By Noel Murray

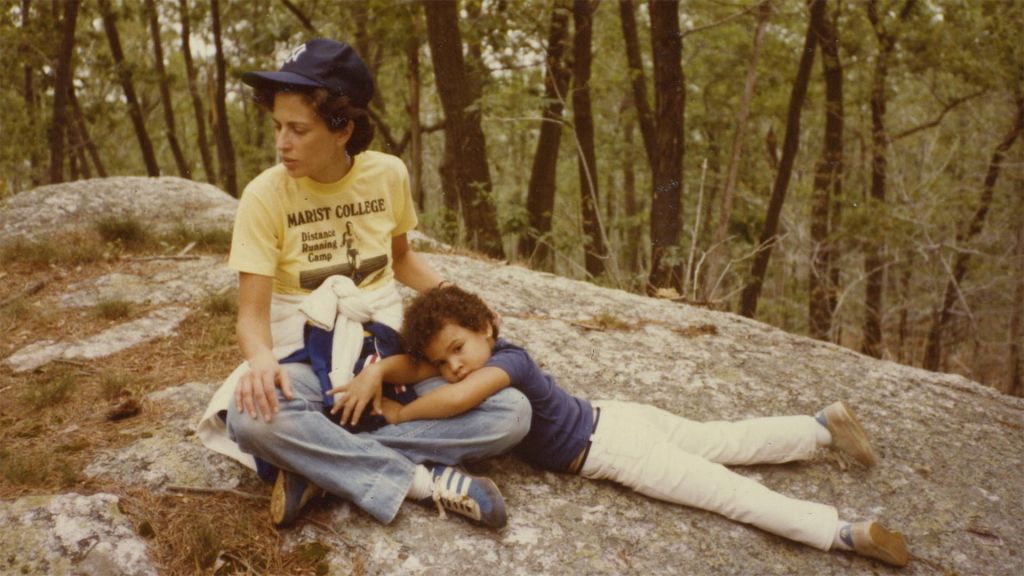

When Lacey Schwartz applied to Georgetown at age 18, she left the “racial identity” box unchecked, but did submit a photograph, and not long after she was accepted at the university, she was invited to join the black student association. The problem? Schwartz had been raised in a white Jewish household, by a mother who told her that her darker skin and kinky hair were due to her dad’s roots in Sicily. After a few months in college, Schwartz learned the truth: that she was the product of a tryst between her mother and an African American man.

Schwartz’s documentary Little White Lie is about more than just her family’s biggest secret. The film is a highly personal inquiry into the construction of racial identity, considering how others’ perceptions change depending on who they believe a person to be. But a big part of the appeal of Little White Lie is tied to its hook, because there’s something inherently dramatic in the story of an individual discovering that everything she thought she knew about her life was wrong.

The nine documentaries and feature films below offer a few more examples of how moviemakers have handled similar excursions into the sometimes-dark, sometimes-tangled roots of family trees.

The Melting Pot

Secrets & Lies (1996): Longtime movie buffs may read the description of Little White Lie and think immediately of Mike Leigh’s 1996 drama Secrets & Lies, which became one the British filmmaker’s biggest hits worldwide (and the recipient of five Oscar nominations, including one for Best Picture). A subtle study of race and class in the UK, Secrets & Lies has Marianne Jean-Baptiste playing a successful young black optometrist named Hortense, who goes searching for her birth mother, working-class wreck Cynthia Purley (played by Brenda Blethyn) who’s been sponging off her kindly younger brother Maurice (Timothy Spall). Leigh’s choice of profession for Hortense is no accident. When she arrives in the Purley’s lives, she helps them to see how they’ve been taking each other for granted, and hiding their true feelings. This is an often-intense film, but with an ultimately positive take on ripping open old wounds so they can heal properly.

In the clip below, Leigh talks a little about how he applied his usual improvisational methods of developing a story to make the inter-family dynamics in Secrets & Lies more potent.

A Family Thing (1996): Though it lacks the arthouse credibility of Secrets & Lies, the Hollywood melodrama A Family Thing does feature superb lead performances by Robert Duvall and James Earl Jones. The two play, respectively, an aging southerner and an aging Chicagoan, who discover that they’re half-brothers, and are subsequently forced to confront their biases and grudges by their elderly aunt (played by Irma P. Hall). The situation’s contrived, but the script by Tom Epperson and Billy Bob Thornton — whose Sling Blade would be released a few months later — still comes across as a lot more sensitive about the hard barriers between races in America than most feel-good fare will acknowledge. And as the two men learn about each other, they begin to understand more about the parts of their lives that have always seemed incomplete.

