By Kristal Sotomayor

In order to understand the rich history of criminal reform work, up through the vivid stories of crime and punishment presented in the docuseries Philly D.A., it is important to recognize Philadelphia’s origin story, as it were. This is by no means meant to reflect the entirety of Philadelphia’s complex history around criminal justice, but think of it as a primer on pivotal moments that lead to where we are now.

First, we’ll go way back because these stories, too, are key touchstones in the Keystone State.

Philadelphia Political Activism Goes Way Back

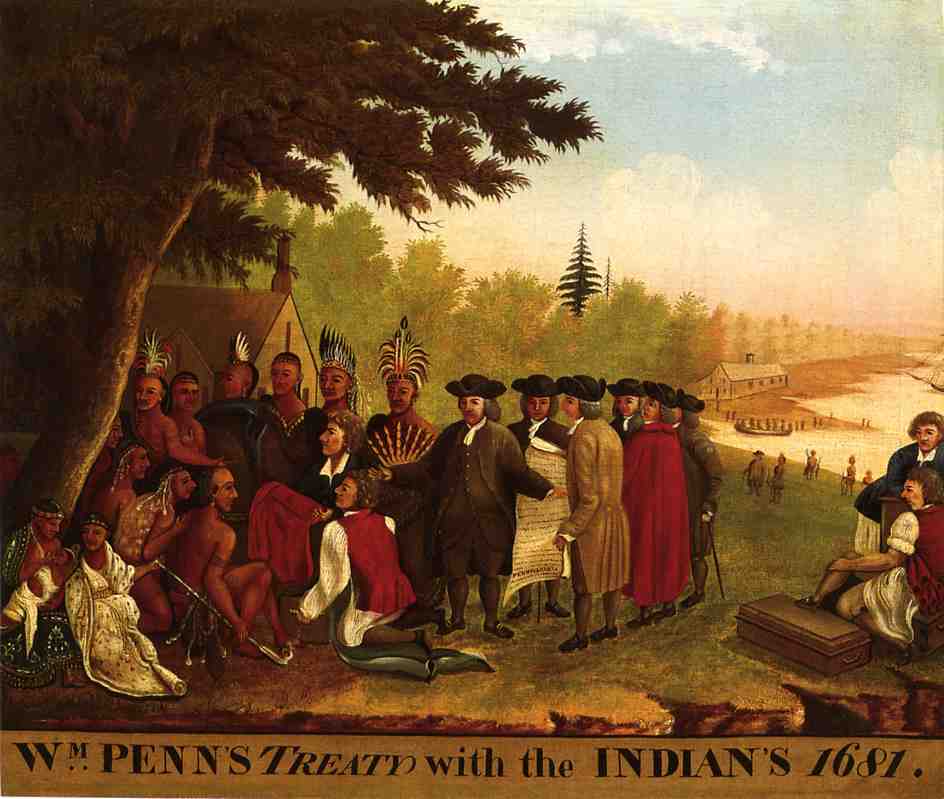

The territory currently known as Philadelphia is on the ancestral land of the Lenni-Lenape indigenous people. It is estimated that the Lenape people occupied the area for almost 10,000 years prior to European colonization. In 1681, William Penn was granted a charter by King Charles II of England to colonize the land and form the colony of Pennsylvania. A year later, Penn arrived in what would become Philadelphia, and in 1683, the Lenape people signed their first treaty with the Quaker pacifist.

Chet Brooks, a member and historian of the Lenape tribe, referred to it as “the treaty that was never ratified, but never broken.” While Penn kept to the commitments outlined in the treaty, his son, Thomas tricked the Lenape into giving away their land, and the tribe moved West in what became known as the Delaware Westward Trek. Most of the 15,000-20,000 Lenape people there did not survive the trek.

The Treaty of Penn with the Indians 1681, Edward Hicks, c. 1840. (public domain)

William Penn coined the name Philadelphia, derived from the Greek meaning “City of Brotherly Love” (a phrase still synonymous with the city name). It was home to the Quakers, a Christian denomination who worked (in their words) “actively to make this a better world.” From the founding of the colony, there were tensions over slavery, particularly among the Quakers. In 1684, the slave-carrying ship Isabella arrived in Philadelphia with hundreds of enslaved African people. This lead to the 1688 Germantown Petition Against Slavery which was “drafted by Francis Daniel Pastorius, a young German attorney and three other Quakers living in Germantown, Pennsylvania (now part of Philadelphia) on behalf of the Germantown Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends,” who saw that slavery seemed to clearly go against the Golden Rule, “do unto others as you would have them do unto you.”

