In celebration of Women’s History Month (every March), we focus on great recent documentaries about great women, all who forged their own path in times and places where that wasn’t expected or encouraged, especially for a woman.

As director Brett Morgen told WBURG of Jane (2017), his documentary about famed researcher Jane Goodall, “This is not a film about science… This is a love story about a woman and her work.”

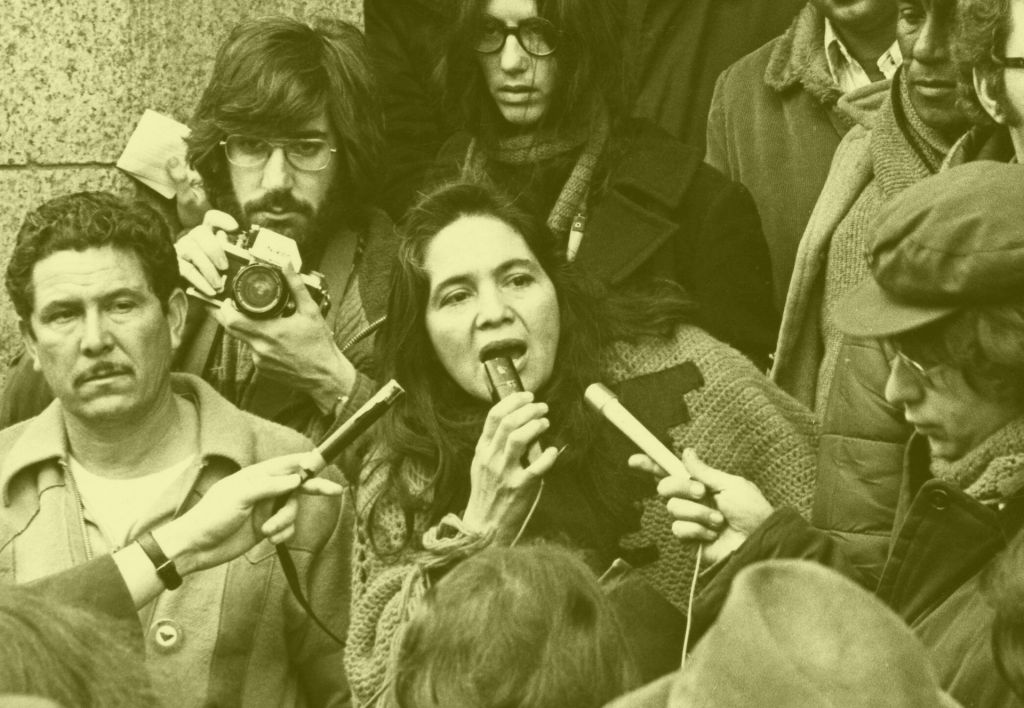

Dolores Huerta

Everyone knows César Chávez, but few know the name of Dolores Huerta, the woman who co-founded UFW, the nation’s first labor union protecting farm workers. She coined the rallying phrase “Sí se puede,” which became Barack Obama’s campaign slogan “Yes we can.” (Obama thanked her in person at the Presidential Medal of Freedom ceremony in 2012.)

Peter Bratt’s documentary about Huerta shows that she was alongside Chávez every step of the way. Having already gotten legislation passed ensuring public assistance for non-citizens, Huerta and her seven children relocated to Medina, California to live with the farm workers. Like Chávez, she was at every picket and every negotiation with the growers. But while he didn’t believe a nationwide union was possible in their lifetime, she did.

In a telling 1973 TV interview, an unseen female interviewer directs her questions mostly to Chávez, including this jaw-dropper; “What made you pick Dolores, a woman, to help form the United Farm Workers?” Huerta has an amused smile on her face as Chávez answers, “Dolores being out there made it okay for women to be there on the picket lines… We found that it’s a tremendous advantage to give women equal participation in the union.”

When the interviewer finally asks Huerta a question, it’s equally insulting: “Don’t you have the average woman’s dream of going out to a spa and having a great new hairdo?” Huerta smiles again and politely answers, “For me, going to a spa and having a new hairdo would be a terrible waste of time.”

In almost every photo of protests, meetings, and historic agreements — including getting the growers of California to accept the UFW — Dolores is the only woman in a group of men. After Chávez’s death in 1993, the all-male board of the UFW opted to back another man instead of its female co-founder.

Jane Goodall

Jane Goodall, one of the greatest living scientific researchers and environmentalists, was dismissed as just a “comely lass” (as one contemporary headline memorably phrased it) when news of her pioneering research was first reported in the ’60s. Despite her earth-shattering news that chimpanzees made and used tools (a skill thought reserved only for humans), the media focused exclusively on her looks, instead of her findings.

Goodall, who had no scientific training, got the Gombe assignment through famed paleontologist Louis Leakey. Goodall, a lifelong animal lover, first contacted him in 1957 and became his secretary. Wanting someone with no preconceived ideas about chimp behavior, Leakey sent her to Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania and the rest is scientific history. [Brett Morgen’s film Jane is playing in theaters and is available for purchase via the usual outlets starting March 13.]

Hedy Lamarr

Some of the most groundbreaking women have been dismissed as just a pretty face. That’s not surprising for Austrian-born actress Hedy Lamarr, star of such films as Algiers and Samson and Delilah: She was dubbed “The Most Beautiful Woman in the World” after arriving in Hollywood in 1938.

It wasn’t known until after her death that she’d co-invented the radio technology that paved the way for Wi-Fi and Bluetooth. During World War II, she and composer George Antheil came up with a secure communication system to help the Allies. The patent expired in 1959, so Lamarr never saw any money from its use.

