A little over a year ago, filmmaker Scott Kirschenbaum, whose deeply moving film You’re Looking at Me Like I Live Here and I Don’t aired on Independent Lens, wrote a piece for Huffington Post on the unforgettable experience of shooting the documentary in an Alzheimer’s care unit. In honor of both Alzheimer’s Awareness Month and that the film will be available to watch for free online this week on PBS.org through September 25, we’re reprising Scott’s original piece as well as including an update from the filmmaker.

Additionally, the film will be screening for free at the New York Public Library this Thursday, September 19th, at 3:30 p.m., followed by a panel discussion exploring the intersection of medical research in the field, the arts, social services, and the quality of life of individuals living with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. The director will be in attendance. More details can be found here.

Here’s Kirschenbaum’s original piece for Huffington Post, followed by an update.

In the fall of 2008, I wrote a screenplay I intended to film entirely in an Alzheimer’s unit. After many weeks of rehearsals, I arrived at a troubling realization: I was not just making a challenging film — I was making the wrong film.

Writing a fictional Alzheimer’s narrative — creating a neat and orderly plot whose course I could control, from a disease by nature chaotic and nonlinear — was impossible. In the way that a son or daughter doesn’t know exactly what to expect during a visit with a parent who has Alzheimer’s, it’s inconceivable (some might even say ridiculous) for a screenwriter to map out the trajectory of a scene in an Alzheimer’s unit, and expect it to play itself out in a manner remotely resembling what was written.

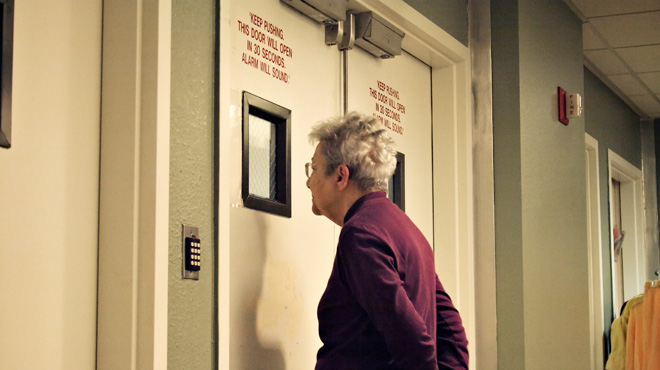

Other than the loose structure provided by a schedule of daily activities — a parachute toss, the hair salon, an oldies sing-a-long — life in an Alzheimer’s unit does not follow the logic of the real world. It is founded upon the incidental and accidental, a string of interactions and experiences that digress unpredictably, omnidirectionally and constantly turn back on themselves. The Alzheimer’s unit almost never adheres to the continuity of the linear narratives that we enjoy on a daily basis — or that screenplays require.

