calls. It was strange at first to see Lance as a physical representation of Matt, but he studied him so closely down to the way Matt would pull his t-shirt away from his chest or pace around the room when he spoke on the phone, that we knew he was meant to do this.

I loved the part that mentions other animals getting addicted, too. Was that really part of your original conversations or did you add/expand it?

Joanna: That was Matt’s way of making sense of addiction in a language he could understand. Matt was always fascinated by science as we see in the cosmos opening scene. He loved nature shows. This was part of our original conversation and felt so true to his individual experience and his very being.

The only way we expanded it was the archival montage we used to illustrate the action of our midbrain. We wanted to show we are a society that has accepted many addictions, such as shopping, gambling, alcohol, plastic surgery, exercise, etc., but stigmatize and criminalize addiction to certain substances. We are all trying to feed our hungry ghosts.

What do you think is the biggest misconception people have about drugs, addiction, and recovery?

Joanna: I think people can feel that drug addiction is a moral failing rather than a brain disorder. They think it can be “cured” with 30 days of rehab when it is a chronic disease that requires an ongoing combination of medicine and psychotherapy for most people.

Addiction doesn’t happen in a vacuum as we sometimes oversimplify. Instead, it is rooted in adverse childhood experiences and deep societal forces, such as racism and poverty. This means that to truly help someone recover, we need to give them reasons to live and also a real way out.

These wrap-around services are sometimes missing in modern-day treatment. I also know that most people cannot stop using opioids without Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT), so we need to make it readily available while ending the stigma around its use.

WATCH BROTHER

What’s your hope for Brother? What would you like to accomplish with this film?

Joanna: I hope the film helps families better understand and support loved ones going through addiction. I was fed a great deal of harmful, non-scientific advice about how to treat my brother, which has filled me with deep regret. I saw firsthand that tough love and coerced rehab don’t work, and that there is no process of recovery until that individual is ready and supported. I believe strongly in harm reduction and in trying to keep people who use drugs alive so that we can help them find a recovery path that works for them.

I also hope people walk away feeling like Matt could be their sibling, friend, or son and realize that even though he died, he wanted to live. As a mother who lost her son told me when I was making the film, “People always ask why the addiction, when I think the better question is why so much pain?”