The petition is cited as the first protest against the enslavement of African people by a religious group in the colonies.

Philadelphia and Abolition

In the 1770s, Philadelphia became the center of the American Revolution as the site of the First and Second Continental Congresses as well as the signing of the U.S. Declaration of Independence and the writing of the U.S. Constitution. While the American Revolution did not liberate enslaved Africans living in the U.S. colonies, Philadelphia has a deep history of abolition. In 1775, Thomas Paine author of “Common Sense,” an essay advocating for American independence, penned the essay “African Slavery in America,” in which he called slavery an “outrage against Humanity and Justice.”

1688 Germantown petition against slavery, on parchment paper (from public domain)

A month after the essay, the first American abolition society was founded in Philadelphia and called The Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage, later renamed the equally lengthy but specific: Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage in 1784.

In 1780, the Pennsylvania General Assembly passed the Gradual Abolition Act which was the “first extensive abolition legislation in the western hemisphere. The act gradually emancipated enslaved people without making slavery immediately illegal.”

Notably, members of the U.S. Congress, with headquarters in Philadelphia, were exempt from this edict.

While these steps did not end slavery, the impact of the abolitionist movement in Philadelphia has marked the city’s history.

During the 1800s, Philadelphia became central to the Underground Railroad which helped free enslaved African people. With a large free Black community, the city aided fugitive slaves and founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AMEC), which was the first independent Black denomination of the Episcopal Church.

According to the AMEC website, the church “grew out of the Free African Society (FAS) which Richard Allen, Absalom Jones, and others established in Philadelphia in 1787.” The Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, located at 6th and Lombard Streets, “stands on the oldest parcel of land continuously owned by African Americans in the United States.”

Mother Bethel A.M.E. Church in the Society Hill neighborhood of Philadelphia (Wikimedia Creative Commons photo)

With support from allies, other anti-slavery organizations formed in Philadelphia throughout the 1800s. In fact, the name of the famous “Liberty Bell” was given by abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison from the poem The Liberty Bell in 1844, which his publication The Liberator reprinted from a Boston abolitionist pamphlet.

The line “Ring it, til the slave be free” was adopted by abolitionists as a symbol of freedom.

The Pennsylvania System & Eastern State Penitentiary

Criminal justice in the colony was a stark contrast to England where death was the typical punishment. In the 1680s, William Penn brought his Quaker beliefs into the foundations of Philadelphia law and order. According to The Smithsonian Magazine, “Penn relied on imprisonment with hard labor and fines as the treatment for most crimes, while death remained the penalty only for murder.” When Penn passed away in 1718, the Quaker system of criminal punishment was replaced with “jails simply [as] detention centers for prisoners as they awaited some form of corporal or capital punishment.”

Walnut Street Prison, Pennsylvania Historical Marker, Philadelphia (October 2014). Photo: Morris Levin; Creative Commons.

Dr. Benjamin Rush, an abolitionist and the “father of American psychiatry,” was concerned with the overcrowding of the Walnut Street Jail, situated directly behind Independence Hall. Rush, who had the ear of Benjamin Franklin and other contemporaries, developed the “Pennsylvania System” and the institution of the penitentiary. He believed that the “moral disease” of crime could only be treated when “prisoners could meditate on their crimes, experience spiritual remorse and undergo rehabilitation.”

These ideas resulted in changes to the operation of the Walnut Street Jail including separating incarcerated people by sex and crime, the installment of vocational workshops, and the abolition of abusive behavior within the prisons. The Pennsylvania System reformed the criminal punishment of the time.

In 1822, construction began on the Eastern State Penitentiary in response to overcrowding in the Walnut Street Jail. The technologically innovative design of the penitentiary was created by John Haviland, a British architect. The Eastern State Penitentiary was constructed with “seven wings of individual cell blocks radiating from a central hub.” It opened in 1829 and had, according to Smithsonian magazine, “central heating, flush toilets, and shower baths in each private cell, the penitentiary boasted luxuries that not even President Andrew Jackson could enjoy at the White House.”