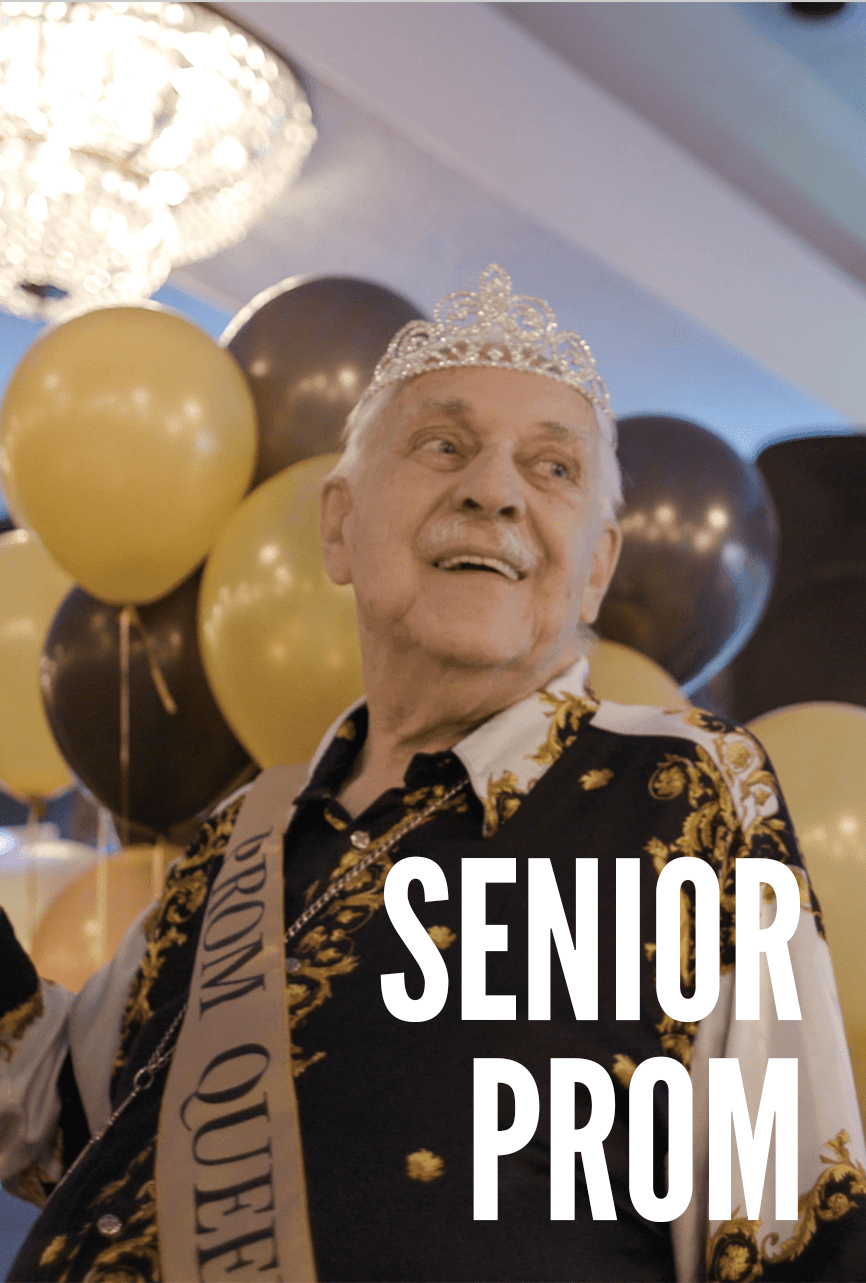

The first time I visited the Traditions Alzheimer’s Unit in Danville, Calif., I was greeted at the door by Lee Gorewitz, a spry septuagenarian in a baby blue jogging suit. With the exuberance of a cruise director, Lee presented herself as a staff member, took my hand and gave me a tour, during which she delivered a soliloquy unlike anything I had ever heard before: for well over a minute she prattled on about purses, windows and gardens, before she eventually locked eyes with me and said: “I hear the song in my ears, and I think they don’t love me anymore.”

From this spontaneous word-salad came two things that forever altered my film project; I realized Lee was not staff, but a resident. And, I decided, her presence in the unit was reason enough to throw away that screenplay I’d just written.

For the next six months, I visited Lee with the hope of making a documentary that would capture her inner universe: the discord and frustration, the communication breakdown and uninhibited behavior everyone speaks of when they speak of Alzheimer’s — and the unusually poetic candor it can distill. Reflecting on her birthplace, Lee would say, “Brooklyn, it’s right behind you.” Considering love: “That’s a damn good thing to work with.” Regarding her deceased husband: “How do I even say it? The air — was very good.”

Like many in an Alzheimer’s unit, for Lee every day is an odyssey: wandering to and fro with no destination in particular, on a quest for something that she can neither articulate nor comprehend. Having advanced Alzheimer’s was once described to me by a neuroscientist as akin to waking up in the middle of hinterland Russia, alone, not knowing a lick of the local language, not knowing how you got there and being expected to act like it was home.

Due to that constant sense of disorientation, in the span of minutes Lee could morph from pensive thinker to gregarious helper, from bubbly mover-and-shaker to morose and sometimes cruel instigator. When in good spirits, she consoled heartbroken women, kissed caregivers and shook a tail-feather even after the music had stopped. And with no realistic option for leaving, Lee also gave in to frustration: She argued with her tablemate at lunch, kicked a bouncy ball at a frail man’s legs and unapologetically told a sickly woman that she is going to die.

My time with Lee, and her struggle, left me utterly confounded. Who should say Lee’s fragmented reality is any less valid than my own?

Composer John Cage once wrote, “The first question I ask myself when something doesn’t seem to be beautiful is why do I think it’s not beautiful. And very shortly you discover that there is no reason.” A shift happened for me when I started to embrace the sublime chaos of Lee’s world. Spending time with her became not about remorsing on what will never be, her past (most of which she cannot remember) — nor was it about analyzing the tragedy of her plight. It became about letting Lee tell her own story, one unfolding in the context of a cruel, debilitating disease. And it became about learning that there was no reason not to let that story seem beautiful.

In ways that are often painful and intense to the rest of us, Lee and others with Alzheimer’s stumble along a road we’re all traveling, trying — often desperately — to communicate something, anything, grasping for unanswerable riddles.

And until there’s a cure for Alzheimer’s, there’s one way, outside of medicine, to counter this disease, which we all have within our reach, whatever the road, whatever our relative agility at traversing it.

Empathy.

And now we follow up with Scott:

What’s happened since the film’s initial release?

Since this documentary was released on Independent Lens, countless colleges and public libraries in the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and England have begun using the film for educational purposes. It’s amazing at how far a reach this film has had, and it’s so nice to know people around the world continue to love and appreciate Lee Gorewitz.

September 13th marked the one-year anniversary of Lee’s passing in 2012. She was an incredible woman, so very full of exuberance and resilient, and continued to be a positive presence in her care facility until the very end.

Has your own personal experience with Alzheimer’s affected how you live your own life?

Invigorated by this filmmaking experience, I’ll continue to explore mental health issues with future film projects. This is a subject that is dear to me as any, and I hope to continue championing efforts to raise awareness around mental health issues.

What is the message you’d like audiences to take away from watching You’re Looking at Me…?

While making this film, I was regularly asked whether I find the subject matter depressing. Yes, this disease is terribly sad, but one of the enduring values of humanity is compassion, particularly with regard to our elders. If we sugarcoat or, worse yet, turn a blind eye to an important issue like Alzheimer’s because it makes us uncomfortable, we will never understand its complexities or come to appreciate the role memory, family, knowledge, music, and language continue to play in the lives of sufferers. Though those with Alzheimer’s might forget us, it seems unconscionable to send our elders off to nursing homes and forget them.

And what can people reading this do to help Alzheimer’s patients, caregivers, affected families and research — even on the smallest scale?

The absolute best way to learn about organizations and individuals doing work in this field would be to connect with us through twitter (@yourelooking) or our website (yourelookingatme.com). Over the years, we have cultivated some great relationships with organizations working in Alzheimer’s awareness and research, and try to be a consistent source for our community with the latest and most up to date developments on all things related to Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia.

Watch the film for free through September 25, 2013, by going here. And honor Alzheimer’s Action Day, too!