By Bedatri D. Choudhury

Chol Soo Lee was a Korean American immigrant wrongfully convicted in 1974 of murdering a Chinatown gang leader in San Francisco. After a decade of being incarcerated, serving four of those ten years on death row, Lee was acquitted following a massive public campaign that raised more than $120,000 for his appeals. Lee passed away in 2014, after a lifetime struggling against the many failed machineries of the State, without an apology or compensation.

The story of his life, the public movement it inspired, and his complicated later years gets told in Free Chol Soo Lee, co-directed and produced by Julie Ha and Eugene Yi. It highlights how Lee became the sacrificial lamb at the hands of not just the State’s prison industrial complex but also its failed mental healthcare, education, immigration, and fostering systems.

Award-winning journalist Ha has been a chronicler and teller of Asian American stories for decades (as a former editor-in-chief of the KoreAm Journal and staff writer for the Japanese American newspaper Rafu Shimpo), while Yi, a former neuroscience student, found his true calling as a filmmaker, editor (including the Emmy-nominated Farewell Ferris Wheel), and as an LA Press Club Award-winning journalist.

“Both Julie and I are Korean American, our parents are immigrants, and we’re part of the legacy and the scattering of the diaspora that came out of the Korean War,” Yi told me. Together, Yi and Ha spent more than five years collaborating to tell Chol Soo Lee’s complicated, rollercoaster life story.

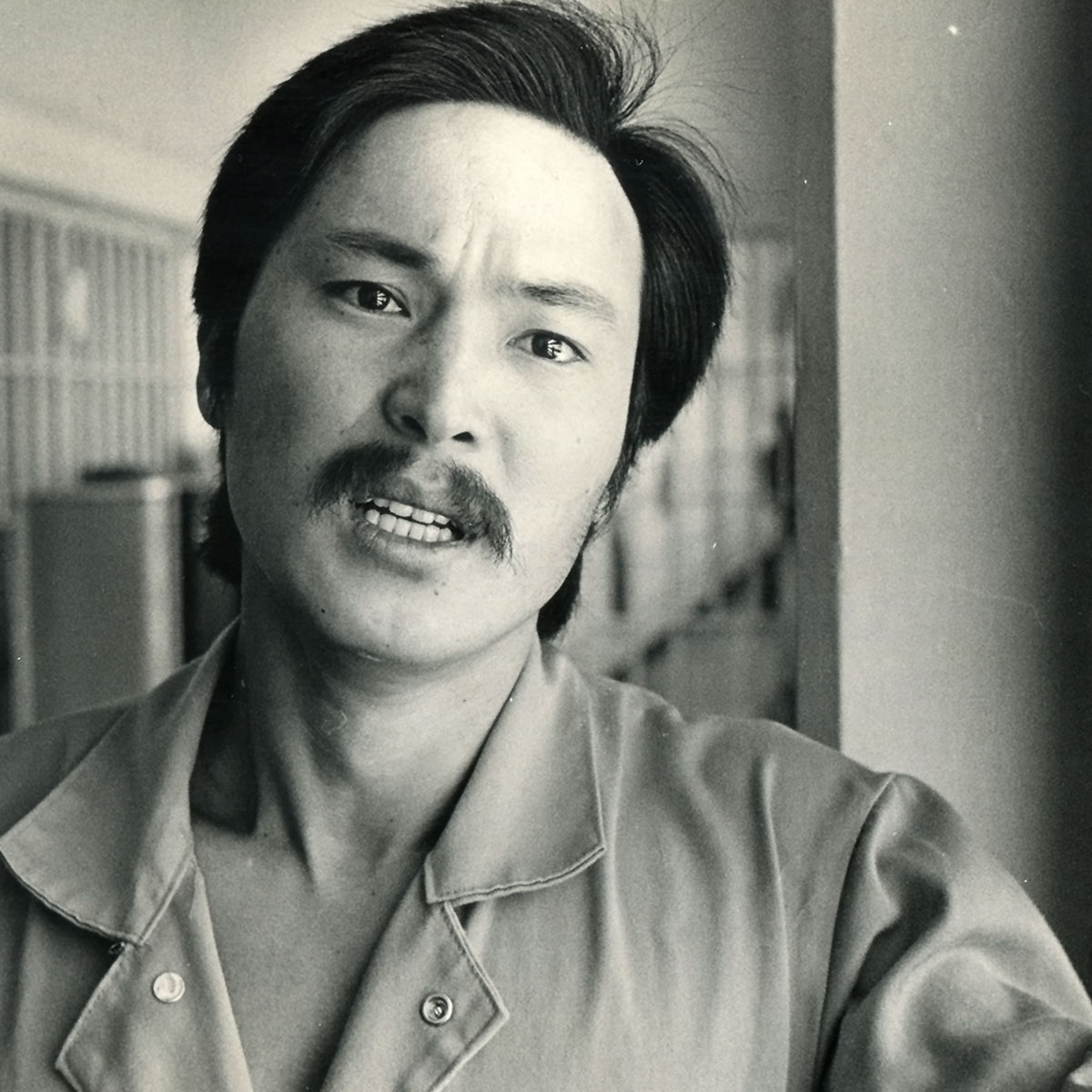

Filmmakers Julie Ha and Eugene Yi

How did you learn about Chol Soo Lee?