The first inmate at the penitentiary was farmer Charles Williams, sentenced to two years for theft. In order to protect the anonymity of the inmate, an integral part of the rehabilitation and reintegration process, Williams was escorted to the prison with a hood covering his face. In addition, the inability to see the prison ensured that it would be impossible to escape because Williams could not see the prison beyond his cell.

As an inmate, the only interactions with guards were conducted through a small hole used for feeding. Inmates were expected to live in complete isolation and were only allowed a Bible as personal possession with chores to fill their time.

The isolation and heavy monitoring of the Pennsylvania System would prove to be inhumane and unattainable with the technology of the time.

Eastern State Penitentiary stopped using the Pennsylvania System in 1913. Instead, they began to embrace shared cells and allowed inmates to work together and play sports. The penitentiary held approximately 75,000 people over the years of operation including notable inmates like bankrobber “Slick Willie” Sutton and gangster Al “Scarface” Capone. After 142 years of operation, the penitentiary was closed by the state of Pennsylvania in 1971.

Al Capone’s cell at Eastern State Penitentiary, 2007 photo. (Creative Commons image; 2007)

The Wild 20th Century

The 20th century was marked by a period of corruption within the Philadelphia governmental system such as mismanagement of funds and political favoritism. The impact of the scandals and allegations of fraud led to a wave of strict, law-and-order government officials in the D.A. and mayoral offices.

In 1951, however, progressive Philadelphia District Attorney Richardson Dilworth, once of Pittsburgh, was elected. Dilworth advanced civil rights by hiring Black lawyers and assigning them major cases. In addition, Philly Mag reports, “when a racist Common Pleas judge complained about having to hear arguments from Blacks, Dilworth made sure to pack that judge’s courtroom with his best Black assistant district attorneys.

“His private law firm was the first major firm in the city to have a Jewish partner. And he hired the brilliant Black lawyer William T. Coleman, who had clerked for two Supreme Court justices but couldn’t land an interview at any other Philly firm.”

During his time as D.A., the city developed the planning department, a housing department, and the Redevelopment Authority. His work included the strengthening of city planning to support the needs of the residents. In the 1970s, Coleman became Gerald Ford’s Secretary of Transportation and would later be awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom for the number of racial barriers he broke along the way.

https://twitter.com/independentlens/status/1383465278235836416?s=21

Columbia Avenue Riot

In the 1960s, the United States was in the throes of the Civil Rights Movement, an era marked by reckoning for racial equality and the rise of the Black Power movement. Throughout the country, there were protests and demonstrations to disrupt segregation and inequality. In late August of 1964, Philadelphia experienced one of the first “race riots” of the Civil Rights era.

The Philadelphia race riot, also known as the Columbia Avenue Riot, began on August 28 when Odessa Bradford, a Black woman, was stuck in her stalled car at 23rd Street and Columbia Avenue. Bradford refused to exit her immobile vehicle and got in an argument with two police officers—one Black and one white. In the end, Bradford was forcibly removed from her vehicle, and a bystander who tried to stop the police was arrested. This incident led to rumors being spread about a pregnant Black woman being murdered by white police offices.

Local news report, Philadelphia 1964:

For three days, angry residents looted and burned business in North Philadelphia on Columbia Avenue, mostly those run by white owners. With large crowds, the police withdrew from the area. Prominent Civil Rights leader Cecil B. Moore tried to help end the altercations. In the end, there were no deaths involved from the incident although 341 people were injured, 774 arrested and 225 stores were damaged or destroyed in the three days of rioting.

Frank Rizzo’s Reign

In the wake of governmental corruption, the civil rights movement and unrest due to racial inequality, the boisterous Frank Rizzo, a cop for 20 years, became the Philadelphia police commissioner from 1968 to 1971 and later mayor of Philadelphia from 1972 to 1980. Rizzo became a “symbol of white identity politics” appealing to white voters while largely ignoring Black neighborhoods during his campaigning efforts.

