It’s not often you’ll find a documentary filmmaking team who combined have won an Oscar, an Emmy, and a Grammy, but the multi-faceted duo of Morgan Neville and Robert Gordon have done just that. Neville’s 20 Feet from Stardom won the Oscar for Best Documentary and Hank Williams: Honky Tonk Blues took an Emmy; Gordon’s album notes for Keep an Eye on the Sky, a box set retrospective for the band Big Star, earned him a Grammy. The duo collaborated in the past on another music doc: Johnny Cash’s America. So what brought them together to make the politically-minded Best of Enemies?

Gordon and Neville told The Wrap they were inspired after watching bootleg copies of the famed (or infamous) William F. Buckley-Gore Vidal ABC News debates and saw an opportunity to make a film about “the culture of politics” that would have great resonance today.

The “deliciously feisty” (Entertainment Weekly) film has its television premiere on PBS Monday, October 3 [check local listings]. Critic Bilge Ebiri of New York Magazine called the Oscar shortlisted Best of Enemies “masterful…leaves you with an overwhelming sense of despair. It’s not just a great documentary, it’s a vital one.” Director Gordon, along with contributions from a very busy Neville, spoke to us more about the challenges of making a historical film that still had potential to be politically charged, on working with actors Kelsey Grammer and John Lithgow, and on the story’s connection to today’s TV political coverage, plus recommendations for further Gore-y reading.

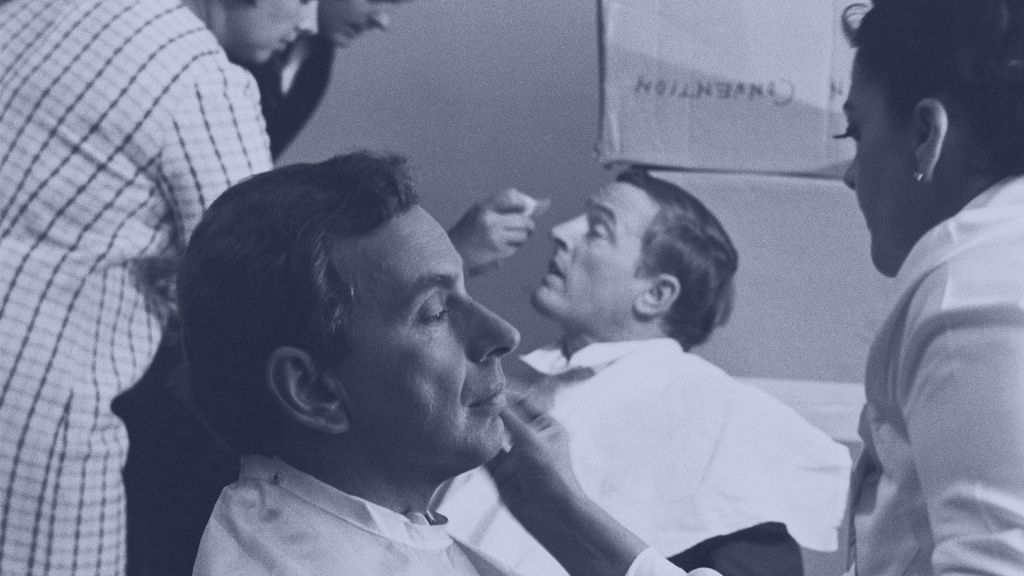

Best of Enemies Filmmakers Robert Gordon and Morgan Neville

There were probably a lot of challenges but what were some of the biggest you faced in making Best of Enemies?

We had a fundamental cinematic challenge: how to make a visually compelling movie about two talking heads. Both Gore Vidal and William F. Buckley Jr., however, lived well-televised lives, so we had plenty of material outside the debates to work with. And since much of their subject matter and issues that they devoted their lives were major issues of the day, we had a wealth of archival material to draw from. We were bolstered, too, by the fact that the dialog between these men was fast, sharp, and as brutal as a heavyweight championship boxing match, creating a fast and furious fundamental tone on top of which we could build.

What would you have liked to include in Best of Enemies that didn’t make the cut?

This film plays as a complete whole, but there were more instances of their parallel lives that we could have focused on, such as the arc of their publishing careers. A difference between them that was outside the scope of the film but very interesting was their opposing religious beliefs: Buckley was a staunch Catholic, and Vidal a firm atheist. Also, we had over two hours of raw debate material to work with, so there were plenty of sharp, witty repartee that we could have worked in, and choosing which parts to use was quite difficult.

Is there any scene or moment in the film that is especially moving for you or has the most resonance?

About ten days after interview with [author and critic] Christopher Hitchens, he announced a surprise cancer diagnosis and died about 18 months later, three and a half years before our film was released. Hitchens was in many ways the inheritor of the public intellectual mantle that Buckley and Vidal represented — intellectuals who embraced TV and were able to convey big ideas with clarity and humor. With Hitchens’s death, that era of public intellectuals ended, and seeing him in the movie — healthy and energetic — is always poignant.

Our position not to pick a side, but to stand far enough back to try and grasp what makes the sides, the pundits, behave like they do.Could you talk about the film’s balanced approach? Best of Enemies really does seem to go out of its way to give air-time to all sides. How conscious of this were you when editing to achieve balance?

Audiences have been consistently surprised that we didn’t choose a side, that we didn’t jam a position down their throats. And that consistently surprises us. [It] seems to say a lot not only about programming today but also about audiences, i.e., viewers assume a position is being taken in the media. Our position not to pick a side, but to stand far enough back to try and grasp what makes the sides, the pundits, behave like they do.

