Editor’s note: This interview with filmmaker Bill Siegel is brought to you in partnership with our friends at POV, and conducted by excellent, widely-respected independent journalist Tom Roston.

By Tom Roston

Wait, what, another Muhammad Ali documentary? I’ve always found the great Ali’s gift for gab and awesome boxing skills imminently watchable, but ever since When We Were Kings, the 1996 Oscar-winning documentary, watching Ali on screen has felt like a rerun. Often, a good one, but nothing new. Until now.

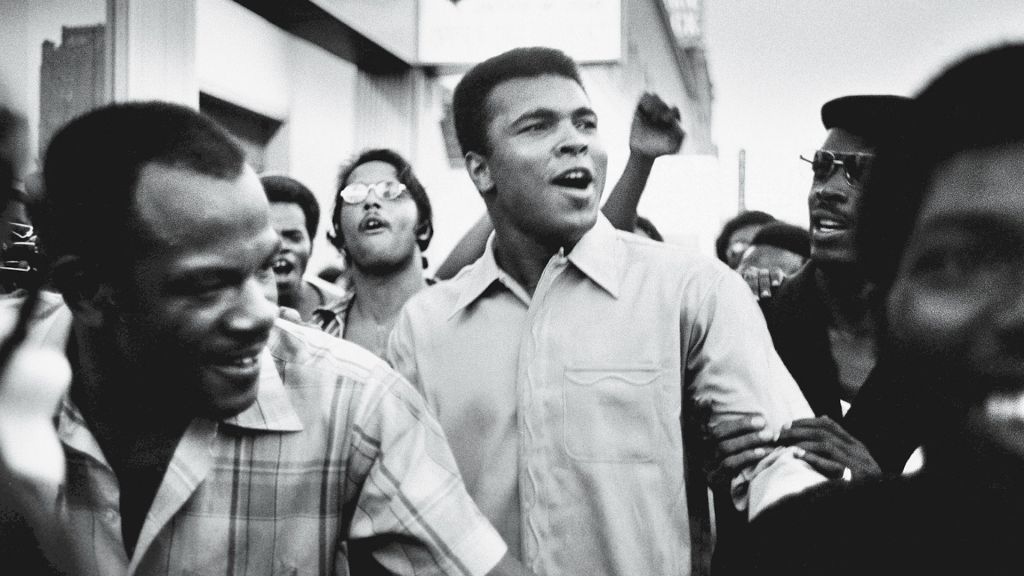

The Trials of Muhammad Ali is a purposeful look outside of the ring, at the political and social turmoil that Ali inspired and endured with his conversion to Islam and his refusal to fight in the Vietnam War.

I’ve been aware in broad strokes what happened, but director Bill Siegel delivers a cornucopia of details that I found riveting, from the Louisville Sponsor Group, a ring of old-world white businessmen who backed Ali in the beginning of his career to his hilarious (to me, at least) stint in musical theater, and especially to the criticism he’d get during interviews. William F. Buckley dismissing Ali is one thing, but to witness the utter contempt with which Jerry Lewis treated him, is jarring. I wasn’t aware until after seeing Trials that Leon Gast, the director of When We Were Kings, is an executive producer. Siegel got his start working with Gast on the ill-fated Muhammad Ali: The Whole Story, which after its collapse became When We Were Kings, so he’s clearly earned the right to jokingly refer to Trials as Before We Were Kings.

Doc Soup Man: The film makes a pretty strong argument that Ali’s greatest fights were outside of the ring. Was that your mission?

Bill Siegel: My mission was not to set up a bout between Ali the boxer and Ali beyond the ring, but I did know from extensive research I’d done over the years that the latter was a woefully under-regarded part of Ali’s life, especially insofar as how it’d been explored in documentary film. I was certain there was a worthwhile film to be made that would focus on his years in exile, one that wasn’t a boxing film, but was a fight film. Due to the seeming all-prevailing presence of Ali’s name, it was also a fight to get funders to realize there indeed was a deep story that still needed to be told about him. Fortunately, Claire Aguilar at ITVS got it right away. Then Lois Vossen [Deputy Executive Producer] at Independent Lens came on board and both have been real champions of the film.

Doc Soup Man: How do you think Ali’s political trials impacted his boxing? Did it make him a better boxer? Did it take away from his potentially best years?

Bill Siegel: Ali aged from about 25-28 during the exile years. Many people indeed think we never saw what would have been his prime years a boxer. I don’t know enough about boxing to say if that’s true, but it makes sense to me. When I watch his fights, pre- and post-exile, it seems to me he took a lot more punishment in the ring after he returned. I mean Ken Norton broke Ali’s jaw, he had the three fights with Frazier, all of Ali’s ring losses happened after he returned, it hurts to watch the Earnie Shavers fight, and I don’t even want to talk about the bout with Larry Holmes. Then again, Ali won two of the three Frazier fights, beat Norton and Shavers and regained his title in Zaire. Taken together, his pre and post exile bouts demonstrate good reason for why he’s called “The Greatest.”