Julie Ha: I’ve known about the Chol Soo Lee case since I was 18. My journalism mentor, KW Lee, who is in the film, is the investigative reporter whose story sparked the movement to free Chol Soo Lee. I remember first learning about the case and thinking it was amazing that one journalist’s work could free an innocent man from prison. But that was really not the whole story, I would later learn. The truth was much more complicated and messier.

Eugene Yi: I saw Chol Soo Lee giving a speech in 2013. He was invited to give these speeches towards the end of his life in universities, events that would serve as reunions for the activists. It was a strange and charged environment that I didn’t quite know what to make of. I went in thinking it was going to be a celebration of the social justice movement from the ’70s and instead, because of how his life played out after his release, there was a lot of complicated feelings among the audience.

Why was it important to bring back this story to the public imagination?

Eugene: Many people familiar with Asian American history know the Vincent Chin case and the movement it inspired. The Chol Soo Lee case precedes that movement and in a lot of ways, it’s a link between several of the social justice movements of the 1970s that started to forge the idea of a pan-Asian American identity and movement. This case was one of the pillars of Asian American history.

That made it feel like we should bring it back and bring attention to it, because it doesn’t come up when we talk of Asian American activism. I always imagine someone’s going to be like, “Oh, but have you heard about this Chol Soo Lee case? They got this guy off of death row, it’s crazy.” But it never comes up.

Julie: This story is too important for it not to be known, for it to be buried in history. It just has such complicated, messy themes that Asian American communities don’t always want to talk about. I wondered why the Vincent Chin case gets taught in Asian American Studies as the first pan-Asian American social justice movement. The Free Chol Soo Lee movement was successful, but didn’t have the fairy tale ending everyone had hoped for. I thought that needed to be explored.

Eugene: There is also a subtlety it gives to the conversation about Asian American identity today. I personally find it affirming, as someone who now, as an Asian American, can look back and see that there’s this history and there’s a line we can draw from it. Growing up, there were never any images of radical Asian Americans, let alone an entire movement.

TV news crews surround Chol Soo Lee after he is released from prison on March 28, 1983.

Credit: Grant Din

Both of you knew about this movement that happened in the late 1970s. What made you want to make a film about it beginning in 2015?

Julie: I attended Chol Soo Lee’s funeral in December 2014 and remember feeling a heaviness in the room. It was attended by KW Lee and some of the activists who helped Chol Soo Lee and became his most dedicated friends. The feeling in the room was beyond just mourning and grief. People were saying, “In the end, Chol Soo Lee did more for us than we did for him.”

These people had dedicated six-plus years of their lives, freeing a stranger from prison, and then even after his release, when he was struggling with addiction, they were trying to help him. And yet, they felt so much regret and guilt about what happened to him after his release from prison. I was struck by the depth of responsibility they felt for Chol Soo Lee, and also this overwhelming feeling that there was a lot here to unpack.

When Eugene and I were talking about working together, I mentioned that heavy feeling. We needed to explore it. So we decided to go for it and pursue this story without really thinking too deeply about what it’s like—and how difficult it is—to make an archival film.

Can you talk about, the difficulty in telling Chol Soo Lee’s story?

Julie: Many of the activists who helped Chol Soo Lee, especially the younger ones, told us in interviews, “If we had known how hard it would be to overturn two murder convictions and free an innocent man from death row, maybe we would have given up before we even started.” Sometimes making this film [felt] like that.

Maybe it’s good that I was very naive about the whole filmmaking process. It’s been quite the marathon. But for both of us, it’s also an incredible honor to make this film, to be able to tell this story.

In a way, I feel like it’s provided some kind of catharsis and closure for the many activists and the people who came to Chol Soo Lee’s aid. His life was so hard for so long, even after his release from prison. It’s been the source of a deep ache for many of them and in a way, the process of making this film, and having them open up and talk to us about the highs and lows of the movement, has had some element of healing and release.

This is, of course, an Asian American story, a story of Asian American activism. But would you say it’s also the story of larger America?

Eugene: The core of the story is the relationship between not just race and the carceral state, but between race, poverty, and anything that otherizes and oppresses a community within the State. When you’re talking about prisons, you’re talking about race. We think it’s really important for Asian Americans to know that this is a part of our story and a part of our history. Which means it’s part of our present as well.

Certain Asian Americans feel like they have achieved a proximity to whiteness that shields them from concerns like policing. And it can create fissures or wedges between us and other communities for whom the issue is more front-and-center.

It’s so easy to pit one people against another, and I feel like you see that with the recent attention to violence against Asian Americans, too. There are corners of the internet where people are angry about the fact that some of the perpetrators of this violence are African Americans. It quickly turns into an ugly conversation.

