“Besides a well, one does not thirst. Besides a sister, one does not despair.”

— Nüshu poem

Inspired by a bestselling book that featured Nüshu, filmmaker Violet Du Feng was surprised at how little she and most Chinese people knew about the secret written language that goes back centuries in China. The Shanghai native and New York resident Feng became obsessed with Nüshu as she began seeing ways its ancient story connected to modern women in China struggling in a patriarchal society.

The Oscar-shortlisted documentary Hidden Letters examines the only script designed and used exclusively by women that shows how friction has developed in China over the commercialization and control of Nüshu. But ultimately Feng’s documentary—which she co-directed with Qing Zhao—is the story of the bonds of sisterhood. To that end, Hidden Letters spans past and present, as two young women try to continue the tradition while fiercely protecting it.

What is Nüshu?

Violet Du Feng: For centuries leading up to the Communist Revolution in 1949, Chinese women following the “Three Obediences”—to obey fathers in childhood, husbands in marriage, and sons in widowhood—succumbed to the oppression of patriarchy. Foot binding was prevalent, women were often relegated to private domestic settings, away from the public gaze, and unmarried girls spent most of their time doing needlework with peers in the upstairs chamber of a house.

Yet persistent struggle led to eventual resistance, and when the written language of Nüshu emerged in Jiangyong, a remote village in Central China, one of the most extraordinary and pioneering forms of feminist protest was born.

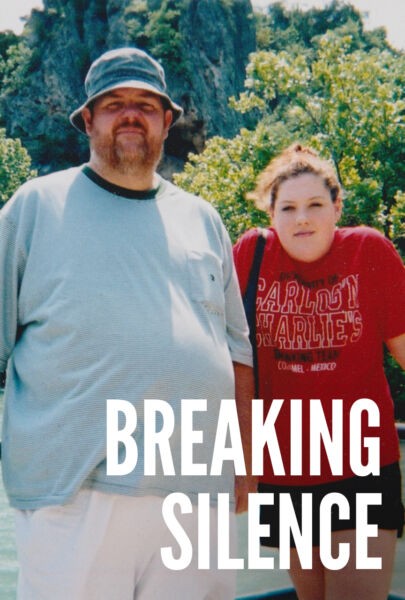

Filmmaker Violet Du Feng

Nüshu was created by and for women to commune in privacy. As a secret text, Nüshu was written in calligraphy as poems or songs on paper-folded fans and handkerchiefs. These hidden letters were passed down from generation to generation as a way for women to share their stories, express hope and solidarity, and affirm their dignity in the face of daily struggles.

In a world where there was almost no female literature, most women [in China] had their own written biographical ballads.

How did you learn about Nüshu?

Violet: In 2005 I read about Lisa See’s critically acclaimed New York Times bestselling novel Snow Flower and the Secret Fan. The book, based on a female friendship forged through Nüshu, has sold 1.5 million copies and was later made into a movie directed by Wayne Wang. I was so amazed about the existence of Nüshu, which most Chinese, including me, knew nothing about.

Working in film for so many years, I’ve always wanted to tell stories that are different and bring a fresh voice about China, different from the mainstream media. I was very much feeling drawn to doing something about a women’s issue that hasn’t really been talked about. Two producers, Mette Cheng Munthe-Kaas and Jean Tsien, approached me to do a film about Nüshu. I knew I wanted to tell a contemporary story, to connect Nüshu with the state of women’s rights in today’s China.

“We don’t feel there’s a way to talk about women’s issues in China.”

How does this project resonate with your own feelings as a woman and a filmmaker?

Violet: I grew up in China when the state provided free daycare but I was raised mostly by my dad and I never thought I could dream any less than a boy, just because I’m a girl. My dad always gave me that kind of hope, and my mom was the first-generation medical staff in our family and took great pride in her career.

I moved back to China in 2010, where I was producing films for emerging first-time female filmmakers from China. So I was more in the Chinese industry, where I understood how patriarchal it was, and that was also when I got married and… became a mom that I suddenly felt society’s expectations on me were to be a good wife and mom.

