Roger Ross Williams won an Academy Award for his short documentary Music by Prudence, which told the moving story of 21-year-old Zimbabwean singer-songwriter Prudence Mabhena, who was born severely disabled and has struggled to overcome poverty and discrimination. For his first feature-length documentary God Loves Uganda, which itself was on the short list for an Academy Award this year, and premieres on PBS May 19th at 10pm (check local listings), Williams returned to Africa to tell another powerful, if far more chilling, story.

The film is “a searing look at the role of American evangelical missionaries in the persecution of gay Africans,” wrote Jeanette Catsoulis in The New York Times. Adds Andrew Lapin in The Dissolve, “one effective sequence after another carries the alarming sensation of ideological chaos without resorting to technical trickery.” We spoke to the filmmaker about the challenges of making God Loves Uganda and getting it to a wide audience.

IL: You grew up in the black church yourself, always had religion around you growing up, and know the powerful affect it can have on people’s lives. How do you think that experience has affected you as a documentarian?

Roger Ross Williams: My father was a religious leader in the community and my sister is a pastor. But for all that the church gave me, for all that it represented belonging, love and community, it also shut its doors to me as a gay person. That experience left me with the lifelong desire to explore the power of religion to transform lives or destroy them, thus motivating me to direct films like God Loves Uganda.

The film covers what is obviously contentious and provocative terrain — was your mindset going into it to get multiple perspectives, and was it difficult to do so, to get all sides to talk to you? (i.e., Christian fundamentalists, African religious leaders with differing perspectives, younger evangelicals, other Africans, etc.)

Absolutely. I knew the subject matter was a difficult and emotional one on many levels, as well as a very politically charged one. It was not difficult to get different people to talk to me once I was able to establish a space of mutual respect and trust. In addition, various parties were eager to share their own views about perceptions of homosexuality in Uganda and Africa in general.

Can you talk a little about your experiences going to Africa for the first time? How does the church there differ from the US church experience?

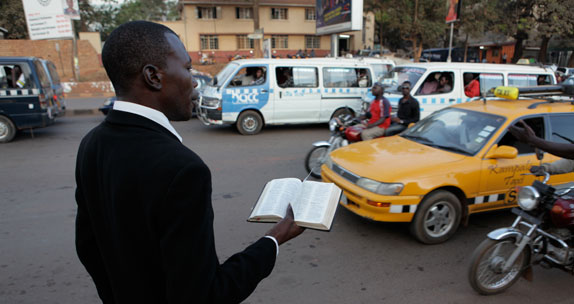

When I visited Africa to make my film Music by Prudence I was struck by how intensely religious and socially conservative Africans were. There was literally a church on every corner. People were praying in the fields. It was like the American evangelical Christianity I had known – but magnified by Africa’s intensity.

The more I learned about religion in Africa, the more intrigued I became. It was as if the continent was gripped with religious fervor. And the center of it was Uganda. I began to research; I took my first trip to Uganda. I discovered it is the number one destination for American missionaries. The American evangelical movement has been sending missionaries and money, proselytizing its people, and training its pastors for a generation; building schools, manning hospitals, even running programs for training political leaders. Its President and First Lady are evangelical Christians, as are most members of its Parliament and 85% of the population.

What were some of the biggest challenges you faced in making God Loves Uganda?

While shooting in Uganda in 2011, the conservative evangelical pastors I was filming — the most ardent supporters of the country’s now famous Anti-Homosexuality Bill — discovered that I myself am gay. One began circulating emails suggesting that I be killed. I left the country immediately, and hoped I’d never have to go back.

Cut to a year later. I’m with my editors at the Sundance Documentary Edit lab and it becomes abundantly clear that we need more footage from Uganda. We needed to spend more time there to do justice to this very complicated, and very important, story. And the only way to get it right meant I had to go back. Either I sacrificed, or the story would have to.

And so I went. I spent three terrifying, thrilling weeks in Uganda, knowing full well that this would be the last time I was in a country I’ve been filming for the past three years. And I’m happy to say that without the footage we captured on that last trip, God Loves Uganda wouldn’t be the film it is now.

Do you see any signs that attitudes about homosexuality may change in Uganda and other similarly minded African nations in the near future?

In the well-known trope about Africa, a white man journeys into the heart of darkness and finds the mystery of Africa and its unknowable otherness. I, a black man, made that journey and found – America. As unfortunate as it is that the role American evangelists played left a negative imprint on LGBT rights in Uganda, I choose to remain optimistic that Uganda will make the same political changes regarding homosexuality that we now see happening here in America.

And in your travels, did you find places in Africa that were more open and welcoming to LGBT people and lifestyles?

I found a very similar level of unacceptance in other parts of Africa, especially in Nigeria where we also screened God Loves Uganda. I wanted to make this film about faith and the different sides of faith, and the arguments going on, because if change is going to happen in Uganda and in Nigeria where there was a similar bill passed by the federal government of Nigeria, it’s going to happen in the faith community because they are driving this ideology and they are driving these types of bills.

What has the audience response been so far? Have the people featured in the film seen it, and if so, what did they think?

Most of the people in the film have seen the movie and some of the evangelicals have stated that it has made them more sympathetic and rethink how they spread God’s word in Africa.

Which films and/or filmmakers influenced you the most in making this film?

I was less inspired by other filmmakers in making this film, but instead moved by my first meeting with the late David Kato, an LGBT activist who was killed in 2011. When I first got to Uganda, he was the first person that I met, and after sitting down and talking to David he said, “you know what we really would love is a film about the work that the American fundamentalists are doing in our country, and how they were destroying their lives and the lives of the LGBT community,” and for me, because I grew up in the church, it really spoke to me.

What are you working on next?

I am working on a new film called Life Animated, The Documentary, based on the real-life story of Owen Suskind, the autistic son of the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Ron Suskind and his wife, Cornelia. The film is also based on Ron Suskind’s upcoming book, Life Animated: a story of Sidekicks, Heroes and Autism.

Essentially, the family is forced to become animated characters, communicating with Owen in Disney dialogue and song; until they all emerge, together, revealing how, in darkness, we all literally need stories to survive. The film is produced by Julie Goldman, and is a cinematic exploration into the magical world that Ron Suskind’s son has created. It is a story of a family finding hope and connection in very unexpected places.

What are your three favorite films?

Imitation of Life; The Celebration; and Darwin’s Nightmare.

What advice do you have for aspiring filmmakers?

Don’t be afraid to challenge yourself and go places you fear the most (both internally and externally).

Lastly, are there any updates on any of the people featured in God Loves Uganda that you want to pass along to us?

Yes. Bishop Christopher Senyonjo was one of the only faith leaders to stand up against homophobia in Uganda. The government is now threatening to arrest this eighty-one year old man, with a wife and many children. He was close friends with David Kato before Kato was murdered and is listed in the top ten of the world’s most influential religious people by the Huffington Post. Finally, there is an important book people should know about called American Culture Warriors in Africa: A Guide to the Exporters of Homophobia and Sexism, a new, popular-format guidebook written by Rev. Dr. Kapya Kaoma who was featured in the film, designed to educate U.S. audiences and motivate all people of conscience to take action that interrupts the persecution of women and sexual minorities overseas. [American Culture Warriors in Africa releases the same day as the national PBS broadcast of God Loves Uganda.]

See also: Roger Ross Williams on The Daily Show.