His political stances include being resistant to the desegregation of the Philadelphia school system, supporting ‘stop-and-frisk’ policing tactics, and working to prevent public housing initiatives. All of these efforts largely affected Philadelphia’s African American neighborhoods.

Frank Rizzo (at right) shows President Nixon around Independence Hall in Philadelphia, 1972. (Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Amongst the police, Rizzo’s nickname was “The General” because of his aggressive, tough-on-crime attitude. He is often compared, in retrospect, to President Donald Trump because of his outlandish statements and quick temper.

Rizzo infamously once said, “[The Black Panthers] should be strung up.” In 1970, he led a raid of The Black Panthers’ Philadelphia offices and strip-searched and posed leaders for local newspaper photographers. Throughout Rizzo’s career, his work was marked by his attacks of Black liberation groups.

A CBS News Special Report from 1971:

MOVE

In 1978, Mayor Rizzo engaged in a 15-month standoff with The MOVE Organization (MOVE), a group founded by John Africa that focused on animal advocacy and Black civil rights. The standoff ended with a shootout at the Powelton Village headquarters that led to the death of Police Officer James Rump. Although the cause of Officer Rump’s death is highly disputed, nine members of MOVE, named the “MOVE 9,” were all tried and convicted of life sentences as a group.

Emmett Fitzpatrick, Jr., who was the Philadelphia District Attorney at the time, received ethics-related complaints and was criticized for his sentence recommendations. A year after the shootout, the U.S. Department of Justice led a lawsuit charging Rizzo and other city officials for “allowing pervasive police abuse.” From the investigation, it was found that “from 1970 to 1978, the police shot and killed 162 people.”

From the film Let the Fire Burn. MOVE members and police during the 1978 confrontation outside MOVE headquarters.

In 1985, under Mayor Woodrow Wilson Goode Sr., the first African American mayor of Philadelphia, MOVE was once again targeted by law enforcement. On the evening of May 13, the Philadelphia police “dropped a satchel bomb, a demolition device typically used in combat, laced with Tovex and C-4 explosives” on MOVE’s new headquarters at 6221 Osage Avenue in West Philadelphia. It was known that the building was occupied by men, women, and children.

The building went up in flames, destroying 61 homes, killing 11 people (including the founder of MOVE and five children), and leaving over 250 residents homeless. Only two MOVE members survived: Ramona Africa (29 years old at the time) and Birdie Africa (13 at the time), later known as Michael Moses Ward. Jason Osder’s 2013 Independent Lens documentary Let the Fire Burn captures the tension between the Philadelphia police and MOVE leading to the tragic climax of the 1985 bombing.

More from The Guardian

The Philadelphia District Attorney at the time was Edward Gene “Ed” Rendell, who later became Mayor of Philadelphia in 1992 and then Pennsylvania Governor in 2003 as a Democrat. As district attorney, Rendell prosecuted MOVE members including the MOVE 9. On the MOVE bombing, Rendell states that he “regrets the severity of the sentences he pursued for those who were not leaders of the group.” Mayor Goode Sr. offered several apologies for the MOVE bombing although he maintains that his office did not know of the decision to drop the bomb. In May 2020, the Philadelphia City Council offered a public apology on the 35th anniversary of the MOVE bombing.

While Frank Rizzo left office in 1980, his influence on the Philadelphia Police Department is undeniable. According to 2015 Police Employee Data from Governing, Philadelphia had the fifth-highest police-officer-to-citizen ratio in the U.S. Philly Mag reported in 2015 that “whites are over-represented in Philadelphia’s police force by 20.4 percentage points.” Most recently, in 2020, the Innocence Project and the District Attorney’s Conviction Integrity Unit raised questions about the fabrication of evidence, planting of a weapon and arrest under false pretense. The most recent wave of criminal justice reform and activism has been directly influenced by Philadelphia’s history of slave abolition and the search for liberty.

Mumia Abu-Jamal and the Death Penalty

In 1982, D.A. Rendell presided over the prosecution of Black political activist and journalist Mumia Abu-Jamal, who was given a death sentence for allegedly murdering white Philadelphia police officer Daniel Faulkner. Abu-Jamal has since gained national press for his writings on the criminal justice system while on death row, including the published books Live From Death Row, All Things Censored, Death Blossoms: Reflections from a Prisoner of Conscience, and We Want Freedom: A Life in the Black Panther Party.