If our film can help provide a more expansive sense of the problems we all face, and the larger forces that can oppress us all, I think that would be my ultimate dream.

TV news crews surround Chol Soo Lee after he is released from prison on March 28, 1983. Credit: Grant Din.

Julie: I think our film has the potential to change the way people view Asian Americans but also how we Asian Americans view ourselves.

We have images in our film where we see Korean immigrant grandmothers holding protest signs outside the courthouses. That’s pretty incredible. Asian Americans back in the late ’70s, early ’80s, didn’t have much political power. For them to assert themselves, and say, “We’re going to get this man out of prison, we’re going to overturn two murder convictions,” that’s an unbelievable story but it’s all true.

How important is it to have Asian Americans tell this story of Asian American radicality?

Julie: There is a 1989 film True Believer, starring James Woods and Robert Downey Jr. that is loosely based on the Chol Soo Lee story. But it’s all told from a white savior perspective. In order to tell the truth of this story, you have to see Asian Americans three-dimensionally, in all our human textures. Eugene and I, as Asian American storytellers ourselves, have that lens and that track record.

Eugene: The film also speaks to the very specific erasure of the story. It’s not just the outside gaze but we also have to be aware of the way the community sees itself and the stories it decides to tell and retell. This story didn’t get told enough. Is it because of his difficulties later in life? Is it because it’s not a story of a tidy hero? I mean, they still got a guy off death row! It sounds impressive, but it wasn’t a story that was chosen to be historicized and memorialized. One has to be self-reflexive.

So much of this film project sounds like an archaeological enterprise. What were your experiences with the challenges of digging through archives?

Eugene: With any image, any archive, there’s always an eye, always a gaze that is present. You have no idea how much footage we’ve seen of Chinatown, from the 1950s, ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, even into the ’90s, that have this “oriental” music and images that build up stereotypes, exoticize the neighborhood.

The ever-presence of that white gaze made it very difficult to work with that archive. There is always a Tai Chi person, a smoked duck in a window. We wanted to de-orientalize Chinatown, and turn it into a community. Of course, the prison archive is its own challenge.

Julie: It’s also not like the archival houses identified this material as “Oh, wow, this is one of the first successful pan-Asian American social justice movements, the Free Chol Soo Lee movement. We’d better preserve these tapes.”

If not for the personal archives of individuals, we would not have a film.

Eugene: It is gratifying we look at an era when technology was starting to become more accessible. Asian Americans were starting to create their own archives through family photos and home videos. That helped us fill some of the gaps in our story. There were people covering and recording their own story, not waiting on formalized archives to take note of their lives.

Julie: People [dug] in their garages for us, looking for things. It’s weird because then as filmmakers, we feel like archivists, too. We have all these materials we want to safeguard.

Eugene: The burden of having to represent this history is bigger than this film. These images and videos belong in the national archives. It’s this country’s history. Not just the Chol See Lee case but any kind of activism comes with that sort of responsibility and a requirement for tenacity. It’s incredible that people are able to do that work. The Chol Soo Lee case seems to embody just how hard that road can be.

How has the story changed in the five-plus years of working on the film?

Eugene: There is our own growth, where we as filmmakers understood what it is like to explain, versus to evoke. The constant narrowing of our focus has allowed the film to center on Chol Soo Lee. Of course, though, there was always a sense the film will be connected to themes of imperialism and colonialism, and the tragedies they left in their wake, the degree to which that shaped our story has changed. We had more time to dig into the archaeological aspect you’re talking about. We had a deeper understanding of Chol Soo Lee’s psychology and were able to absorb that in a way that can be expressed in the film.

Asian American and Pacific Islander students rally at one of many courthouse protests to fight for Chol Soo Lee’s freedom. Credit: Courtesy of Ken Yamada/Unity Archive Project.

What is the legacy of Chol Soo Lee, and how can this film continue it?

Julie: One activist told us that she felt like our film was a continuation of the movement, in terms of perpetuating a meaningful legacy for Chol Soo Lee. After I wrote my magazine story about Chol Soo Lee’s death, someone in Virginia wrote on Facebook that she had heard about the case when she was an undergrad. It inspired her to become a criminal defense attorney. There is incredible potential in this story inspiring a new generation to work toward creating a more just society.

Eugene: It means a lot to be adding to the growing body of documentaries on Asian American history, but we don’t want to be the last word on the case. The hope was to make a realistic activist movie because it’s so easy to romanticize activism in a documentary. There are incredibly inspiring aspects to our film but it’s a fuller story than that.

So many of the activists in our film were college-age when they got involved. We hope it gives an insight into that long journey of Asian American activism that lets you do so much good. We want young Asian Americans to know they are capable of change even when they can’t control the outcome.

[This piece originally appeared in expanded form on the ITVS website.]

Bedatri Choudhury works with documentaries and is a cultural journalist. She lives in New York City.