Lone Star (1996): Whatever it was that was in the air in 1996 also infected stalwart indie writer-director John Sayles, whose best and most popular film Lone Star has its own fascination with complicated racial and family histories. While investigating a murder mystery, a Texas border town sheriff (played by Chris Cooper) dredges up some truths that the locals would prefer to forget, about violence, payoffs, and secret deals between the leaders of the black, white, and Mexican communities. Sayles’ films tend to unfold like novels, all the way to their endings — he’s one of the best “enders” in independent cinema — and Lone Star’s no different, with a rich narrative that culminates in a shocking revelation about the hero’s father, suggesting an even deeper meaning to the movie’s story of race relations at the edge of America.

The Siskel & Ebert review below praises Sayles’ finely wrought, thoughtful script:

Into the Darkness

Capturing the Friedmans (2003): Long before The Jinx, documentarian Andrew Jarecki proved his true-crime bona fides with this haunting, harrowing film, about a family torn apart in the late 1980s when its patriarch is arrested for buying child pornography. As the criminal case played out, with ever-more-horrifying charges filed, various Friedman family members shot home movies of their increasingly bizarre everyday life. Jarecki assembles these — alongside some interviews from decades later — into an unsettling account of how the stain of one man’s guilt spreads across one seemingly happy, well-off Long Island family, causing them to question their own memories and their sense of self.

The Celebration (1998): A magnificent fusion of form and content, Thomas Vinterberg’s searing drama takes the style of the upstart Danish film movement “Dogme 95” — which insisted on handheld cameras and natural light — and applies it to the story of an embittered grown son who’s determined to use the occasion of his father’s 60th birthday party to reveal the old man’s long history of sexual abuse. The truth catches most — but not all — of the family by surprise, and for the rest of the weekend, the clan first stubbornly denies and then comes to accept that their leader is a pathetic monster. Vinterberg captures these changes in jittery, stark images that make everyone appear all the more exposed.

Ida (2013): An unexpected hit — and Oscar-winner — writer-director Pawel Pawlikowski’s gorgeous-looking black-and-white period-piece follows what happens to a novice nun named Anna (played by Agata Kulesza) after she learns that her real name is Ida Lebenstein, and that she’s the daughter of murdered Jews. Ida works as both a mini-history of a changing Poland from the 1940s to the 1960s and as a coming-of-age story for a woman who’s spent most of her life in an environment that discourages individuality. As she discovers her family history and experiments with sensual pleasure, Anna/Ida asks herself the question that so many of the men and women in these films do: “Who are you?”

Journey through the Past

Daughter from Danang (2002): Unlike Lacey Schwartz, the Tennessee-raised Heidi Bub always knew the basics of her genealogy: that she was the daughter of a Vietnamese woman and an American soldier, and that she was sent to the U.S. to be adopted when she was six, due to the sociopolitical turmoil in her homeland. In Daughter from Danang, this polite middle-aged southern lady decides to visit her birth mother back in Vietnam, but quickly becomes overwhelmed by the poverty, and by the assumption that now that she’s come home, she’s going to become her mom’s financial support. A lot of stories about adopted kids have heartwarming conclusions, but Heidi’s saga is more of a nightmare, as she discovers cultural chasms too wide to be bridged by blood alone.

My Architect (2003): The rare first-person documentary that’s also elegantly conceived, Nathaniel Kahn’s My Architect is his attempt to understand the choices made by his absentee father, Louis Kahn, an accomplished artist with a disastrous personal life. The younger Kahn doesn’t uncover the kind of sordid details that some filmmakers have when they’ve dug into their family dirt, but he does think about whether he, his mom, and his half-siblings were all some kind of necessary sacrifice that Louis Kahn had to make to design such beautiful buildings.

In the TED Talk below, Nathaniel Kahn follows up on his documentary with more thoughts on how and why he made it:

Stories We Tell (2012): The documentary that may have the most in common with Little White Lie started as kind of a lark for actress-director Sarah Polley, who looks at the life and loves of her late mother and considers the rumors that she — Sarah — was the product of infidelity. The more Polley explores, the more unpleasant truths she has to face; and the more she realizes that she’s breaking the heart of the man she’s always known as her dad. Stories We Tell means to be a meditation of sorts on how families mythologize themselves, sometimes at the expense of honesty. But in a way the film’s more philosophical elements are a defensive mechanism, keeping Polley at arms’ length from questions about marriage and genetics that she’s still nervous about answering.

Noel Murray is a freelance writer who contributes regularly to The Dissolve, The A.V. Club, The Los Angeles Times, and Rolling Stone. He lives in Arkansas with his wife, two children, and a TV that is never off.