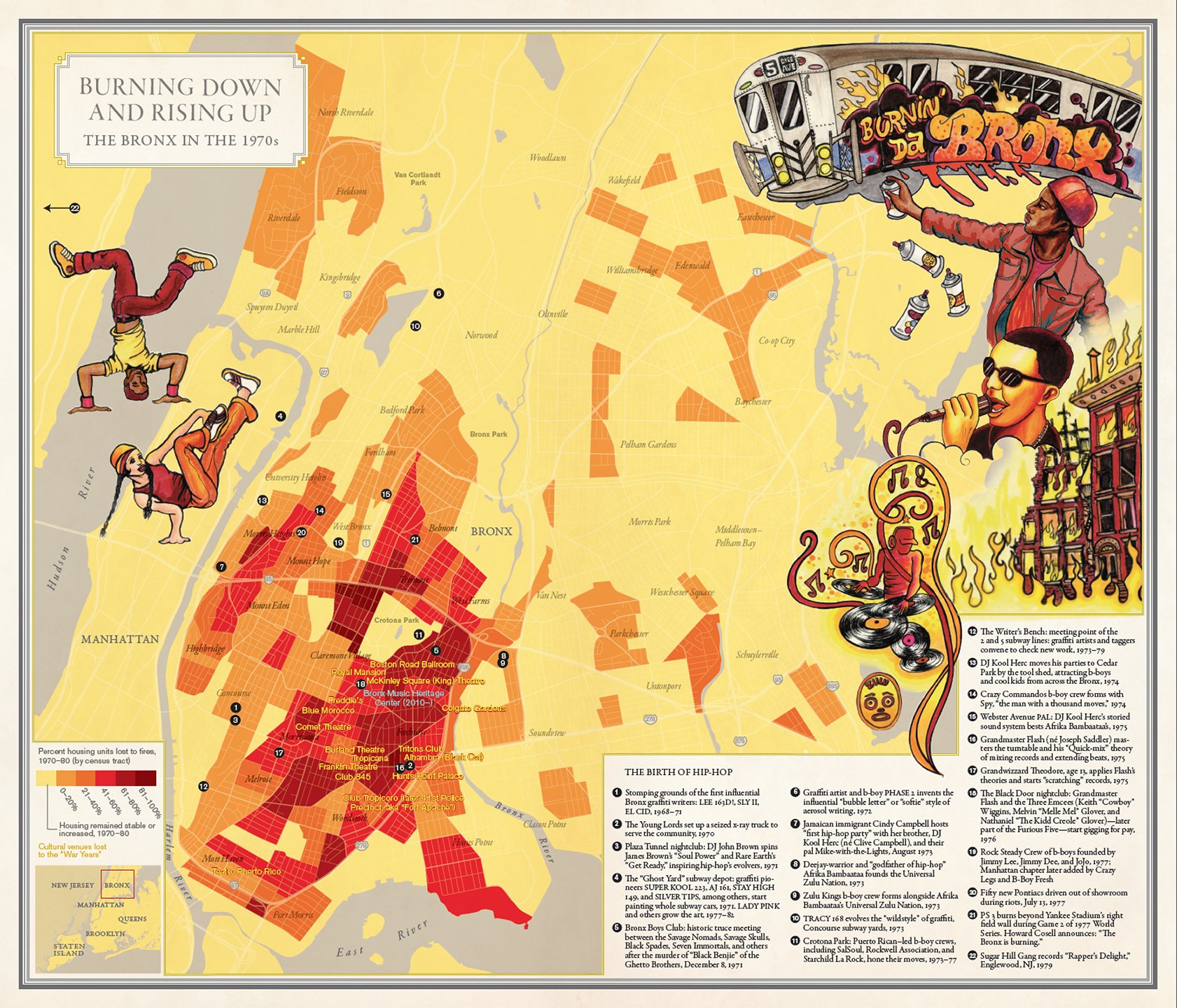

Joshua Jelly-Schapiro, a geographer and writer who co-edited, with Rebecca Solnit, the remarkable, fascinating book Nonstop Metropolis: A New York City Atlas, helped us create a playlist to accompany both Decade of Fire and a key map in his book: “Burning Down and Rising Up: The Bronx in the 1970s.” That map puts a geographic spin on a musical history, how hip-hop music rose from the ashes of the Bronx’s decade of fire.

By Joshua Jelly-Schapiro

“We were in a place where we just needed an outlet, where we just needed something to make a day normal.” That’s how Melle Mel—legendary MC, founding member of the Furious Five, lead vocalist on the history-making hip-hop classic “The Message”—describes growing up in the Bronx in the 1970s. New York City was bankrupt. And across broad swaths of the South Bronx, landlords were paying arsonists to torch their buildings for insurance money as the city—advised by the RAND Corporation to close fire stations and let its poorest areas burn—let it happen.

