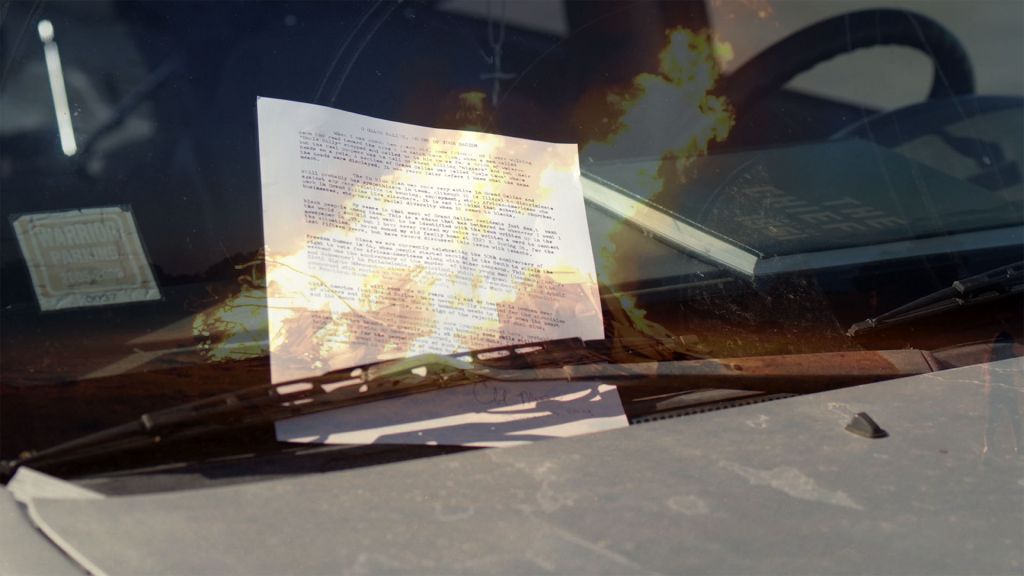

Joel Fendelman’s Man on Fire, which has its television premiere on Independent Lens, won the David L. Wolper Student documentary award at the 2017 IDA Awards. The story at its heart is shocking. In 2014, a 79-year-old white Methodist minister named Charles Moore drove to an empty parking lot in his old hometown of Grand Saline, Texas, and set himself on fire. He left a note explaining this act was his final protest against the virulent racism of the community and his country at large. It left the community reeling and looking for answers. The film explores this from current and former residents, all with different points of view on what happened and why. It provides no easy answers, but as Fendelman says, simply by asking the question of why, important conversations can be had.

In Reel Spirituality, Andrew Neel wrote: “the mere existence of this excellent film furthers his message and hope for healing and racial reconciliation.” It is, adds Christopher Bourne, an “illuminating, thought-provoking tale that illustrates one of the many tragic consequences of America’s failure to fully come to terms with, and to truly confront, the racism of its past, present, and its foreseeable future.”

Here’s our own conversation with the filmmaker.

Why did you make this film?

I was attending the University of Texas, Austin as a grad student in film. I was looking for a thesis film idea and a mutual friend connected me with my producer James Chase Sanchez. He is from the town of Grand Saline and was doing his dissertation about the town (he got his Ph.D. in racial rhetorics) and the incident of an elder white preacher self-immolating there in 2014 to bring attention to the town’s racism. I was immediately awe-struck by this preacher’s sacrifice and felt this need to learn more and explore how, if at all, this incident affected the town.

Who do you hope your film impacts the most? And what kinds of conversations do you hope come out of it? (Since this film is definitely a conversation-starter.)

I hope people of all races and nationalities are impacted by this film. Most of all, I want white people, both younger and older, to have a conversation on race, the history of slavery, and the contemporary impacts of segregation.

How did you get people to talk to you about what was obviously a sensitive subject?

The biggest challenge in making this film was trying to get people to talk on camera to us. The town of Grand Saline was quite sensitive about their racist reputation so it was difficult to open that can of worms. Many times we were stood up for interviews or it would take a number of times to convince someone to talk. It helped a lot that James was from Grand Saline. He was able to reference his grandfather who was a pastor in a nearby town and use his football playing days as ways to get people comfortable with doing an interview.

It also helped that one person spoke to us and saw that we had sincere intentions and told others that they could trust us. With that said, there was definitely an internal struggle within the town behind closed doors on whether people should trust us.

And how did you get the locals to trust you?

In addition to my producer being from the town, I find Texans to be quite upfront people and if you are direct and honest they will respect that. We tried to be transparent and direct with all our subjects. Everyone we interviewed we believe had a positive experience and left feeling like they were interviewed with respect. I think all of this helped contribute to building a trust with our subjects. The hardest part was getting them to talk; once that happened, everything fell into place.

What are some interesting things you had to cut out?

We thought if this was more of a biography of Moore that we might include more on his past protests in Austin, especially his multiple week hunger strike against the Methodist church, but this did not fit into our narrative. We also had more research on the history of self-immolation, but we did not think this fit in our story because it was more of a biography on Grand Saline and Moore, rather than just Moore himself.

Do you have a scene in your film that is especially a favorite or made the most impact on you?

Towards the end of the film, we interviewed an African-American pastor who preached at the large Baptist Church in Grand Saline for one year. I went in with expectations that he would have had a very difficult time in town, but the opposite was true. In fact, he shares a story on camera on how a white congregant came to him with remorseful tears in his eyes because of his former racist attitude. The pastor then forgives him because of the “love in his heart.” Every time I watch that interview, I get butterflies in my stomach. It shows the power of forgiveness and what’s possible.

Could you talk a little about the “Poletown” stories discussed in the film, and how that reflects the town’s history? [Poletown is an area of Grand Saline that supposedly derives its name from being a place where black men and women had been hanged from a lynching pole.]

In the making of this film, James Chase Sanchez and I went back and forth on the validity of the Poletown stories. Many people swore by them and others brushed them off as folklore. What really blew me away was the conviction each person had. One day we would believe the stories were completely true and as grotesque as stated but then after talking to someone else we might think otherwise. By the end of it, we realized whether the story was true or not was less important than the fact the these were stories continued to be passed down and perceived as true by many to this day.

What are your three favorite/most influential documentaries or feature films?

I love Errol Morris’s Fog of War. In fact, I was very inspired by him when developing this film and its cinematic language. I love the film The Imposter because of the high-quality nature of the reenactments and how the filmmaker played with the dramatic question of whether something was true or not. Finally, I love the filmmaking style of Rachel Grady and Heidi Ewing in their [Independent Lens] film Detropia. They have a very soft touch that lets viewers sync into the subject matter on their own volition. I was inspired to bring that approach to Man on Fire.

What film/project(s) are you working on next?

I have another feature doc in development that looks at fundamentalism and how it affects our democratic process. I’m also working with a writer on a feature narrative film that takes place in Miami’s Coconut Grove where I grew up.