What is the cost of feeling “safe” in American classrooms in an era when mass shootings have become more commonplace? The documentary Bulletproof takes a unique vérité approach in exploring and interrogating how we approach safety, intercutting between different high schools and their stressful danger drills, burgeoning school security industry expos that pitch bulletproof whiteboards to school board members, and talented creators who introduce eerie new protection technology like Kevlar hoodies.

Filmmaker, artist, and educator Todd Chandler channeled his experiences as a teacher into inspiration, resulting in Bulletproof. Named one of Filmmaker Magazine’s 25 New Faces of Independent Film in 2019, Chandler’s film work has explored American rituals, landscapes, and systems of power. Along with his time as a film teacher at Brooklyn College, he’s also worked with schools in making videos about contemporary issues. All these roads led to Bulletproof, a film that The Moveable Fest called “Brilliant…Invaluable…A smartly conceived look at the first generation of students to prepare for mass shootings and how fear of them has been commoditized.” The New York Times‘ Teo Bugbee called the film, “Dreamlike. Startling. An alarmed and alarming vision of safety.”

I talked to Chandler about that unusual, dreamlike approach—one which allows for the film’s power to sneak up on you—about the “normalization” of violence in America, and what he hopes audiences might take away from Bulletproof, in an answer inspired by poet Adrienne Rich.

Can you talk about how your own experience as a teacher inspired or led to telling this story?

In 2015, there was a mass shooting in Oregon. The next day I overheard a group of my Brooklyn College students talking about it before class. I put aside my plans and invited them to continue the conversation about lockdown drills, putting police in schools, and arming teachers. A few of the students that year were from the UK, and they kept remarking that the subject matter seemed so distinctly American to them.

This discussion stuck with me, and, later that year, I set out to make a film to map the paths of violence and fear in schools across America by examining the ways in which we try to prevent it.

And how did you first learn about the school shooting survival workshops that are shown in the film?

Also in 2015, I was talking with a friend whose brother is a former Navy SEAL. He mentioned that after many years, his brother had retired from the Navy and was now leading workshops in schools, training teachers and students how to survive school shootings. None of this was new, but at the time I didn’t have a real sense that there was an entire industry around school security.

You take a provocative, unique way of approaching the story of gun violence in American schools, which has been depicted in other documentaries but never quite like this. What inspired you to make the film artistically with this unique pastiche fly-on-the-wall approach?

There have been a number of films made about violence in schools, about specific incidents. I thought it might be illuminating to focus on the infrastructure, the culture, and the fear that lives in-between moments of crisis.