Lamarr never even mentioned the invention in her 1966 ghost-written autobiography. But in Bombshell, director Alexandra Dean unearthed old interviews where we learn that Lamarr’s mechanical inclinations began in childhood. She even advised movie mogul Howard Hughes to streamline his plane designs to make them more aerodynamic. Hughes’s reaction: “You’re a genius.”

Her part in her own invention was largely unknown at the time of her death in 2000. She and Antheil were posthumously inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2014.

More on NPR, 2014:

[custom_html]

Agnès Varda

Agnès Varda, who would become known as “the mother of the French New Wave,” was able to bypass the formal apprenticeship approach to filmmaking in 1955 France and fund her own first film. As she says in a 2007 interview, “I looked for funding. I had no money, and no one backs films like that. I inherited a small sum, and my mother sold something of hers to loan me some money. We decided — and this too was revolutionary —that the film would cost 10 million old francs. Back then, an average film budget was 150 or 200 million.'”

Varda, now 89, still has that same sense of enthusiasm and spontaneity. In Faces, Places (which won an Independent Spirit Award and an Oscar nomination), she travels the French countryside with 30-something street artist JR. Together, they take pictures of ordinary people and make them into local celebrities by turning their images into barn-sized posters. [Editor’s Note: Varda sadly passed away on March 29, 2019, after this article was originally published.]

As she told the NY Times in 2001 about her documentary The Gleaners and I, “I’m like those old painters who don’t bother to make sketches or ask permissions. They don’t give explanations. They just go ahead and do it.”

Elsa Dorfman

A DIY approach also benefited Boston photographer Elsa Dorfman. She became known for her portraits of musicians and authors, including good friend Allen Ginsberg, and her use of large-format Polaroid photos.

She used to sell her photos on the street for $2, using a shopping cart and a hand-lettered sign. “The police would come and want to chase me away and I had a letter that Harvey (attorney Harvey Silverglate, her future husband) had composed that said I was protected by the First Amendment. And I alerted the Chief of Police and they let me stay there,” she recalls with a laugh in Errol Morris’s documentary about her, The B-Side.

Suzanne Ciani

When pioneering electronic musician Suzanne Ciani found that, in 1974, no one wanted to sign her to a record label, her persistence and ingenuity helped her carve out a brand-new niche in advertising.

“We didn’t know the words ‘sound designer’ back then,” Ciani recalls in Brett Whitcomb’s documentary, A Life in Waves, “but I said [to advertising execs], ‘I have an electronic instrument and I make sounds. I’d like to meet with you.’”

She kept getting stood up by Billy Davis, music director at the McCann Erickson ad agency, so one day she’d simply had enough. “I went marching up to Times Square, knocked on the door of his studio and walked into the control room.'” Her timing was perfect: He happened to need the perfect sound for the moment when the Coca-Cola cap is popped. And thus Ciani crafted one of the most iconic sound effects in advertising. She went on to create unique sounds for Atari games and was finally given a chance to record her own Grammy-nominated electronic music.

Ciani studied under synthesizer designer Don Buchla, who taught at UC Berkeley. That mentorship might have ended the very first day when Buchla found a badly soldered joint and, figuring it was Ciani’s fault, fired her. But Ciani refused to stay fired. “I just came back the next day, and I said, ‘You can’t fire me.’ Don was a tough cookie, but I was also very determined,” she shares.

A similar scenario played out with Huerta and Chávez, we learn in Dolores. After joining up with Gloria Steinem in New York during the famous grape boycott, one of Huerta’s daughters recalls, “She stood up for herself more. She wasn’t asking for permission. She just did what needed to be done.” That lead to clashes with Chávez, who would then say, “You’re fired.” “She’d say, ‘I quit,’ but she’d be there, the first person in the office the next day,” her daughter recalls.

Meanwhile, Ciani, now 71, after founding her own company Ciani/Musica in 1974 and her own music label in the ’90s, crowdfunded the documentary via Kickstarter. In 2017, she was awarded the 2017 Moog Music Innovation Award.

Ladies in Their Eighties

Now in their 80s, Goodall, Huerta, and Varda are still active in their chosen fields. Goodall, 83, leaves the research to new generations. She continues her work in saving the planet and endangered species thanks to the Jane Goodall Institute and the Roots & Shoots program.

After retiring from the UFW, Huerta, now 87, formed her eponymous foundation. A number of her daughters work with her to help empower the next generation of community organizers.

And while Faces Places might be Varda’s last film, the 89-year-old filmmaker hasn’t given up art. As she told Indiewire in 2017, “I”m not sure I’ll make another film… But I also do exhibitions, installations. I’m not going to bed.”

Appearing at a retrospective in New York, she said she had intended her 2018 biographic film The Beaches of Agnès to be her last movie. And then she met JR, 50 years her junior, who became her first collaborator. “Aging for me is not a condition, but a subject,” she said. With great humility (and humor), she lets JR film her doctor’s appointments — and stage a larger-than-life eye-chart with people waving letters to reflect her fading eyesight.

For Dorfman, who turns 81 this year, reflecting on her photographic archives brings a bittersweet nostalgia. Many of her subjects, including Ginsberg, are now dead. “Having all the pictures, you search for the narrative. But there is probably is no narrative. It’s just sort of what happened. It doesn’t go by a script. Maybe that’s when photographs have their ultimate meaning — when the person dies.”

She admits her work was unappreciated while shooting her most famous subjects: “What amazes me is you just have to wait long enough. My work was so rejected and it adds to the pleasure of people liking it now. For so long, I was at the bottom of the list. Somehow, I just kept plowing along.”