Doc Soup Man: I can’t help comparing and contrasting every film about Ali with When We Were Kings. Does your film complement that one?

Bill Siegel: Leon Gast, who directed Kings is a good friend and mentor. We first met working on yet another Ali project in the early 90′s, my first gig in documentary. He’s been in my corner ever since and is an executive producer on Trials. While I was working on it, we jokingly called it Before We Were Kings, and I think it’s apt in a way. So yes, I think it complements Kings, but that film is also an incomparable masterpiece. I’ve said many times that you can fill a multiplex with Ali documentaries, but they pretty much all feature his boxing and again, because there is so much value to Ali’s life outside the ring, I felt there was room in the multiplex for at least one more.

Doc Soup Man: Did you try to get an audience or interview with Ali? Please describe what happened and your thoughts on this. Has Ali seen the film? Has he responded?

Bill Siegel: I had met Ali a few times during my year as a researcher on the Ali project where I met Leon in NYC. I learned a lot about humility simply from watching Ali hang out in the office there, doing magic tricks, pulling pranks and clearly enjoying every single person he encountered. I mean, it was clear to me that he loves being Muhammad Ali and he enjoys the effect he has on people, but to me then, it seemed like he enjoyed it as much because it made it easier for him to meet people as for any other reason. It is easy to see that being with people is something he clearly enjoys doing.

I really got from him, without him ever saying it, that he’s merely one guy and none of us are ever any more than that, but that every person is a mighty force worth knowing. I know that sounds so simple, but it was very formative for me, seeing Muhammad Ali demonstrate the difference between loving yourself versus being egotistical, by seeing him love everyone around him just as much.

Out of respect for Ali when I first set out to make the film, my first move was to seek his blessing. I wanted him to know that I was out to make a documentary about the most contentious and controversial period of his life that was real important to me. It took a long time, but I was able to meet with him and his current wife, Lonnie, about 6-8 years ago at their farm in Michigan. By then, Ali couldn’t verbalize very much, because of his Parkinson’s, but he could track entirely, still can to this day. And it was clear they both dug the idea, understood completely that it hadn’t been done and that it needed to be done. Lonnie looked me straight in the eye and said, “but it has to be an independent film, I don’t want my husband’s legacy whitewashed.”

Then in October 2012, I went to their home in Arizona and showed them both a fine cut. I wanted them to see where I’d gotten with the idea and I also hoped to get an interview with Lonnie for the film, ideally with some B-roll of Ali. I knew from the Michigan meeting that he was not going to be able to do a productive on-camera interview. Lonnie really doesn’t participate in media about Ali, unless it concerns Parkinson’s, research, fundraising or the disease as a whole. She also pointed out that she wasn’t there for the period of time focused on in the film, which is true. But she helped connect me to Hana, Ali’s daughter, who did do an interview that really helped land the film.

Of course, showing the fine cut to Lonnie and Muhammad was a nerve-wracking personal and professional thrill for me. I mostly watched Muhammad watch the cut and again could see he was tracking entirely, reacting with visceral facial expressions and digging the film. That is easy to say though, because I also know that Ali likes to do nothing more than watch or read stuff about Ali. In a sense, he’s the easiest audience member to please.

Last October, Lonnie came and saw the finished film at the Muhammad Ali Center in Louisville. I sat next to her in the front row. When the film ended, she stood right up and I thought, “Wow, she is out of here!” But then I slowly realized that she was participating in a standing ovation that the audience gave the film. That was incredible, especially because I was there with Justine Nagan, executive director of Kartemquin, Rachel Pikelny, producer of the film, and Aaron Wickenden, who did a masterful job editing it. Lonnie stayed for the Q&A and even asked a question. The whole thing was, as Gordon Davidson says in the film, “a big time howdy.”

Doc Soup Man: There appears to be what I’d call a benign representation of the Louisville Sponsor Group? I’m just guessing here—are there those who are more critical or skeptical of the group and its relationship with Ali?

Bill Siegel: I’d call it an honest representation of them, but I think I know what you mean. After all, on the surface of it, those guys are out of central casting. Southern white millionaires, gentlemen sportsmen, “capitalists” as Gordon Davidson says, representing bourbon, media, manufacturing, horses. I mean clearly these guys were used to getting their way. So you’d have to think that in segregated Louisville they must have exploited the hell out of hometown hero, Cassius Clay.

But my research shows otherwise, even Captain Sam, from the Nation of Islam, says they treated Clay (and later Ali) fairly. The Sponsoring Group was on the doorstep of history, but they had no idea where that door led when they first signed him. To me, they are a signpost for a kind of age of innocence that ends during their “sponsorship.” Surely, they must have had their minds blown when Cassius becomes Muhammad, announces he’s a Muslim, and then refuses to go to Vietnam. They were not alone in that experience, but they were intimately involved.