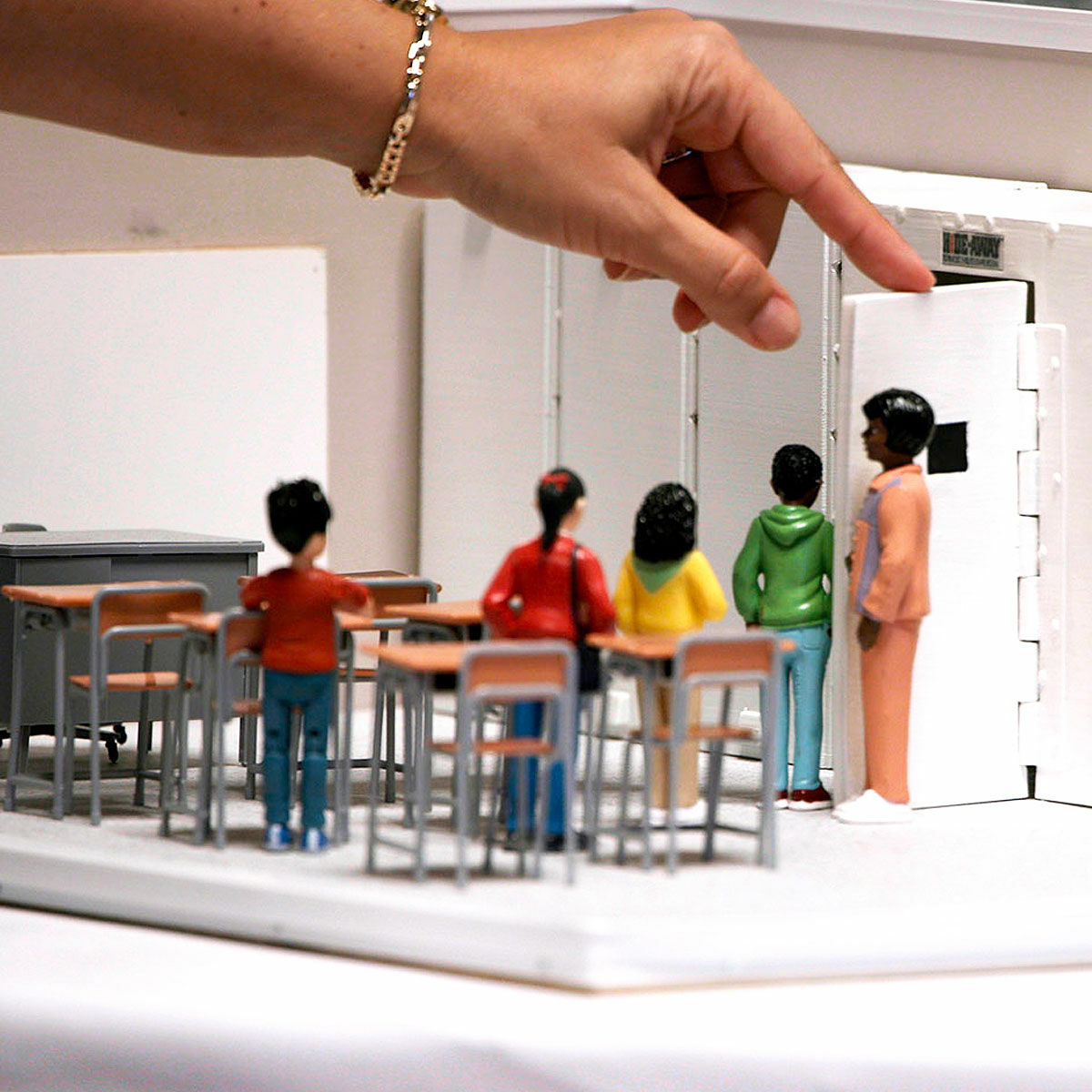

As I began to spend time in classrooms and gymnasiums, in trainings and at conferences across the United States, I was most drawn to the elements of ritual in what I was filming: a lockdown drill, basketball practice, teachers stepping up to the line at a shooting range, a dry run of the homecoming parade, a sales pitch at a school safety trade show. There’s choreography to each of these activities. They’re all rehearsals or preparations. Performances to ward off violence, failure, or to hold at bay the fear of either, or both.

Filmmaker Todd Chandler

If one can glean a measure of insight about a society’s character by looking at its rituals, perhaps an examination of the practices, protocols, and procedures that take place in and around schools might illuminate something about American culture. That “something” might change, depending on who is viewing, and where they are standing.

A really eerie thing about Bulletproof is how you don’t really have any establishing shots, you thrust viewers into each location in a way that can be disorienting but powerful. Can you talk about putting the film together that way?

It was a very intentional choice to not have conventional establishing shots or location titles. I wanted to avoid specificity because I think it’s easy to then ascribe a kind of causality to a place or group of people and then write it off (“Of course that’s happening in…Texas,” for example).

I wanted audiences to be clear when we were in a suburb, a city, or a rural area, and there are plenty of more specific contextual clues, but I didn’t foreground the exact locations because I wanted the film to open up into a broader set of social, political, and economic forces that are shaping the culture of schools across the United States.

How was it emotionally to film these intense moments in schools, places that are supposed to be “safe havens” for kids?

Not every location was intense, but in the moments that were, I learned to block it out by focusing on the frame and making sure we were recording the images in a way that was going to work for the film. But often, immediately after driving away from a day of filming, our entire tiny crew would collectively let out an enormous sigh, and then debrief on the events of the day.

It was surreal at first and then started to feel more normal, which was also a little disturbing.

The Variety review of Bulletproof called it “a keenly observational film that depicts the day-to-day normalization of the unspeakable.” I was wondering if you could talk about that aspect, “the normalization” of how this country tries to address mass school shootings, and how much were you conscious of this mindset before you started making this documentary?

At first, I was thinking a lot about the normalization of mass violence through the ubiquity of these prevention strategies. As the film expanded to be more about ritual and rehearsal, I began to think about the trajectory of that normalization—what has long been, and what is fast becoming, normal. I think there is a relationship between the performances that happen at a homecoming parade or football practice and the performances on the firing line or in the active shooter drills.

What do you think the “cost” of feeling safe is in America?

I think one needs to define safety before one can assess its costs. In Bulletproof, we meet a lot of people who define safety as preventing gun violence. But that definition of safety, and the urgency of the mission to achieve it, can eclipse what underlies it—a culture of fear and violence that leads to mass shootings, but even more often leads to suicide, to sexual violence, to racialized violence, to repression, alienation, and addiction.

What kind of change is needed to engender a deep, all-embracing safety, and what does that cost? Is it the cost of universal health care, of reparations, of free college tuition, of medical and college debt relief, of truly affordable housing, of a living minimum wage, of abolishing prisons and police, of creating substantive infrastructural change to combat climate change?

Has anyone portrayed in the film had any interesting reactions that they shared with you after they watched it?

One situation that stands out is when producer Danielle Varga and I flew halfway across the country to show one of the participants the film in advance of its release. This is someone whose political and social views are significantly different from mine. When we sat down together, they admitted that in hindsight they were concerned about how much they had trusted us and were anxious about how they might be represented in the film. But after watching it they said that they felt very fairly represented.

This felt like a real success to me, because while Bulletproof certainly has a critical point of view, I tried to articulate that through its cinematography and editing, [and] through juxtaposition and contrast, rather than pushing an explicit and dualistic agenda in which there are clear good guys and bad guys.

What would you like PBS audiences to take away from watching Bulletproof?

In the poet Adrienne Rich’s collection An Atlas of the Difficult World, there is a poem that begins with a declaration: “Here is a map of our country.” She goes on to describe an array of forces, archetypes, and landmarks in an evocative survey of the beauty and horror of the United States. But in the end, the poem’s narrator concludes, “I promised to show you a map you say but this is a mural.” The distinction is small but important.

Maps render an existing landscape at scale, showing us, with some accuracy, the contours of the earth, orienting us as travelers. A mural transforms the existing landscape. It is open to interpretation, a piece of art that prompts us to see our surroundings in new ways.

My intention is for Bulletproof to be both a map and a mural. The film is, in part, a fragmented survey of the landscape of safety and security across the United States. And while offering this map, Bulletproof also reframes and refracts the very landscape it documents to pose a set of questions.

What are the relationships between the homecoming parade and teacher firearms training, the sales pitch, and the lockdown drill? What might these rituals reflect back at us?

My hope is that the film might transcend immediate causes of and responses to mass shootings, to provoke a deeper reflection on the array of forces that have shaped the culture of fear and violence in the United States since its inception.