The first documentary to explore the role of photography in shaping the identity, aspirations, and social emergence of African Americans from slavery to the present, Through a Lens Darkly: Black Photographers and the Emergence of a People probes the recesses of American history through images that have been suppressed, forgotten, and lost. Thomas Allen Harris’s film visits the past through the lens of the present by visiting the works of current and historical African American photographers as well as archival images dating back to the Civil War era.

Harris — whose films and installations have been featured at prestigious film festivals as well as museums and galleries including the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Biennial, the Corcoran Gallery, Reina Sophia, and the London Institute of the Arts — talked to us about his own relationship with photography and what he hopes viewers will gain from seeing the film.

What’s your own family history with photographs and photography? How far back do your family photos go?

My maternal grandfather, Albert Sidney Johnson, Jr., was an amateur photographer who spent his life creating a vast treasure trove of images. Photography, like education, was his passion and he was obsessed with taking photographs of his family and extended family. Grandfather inculcated in all of the male members of the family the same zeal, including my brother and me, our cousins, and his own brother. It was like a special right of passage. He gave me my first camera when I was only six years old and even today I carry at least one camera with me at all times, just like he did.

For Albert, photography was a means of unifying our extended family, knitting together the disparate branches and providing a means to connect one generation with the next. And they weren’t just his images. My grandfather’s living room was a gallery; filled with the images of famous Black leaders as well as the images of our forbearers, interspersed with his own photos, and included precious photos bearing the imprints of legendary Harlem photographers James Van Der Zee and Austin Hansen. Like grandfather’s stories describing his great grandparents making their way out of slavery and building their lives into something despite the pervasive and crippling racial barriers they faced, the legacy of these photographic images proudly showed us who we were.

The images on the mantel place were from both my grandfather and grandmother’s archives and went back to the 1880s approximately. In researching this film, I found images of my family that went back even further… to the 1850s.

And did you have an interest in photography before embarking on this project?

I engaged with photography from elementary school through middle and high school in East Africa and the Bronx and began to formally study photography as a senior at Harvard College while majoring in Biology. I worked professionally as a photographer after that until I started producing television and independent films. It was during the time I was working as a photographer that I met Deborah Willis at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. She published my first photographs and curated my first shows.

How did you first come across Willis’s book Reflections in Black: A History of Black Photographers 1840 to the Present and what about it inspired you to make a film connected to it?

In 2003 Deborah Willis approached me about making a film interpretation of her groundbreaking book which detailed the history of African American photographers from the invention of photography to the present. My photographic work was included in the publication along with my brother artist/photographer Lyle Ashton Harris. I’d known Deb Willis as a young photographer/filmmaker just starting out and and our work around the African American archive had paralleled. For over 20 years, I’ve been mining my family and extended family archives in my films, so I was eager to delve into this project. What I did not know was this project would take me on a personal journey to understand why it was so important for Black photographers, both professional and vernacular, to make photographs. Indeed, through this journey I was to learn that it was a form of activism and a strategy for survival in America.

What was the most surprising revelation for you in putting Through a Lens together?

It was a ten year process. We built off the work that Deb Willis did initially, and then working with producer Ann Bennett we found images in many unlikely sources around the country with our research teams. We collected over 15,000 images this way and then with our community engagement project, Digital Diaspora Family Reunion Roadshow, we toured all over the eastern seaboard, from Atlanta up to Boston, encouraging people to rethink the educational value of their family photo albums through the act of sharing them (and their stories) with us and a live audience.

Through the Roadshow we collected another database of 6,000 images of African American families going back to the 1840s. And then the hard part of selecting the images to tell our story. It was important to us not to use images to illustrate (as they are traditionally used in docs), but to speak for themselves and push the narrative forward. An image speaks volumes — so with 950 images, we cover 170 years or so of American history through the lens of Black photographers and African American families.

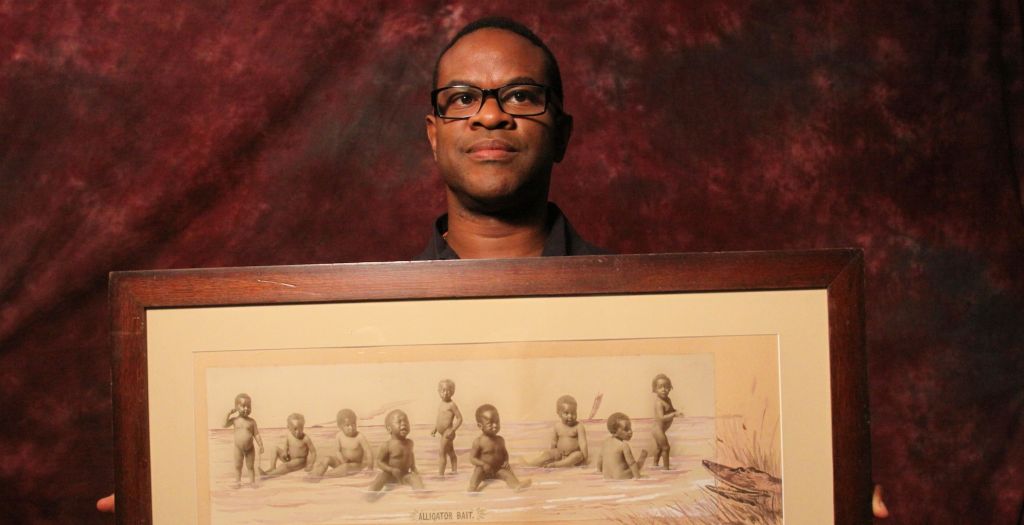

Some of the images from America’s past when it comes to depicting African Americans look pretty shockingly stereotypical to the modern eye. What can people learn from looking at these pictures?

The power of representation. Images shape popular culture’s view of what “Blackness” is and who “Black people” are – both in the images that are out there but also those hidden from view. At every critical juncture in the evolution of Black Americans, from slave to hip-hop artist, from sharecropper to President of the United States, from the urban housing project to Palm Beach, Black photographers have been there, showing the ordinary daily lives of a people who have been integral to making America what it is. As Deborah Willis notes, when you subtract the images of Black photographers, you also subtract the images of African American family. It is in this absence that stereotypical images proliferate.

What projects are you working on next?

I am working on a television show based around the film’s Digital Diaspora transmedia project, going around the country finding the hidden photographic archives in people’s closets.

I am also working on a narrative feature about an immigrant who comes to New York in search of a missing brother.

What do you hope people take away from seeing Through a Lens Darkly?

I want people to take away the importance of history, of knowing who we are and where we’re from. To experience a kind of Truth and Reconciliation through filling in, experiencing the joy and the pain as seen in these artists’ vision of the American family album. I want people to shoot with the camera instead of the gun!