Laura Dunn’s first feature documentary, The Unforeseen, executive produced by Robert Redford and Terrence Malick, premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, aired on the Sundance Channel, and was called “a poetic and high-minded meditation on American developers’ manifest destiny and the cancer it introduces into the natural world,” by critic David Edelstein. It explored a real estate development encroaching on a favorite natural spot in Austin, Texas. Her new film, Look & See: Wendell Berry’s Kentucky.

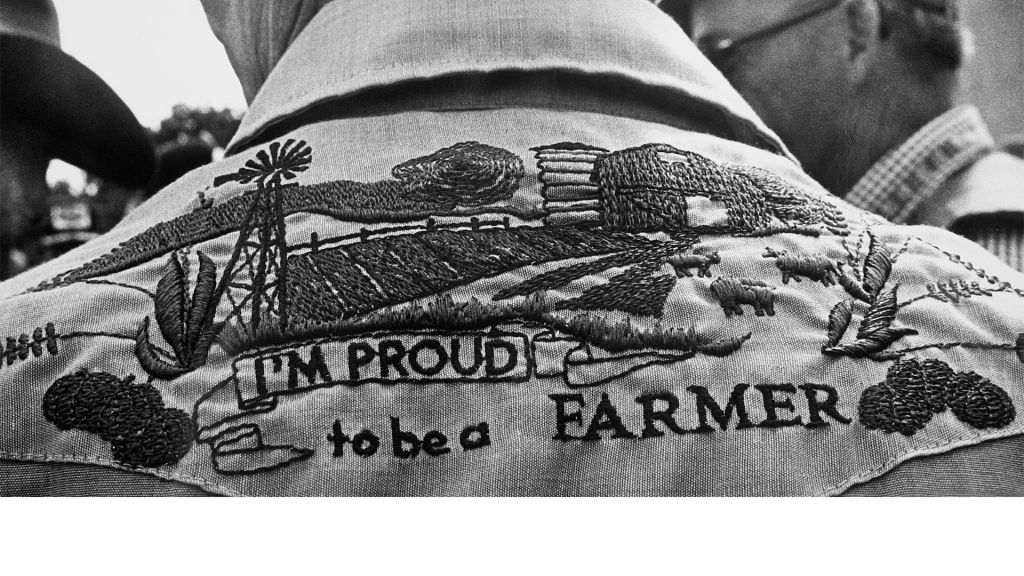

Look & See is a portrait of the changing landscapes and shifting values of rural America as seen through the mind’s eye of the titular writer, farmer, and activist Berry, in his native Henry County, Kentucky. As shown in the film, Berry, whose voice is heard throughout the film though he never appears on screen, famously butted heads with US Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz over a more profit-oriented, corporate approach to farming that removed the “culture” from agriculture.

Look & See is an “unusual and quite beautiful documentary,” writes The Hollywood Reporter. It’s “deeply moving and richly satisfying, [an] unusually fine documentary,” adds Catholic News Service. Dunn talked to us about why she wanted to make a film about Berry and an increasingly bygone way of life.

Why did you make Look & See?

Wendell Berry is one of my favorite writers and one of the seminal living writers in American literature. I wanted to draw more attention to his work.

Who do you hope your film impacts the most? And what discussions would you like viewers to have with each other after they see Look & See?

I hope it helps small family farmers. I hope that it sensitizes urban consumers to the economic challenges that our producers face. And I hope that, in general, it sensitizes viewers to rural America and the beauty, complexities, and struggles there.

I would be so happy if the next time someone drove through a small town, they did not snub their nose or silently dismiss the place and the people but rather considered it. I think that the rural-urban disconnect is a huge problem for this country, and I very much want to portray rural America as an essential, vital, beautiful and complex place with so much to teach us.

How did you gain the trust of both Berry and his family, and the farmers you include in the film?

We spent a lot of time there with our kids just being a part of things. I also wrote many letters back and forth with Wendell. And Tanya Berry made many calls on our behalf, which helped tremendously because she’s a beloved member of her community.

Could you talk a little about how your previous film The Unforeseen, which also dealt with environmental themes with a very human face, connects with this film? How did that experience inform the making of Look & See?

The title for The Unforeseen was actually drawn from a Wendell Berry poem from his Sabbaths collection (“Santa Clara Valley”). That film documents real estate development in my hometown of Austin, Texas and its impact on a spring-fed swimming hole at the heart of the community. Executive Producer Terrence Malick encouraged me to look at some writers who could contextualize our local story in a broader frame. One of those writers was Wendell Berry, so I spent time revisiting his work.

“The rural-urban disconnect is a huge problem for this country, and I very much want to portray rural America as an essential, vital, beautiful and complex place with so much to teach us.”The poem is this beautiful walk through “the deserted prospect of the modern mind” where everything is planned and nothing is unforeseen. He paints this picture of a landscape effaced and completely remade over in man’s image where “no comely thing could grow comely on its own.” At the end of the despairing walk, he comes across a little pool of water and in it springs forth resilient life. This poem served as a kind of guidepost for me when editing that film, a way to find hope in what felt like a hopeless landscape.

Wendell was kind enough to contribute an audio recording of him reading that poem, and his voice becomes a kind of poetic narration intermittently throughout The Unforeseen. When we toured that film, I was struck by how few people seemed to know of him, and so I wanted to do what I could to draw more attention to his work.

How did folks like Malick, Robert Redford, and Nick Offerman get involved with this new film as producers?

I worked with both Malick and Robert Redford on The Unforeseen. Redford asked me what I wanted to do next, and I told him that I was re-reading The Unsettling of America, and wanted to do something to draw more light on Wendell’s work. That book had been important to him when first published in the ’70s, and he generously encouraged me to move forward.

A very dear and mutual friend introduced Nick to us about half-way through production. Nick does a lot of work in Austin, and so our worlds fortunately overlapped. Nick has long been a big-time fan of Wendell Berry, and he has been a true champion. Terrence Malick is the very best mentor imaginable and gives me invaluable feedback on edits.

What were some of the biggest challenges you faced in making this film?

Chasing farmers is tricky because everything is 100% contingent on the weather, and of course that is totally unpredictable. It also took a lot of time to earn the trust of folks in rural Kentucky because they are mostly private and reserved people who are used to being made fun of in the media.

Also, our subject, Wendell Berry, does not regard screens of any kind as a viable artistic medium. So we had to work around that limitation.

Do you hold out hope that the small family farm can remain a thing in America? How can Americans protect this tradition?

When asking Wendell a similar question, he replies, “Hope’s a virtue, so you’ve got to have it.” I see family farms thriving in Henry County, and it takes commitment and hard work. Many farmers there would comment on their situation and call it “a hard life but a good life.” I think you have to hold fast to those defining American values Wendell articulates in the film–of independence, thrift, hard work, neighborliness, and you have to choose the harder path most of the time, but the rewards are great, and yes, I think we can protect these traditions with that kind of spirit.

You can also see a shining example of vision and hope in Henry County through the work of Mary Berry and her team at The Berry Center. Building a healthier economy for local farmers through education, initiatives, policy work and historical preservation, they serve as a wonderful model for the renewal of rural communities.

How are people in Kentucky relating and connecting to your film?

We’ve done several screenings there—in Louisville, Lexington, on rural farms throughout the state, at the Henry County High School—and I have been encouraged by the response. I hope that Kentuckians feel that the film treats them with respect and care in the way that Wendell’s work has done for rural people and communities.

What are your three favorite/most influential documentaries or feature films?

Fred Wiseman’s films, American Dream by Barbara Kopple, Touching the Void.