In 2011, after many appeals, prosecutors in Philadelphia reversed his death sentence to that of life in prison without the possibility of parole. Seth Williams, the district attorney at that time, maintained that Abu-Jamal was guilty but the decision to reverse the death sentence was because it was “time to put the case to rest.”

While working to uncover wrongdoing by previous D.A.s, in December 2018, Krasner’s office found six boxes of documents containing new evidence of misconduct in Abu-Jamal’s case; evidence that prosecutors failed to provide Abu-Jamal’s lawyers for decades. As Linn Washington Jr. and David Lindorff put it in a WHYY op/ed, “Withholding such items defines prosecutorial misconduct.”

Despite the new evidence and Krasner’s record overturning convictions, his office defends the witness testimony in Abu-Jamal’s alleged shooting of officer Faulkner. The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, in February 2020, “ordered a highly unusual investigation into Krasner’s handling of Abu-Jamal’s case, which was demanded by avowed opponents of the incarcerated former journalist,” but in December the Court ruled Krasner’s office can continue handling appeals for the case.

1980s – 2020s Philadelphia District Attorneys and the Death Penalty

District Attorney Ronald D. Castille took office in 1986 and later served on the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania from 1994 to 2014 and as Chief Justice from 2008 to 2014. During his time as D.A., he frequently recommended the death penalty. In 1984, Castille personally sought the death penalty in the case of Terry Williams, who was charged with murder. The sentence was overturned by a Common Pleas Court judge. However, in 2014, Castille served as a state Supreme Court justice when they came to the unanimous decision to reinstate Williams’ death sentence.

Two years later, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that “former Pennsylvania Chief Justice Ronald D. Castille was wrong to participate in an appeal from a death-row inmate whose prosecution he oversaw nearly three decades before.”

Following Castille’s terms as District Attorney, Lynne Marsha Abraham served as D.A. from 1991 to 2010. She was the first woman to hold that office and was the longest-serving D.A. in the history of Philadelphia. Abraham earned the nicknames “America’s Deadliest D.A.” and “Queen of Death” because of what many perceived to be her excessive use of the death penalty.

Judges’ seats inside Pennsylvania Supreme Court in Harrisburg (Creative Commons)

According to the New York Times, “Abraham believes in the death penalty, but also supports it because her constituents do. To her, it doesn’t offer society control over crime—she doesn’t believe it’s a deterrent—but instead gives the feeling of control demanded by a city in decay.”

The death penalty was revived in Pennsylvania in 1978 with three Philadelphia D.A.s who were strong supporters of capital punishment. Abraham, however, prosecuted far more death penalty cases than any other Philadelphia D.A. In a 2016 Harvard University report, Abraham was found to be the fourth “deadliest” prosecutor in the country. While she served as District Attorney, Abraham obtained approximately 108 death sentences, which disproportionately affected Black communities. The New York Times cites “high rates of crime and drug addiction” as the reason why law-and-order politicians such as Frank Rizzo and Abraham come into office. On February 13, 2015, Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf announced the moratorium on the death penalty in the state.

Legacy of Crime and Punishment—and Reform

With a legacy of slavery abolition and criminal justice reform, the 20th and early 21st centuries of Philadelphia history have also been marked by corruption and heavy criminal punishment. And decades of racial inequality and targeting of Black residents by the Philadelphia Police Department and District Attorney’s Office framed the 2017 District Attorney’s race.

Larry Krasner won the election and took office in 2018, as covered in the eight-episode Philly D.A. docuseries. The series portrays Philadelphia as a microcosm for the complex issues of criminal justice reform in the country as a whole. With a platform of police reform and reducing incarceration, Krasner has been dubbed a “Progressive D.A.” but the jury is still out. The future of criminal punishment in Philadelphia and the nation beyond is still a complicated one, forever evolving it seems.

Kristal Sotomayor is a bilingual Latinx filmmaker, festival programmer, and freelance journalist based in Philadelphia. They serve as the Programming Director for the Philadelphia Latino Film Festival and Co-Founder of ¡Presente! Media.