We did strive for balance, but it wasn’t a mathematical approach. It was more about feel. We could not control the debates — they were inherently what they were, but we did work on balancing the ancillary material. In part, that had to do with seeking emotional chords we could strike with each man. Both men had led such televised lives that there was no shortage of material (only a shortage of time to wade through it all). In our test screenings, we would ask how people felt about each character and would sometimes tweak accordingly.

In part, the whole exercise was aided by our own feelings. Though the filmmaking team, as a whole, tilted toward center-left, we all were charmed by Buckley and the more we learned about him, the more we liked him — especially as a person, politics aside. Ultimately, we were subject to what the footage told us, and we tried to stay true to the footage. It seems like we did.

Buckley was deceased when we began the movie, but Vidal was alive. We did interview him, but we decided not to use the interview in the film, mostly because he’d already gotten the last word by writing the scathing Buckley obituary. We felt that giving him a coda to the last word would take away the balanced view we were seeking.

Were any of your many interview subjects a particular challenge to get to talk about this, or were they all eager?

When we began exploring the idea (in 2010!), we felt like it was a good idea but we weren’t sure. And since our backgrounds weren’t in political film, we didn’t know if we’d be accepted. But our first round of queries affirmed the validity of the idea and assuaged our fears about credentials. Christopher Hitchens was our main bellwether. When we inquired with him (before his diagnosis), he was bursting with enthusiasm. Same with [essayist and former NYT columnist] Frank Rich. Our first round of interviews, in addition to those two, included James Wolcott, Dick Cavett, and Reid Buckley, Bill’s brother. We knew, when the interviews were done, that we had a great film to make.

Though we both have backgrounds as journalists, our focus has been directly on political punditry. However, we found little resistance. Our interview subjects recognized we’d seized upon an important historical moment with great contemporary relevance, and they were happy to participate.

Who were some of the political pundits you grew up watching? Who did you find the most riveting?

I grew up in Memphis and in the 1960s there were three stations to watch. On Sunday mornings, before cartoons came on, we’d flip the dial on the black and white TV: Preacher, preacher, Buckley (a political theologian). We’d always stop and watch Buckley, not because we wanted to hear what he said — we were too young to follow his sesquipedalian vocabulary — but because he was riveting, slouched from one side of the screen to the other, smoke curling up from his cigarette, his accent like a foreign language song.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x7IRKloX8iU

This is projection, of course, but what do you think Buckley and Vidal would think of today’s political commentators? Is there anyone who comes closest to the ideals and personality of each one? Is there any hope for the future when it comes to finding intelligent political commentary on television?

I have a naïve hope that public intellectuals will be invited back to TV because the programming is cheap to produce. Sooner or later, some failing station will need something new to do and since so many ideas are so tired, and since so many stations are so formulaic, and since producing talk programs is so relatively inexpensive, I feel like some executive is going to say, like the programmers at ABC in 1968, “Let’s give it a whirl.”

And though there are few (if any) public intellectuals on TV, I don’t believe the species is extinct. They are in the universities and in the think tanks, and when people find out that one aspect of intelligence is wit, and that watching people discuss serious issues can be fun, the notion of intelligent talk will begin a comeback. Pundits today tend to pique emotions, to satisfy audiences by raising their anger at the opposition. It isn’t about establishing ideas, it’s about stoking rage.

What was it like working (even if briefly) with Kelsey Grammer and John Lithgow, who did voice-over for the film?

Both were great, and were real pros. A quick story: Lithgow had been in a Vidal play long ago and had met Gore once. If I’m not bungling the story, Lithgow said that someone in the group asked Vidal if his first sexual encounter was with a male or female. Vidal was stoic and replied, I was too polite to ask.

What advice do you have for aspiring filmmakers?

Don’t take no for an answer! We applied many times for grants to make this film and were rejected several times before we finally got the yes we needed. If you really believe in your film, perseverance is the key.

What are your three favorite films?

Robert:

- When We Were Kings

- Bobby Fischer Against the World

- Myra Breckinridge

And what are some political films — or films in general — that were influential on you, or in your minds, when making Best of Enemies?

- Network

- Medium Cool

- (And again) Bobby Fischer Against the World

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pX6BM-myPqY

Since you listed Myra Breckenridge as one of your favorite films, I have to ask, do you think that book holds up today? The book was so groundbreaking in its time for all its taboo subjects. What other Vidal books would you recommend people read who are interested in learning more about him?

Myra alternates styles in each chapter, switching between narrative writing and dictation. Until voice recognition was integrated into cell phones, dictation was a dead or dying art. But now the text seems brilliantly anticipatory. And by the way, the film deserves a whole new look. Long slagged as the worst film Hollywood ever made, it too anticipates storytelling techniques that would become common — not quite fourth wall-breaking, but a kind of blender editing of the main narrative and unrelated films taken out of their original context and made to work as commentary on Myra.

Also, the film’s core subject matter couldn’t be more relevant in this age of gender fluidity. Ripe for remake!

Two other Vidal books of note: Inventing a Nation is a good way into Vidal’s sense of the founding fathers, a nonfiction summary of his fictional American biographies. Of the fictional biographies — all rooted in fact, if liberties may have been taken — the strongest one is Burr. And essays were Vidal’s great strength; these have been collected in various editions and you almost can’t go wrong with any of them.