A lot has to do with the way our society has become capitalistic with the vastly expanding gender wage gap. I felt stifled, and all my girlfriends felt the same. We don’t feel there’s a way to talk about women’s issues in China.

In China today, how is feminism viewed?

Violet: When I started the project in 2017, the regression of women’s rights in China was still a political taboo. The English “#MeToo” hashtag only had a fleeting moment in China before the online censors swooped in to block it. Even the word “feminism” was largely denounced.

But every time I had conversations with female friends and relatives, or women I met at places like nail salons or bank appointments, everyone shared the same sense of frustration, anger or suffocation against our entrenched gender roles. I realized the urgency of using this film to provide a shared platform for women to start the conversation, just as what Nüshu did to those women in the past.

What brought you to your main participants, Hu Xin and Wu Simu?

Violet: I met Hu Xin during my first scouting trip to the village next to where the government built the Nüshu Museum [where] Hu Xin is a museum tour guide. At first, she presented herself more as a government spokesperson, promoting Nüshu to the press and at events, but I later found out she’d been struggling for years to conceive a boy to satisfy her husband, and just divorced because of that.

She said to me, “I felt like a failure as a woman.” I knew she was at a vulnerable crossroads, which I could so relate to. I came to a deeper understanding of the strength she found in Nüshu.

I met Simu through Hu Xin, who taught her Nüshu. She was one of the few whose motivation for Nüshu was to preserve its dignity and legacy, not fame or wealth. Simu was part of this female artist community, using art to explore gender identities, and her tool was Nüshu.

Simu

What was it like interacting and working with the remarkable grandmother and mentor He Yanxin?

Violet: She is so amazing. I initially wanted her to be the main character. And I wanted to follow her granddaughter, who knows Nüshu but abandoned it and went into the city to find a job. There’s a book about He Yanxin and I knew her life story, and what a tough cookie she is because of Nüshu. She embodies the spirit of Nüshu to me.

The first time I went over, she wouldn’t even talk to me because she thought I was sent by authorities. She told me, “You will not turn on the camera.” When I knew that Hu Xin had this bond with her, that made me so happy. I knew how much she was transferring her heart and her authentic legacy of Nüshu to Hu Xin. It really helped Hu Xin out from her divorce. Nüshu is all about sisterhood.

Their relationship epitomizes Nüshu in that so long as women confide, listen, and bond to one another, the power of Nüshu will persevere. And that’s what we continue to need despite our differences in culture, religion, geopolitics or age.

Could you talk more about the battle to modernize and commercialize Nüshu?

Violet: The co-option and commercialization of Nüshu is one of the film’s themes, revealed in several scenes where men are engaged in various marketing schemes. It feels like “the more things change, the more they stay the same.”

The first time I went [on a scouting trip] I instantly felt there was something strange about it, because all these men in powerful positions were trying to take control of something that was completely created and shared only for women to resist the patriarchal society. Nüshu had become a metaphor. This very treasure that women created, even the last bit of what we own, they are trying to take it away.

In a way, China is very capitalistic, trying to commodify everything. But I was trying to use these scenes to help people see what men’s perspectives are on women. Women have moved forward so much with what we want to achieve, even in China, but men’s perception hasn’t really changed. The gap has become so much bigger. That’s what I wanted to show.

Hu Xin’s handwriting in Nushu

What kind of impact can films like this have back in China?

My previous film, Please Remember Me, is about Alzheimer’s [as seen in] an elderly couple who actually is my great aunt and her husband, and we told a beautiful love story between them. [It] actually created policy change. We could have gone with the approach that the elder care system in China is really messed up. It is. But there would be no way for it to be seen in China. And we could have been successful in the U.S., but that’s not what I think matters.

That’s why I call my company Fish and Bear. There’s a Chinese proverb that says you cannot have fish and bear paw at the same time. You can’t have both in your hands. [You can’t always get everything you want.]

NOTE: Check out the film’s virtual gallery of secret art, a space for women all over the world to “weave a landscape, with art, that allows expressions of vulnerability, resilience, and complexity of experience. Gallery selections will be curated by established artists in multiple mediums.”