But if those fires, and the larger urban decline they signaled, defined the ’70s in the Bronx, so, too, were those years marked by the “outlet” that Melle Mel describes. That outlet was hip-hop: a complex of culture comprised of music (rapping, DJ’ing), dance (breaking) and art (graffiti) that remains a vital lingua franca of youth culture, around the globe, four decades later.

How can it be that this awful era, when a major American city came to resemble the bombed-out burghs of Europe after World War II, also comprised the seedbed for what’s arguably New York’s most potent and lasting contribution to contemporary culture?

That was the question behind “Burning Down and Rising Up,” one of 26 maps that my collaborator Rebecca Solnit and I, along with a brilliant crew of designers and artists and scribes, created for Nonstop Metropolis: A New York City Atlas. That book, the third in a trilogy of atlases of iconic American cities, was predicated on the idea that all cities contain at least as many ways to be mapped as they do people; that beautiful paper maps may remain an unexcelled technology, even in our digital age, for organizing information and telling stories about place; that such maps possess a unique power to surface hidden histories, and draw connections, that help us see our homes in fresh ways.

It was in this spirit that we sought, in this map of the Bronx’s darkest decade, to also chart a remarkable flourishing of culture, from the ruins of the fires.

What emerged, in doing so, was striking. The urban scholar Jonathan Tarleton, collating data from the census bureau, worked with our cartographer Molly Roy to craft a stark tableau of urban destruction: an image of a borough where in some areas of the South Bronx—the dark red areas on the map—upwards of 90% of housing units were lost between 1970 and 1980.

Onto this background of flames, we then sought—with the help of Elena Martinez and the Bronx Music Heritage Center, and oral history interviews with hip-hop icons like Melle Mel—to chart the seminal moments and places of its birth: where Grandwizzard Theodore first scratched a record; where DJ Kool Herc’s big sister, Cindy Campbell, threw “the first hip-hop party”; where the b-boys and breakers of StarChild La Rock, in Crotona Park, honed their craft.

And behold: the places where these things happened are the same ones that, during the Bronx’s awful decade of fires, were most harmed. It was from the ashes the fires left—the vacant lots and rubble and parties thrown with equipment won during riots and blackouts—that hip-hop’s phoenix rose.

When we heard about Decade of Fire, this was cause for thanks: the story this film tells is one that the Bronx, and New York City, and the world, needs to know. Not least because it’s a story about the harm that neglect and malfeasance and urban governance at its worst can yield. But also because it’s a film which knows that the tale of the Bronx in the ‘70s, and since, is also one of persistence, and of rebirth.

In an essay we published with this map in Nonstop Metropolis, Marshall Berman explained why.

Berman, a great urbanist who was also a native son and lifelong devotee of the Bronx, described hearing “The Message” for the first time, banging out of a West Harlem record shop in 1982. Its young makers had come of age in the city’s worst period—they’d grown up on the precipice of ruin (“Don’t push me / ‘cause I’m close to the edge…”).

But they’d survived, with imaginations intact, to create a masterpiece of urban realism, as Berman called that record, “that looked the negative in the face and lived with it, and still dreamt of coming through.” Hip-hop was the sound of a city surviving. Hearing “The Message” was what convinced Berman that the city would be alright. When he knew, as the people of New York’s toughest borough learned long ago, that you can’t burn imagination.

Map credits:

“Burning down and Rising Up” by Joshua Jelly-Schapiro and Rebecca Solnit

Cartography by Molly Roy

Design by Lia Tjandra

Research by Jonathan Tarleton, Mirissa Neff and Garnette Cadogan

Art by Lady Pink

MORE:

The South Bronx: Where Hip-Hop Was Born, from WNYC

Joshua Jelly-Schapiro is a geographer and writer. He is the author of “Island People: The Caribbean and the World” (Knopf, 2016) and the co-editor, with Rebecca Solnit, of “Nonstop Metropolis: A New York City Atlas” (California, 2016). He is a regular contributor to The New York Review of Books, and he has also written for The New Yorker, The New York Times, Harper’s, The Believer, The Nation, Artforum, American Quarterly, and Transition, among many other publications. His work, which often focuses on place, race, and how human difference is thought about and acted on in the world, has been supported by fellowships from the National Science Foundation, the American Council of Learned Societies, and the Social Science Research Council. He earned his PhD in geography at UC-Berkeley, where his doctoral thesis was awarded the Best Dissertation Prize from the Caribbean Studies Association. He is a visiting scholar at the Institute for Public Knowledge at NYU, where he also teaches.