Telling the Big Story: Science Writer Elizabeth Kolbert

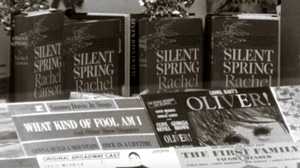

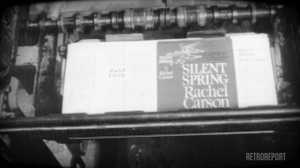

In 1962, The New Yorker magazine published the first of a series of articles by science writer Rachel Carson about the dangerous side effects of pesticides. Those articles formed the basis for Carson’s ground-breaking book, Silent Spring, released later that year. Today, the magazine continues to publish science journalism by writers like Elizabeth Kolbert, whose reporting on climate change first appeared in The New Yorker in 2005. Kolbert is also the author of several books on the topic, including The Sixth Extinction, which won a Pulitzer Prize in general non-fiction. American Experience spoke to Kolbert about the difficult work of a science journalist and why she keeps doing it.

When did you start writing about climate change and what attracts you to it?

I went to Greenland for the first time about fifteen years ago and that sort of set me on this journey. The Greenland ice sheet is two miles thick at its center. When you’re standing on two miles of ice, your view of the world changes — or at least mine did. You realize that the world as we know it is a pretty contingent place. It can change very dramatically and very quickly. It has done so in the past.

I guess what keeps me writing about climate change is the sheer magnitude of the issue, and the importance of it. Why do people get into journalism? Well, they get into journalism basically to tell the big story, and there just isn’t a bigger story right now.

Looking out your window today, the weather you see doesn’t really tell you what’s going on. The earth is big and complicated — and there’s a big time lag in the system. People need to understand that. You know, many people, many scientists, many journalists keep trying to impress that upon the public. It obviously isn’t working very well, but we keep trying.

Who is this “public” that you’re writing for?

I’m trying to write for just about any interested person. Maybe that sounds naïve or clichéd, but it’s really true. I try to write not only for the roughly one million people who subscribe to The New Yorker, but also for those who might find it at the gym or the doctor’s office, or just about anyone who might pick it up — I’m trying to reach all of those people. The key is telling stories that people find compelling. You want to catch your readers off guard, in a way — to get them to read on even if they don’t intend to, if they don’t think they’re interested.

And when someone reads one of your articles, what do you hope it will accomplish?

I think what all nonfiction writers are aiming for is to make people think about things differently — to tell you a story from somewhere that, if you’re vaguely familiar with it, challenges what you think you know about it, or, if it’s a story you’ve never heard before, introduces you to a whole new place or a whole new idea. I’m basically trying to tilt your worldview a little bit.

You write about things happening now that could have devastating long-term effects. Do you feel a special sense of urgency when you write about those topics?

Yes and no. I do feel a sense of urgency, but I also don’t nurse any illusions that what I write might factor into any decisions. If that’s why you’re writing at this point about an issue like climate change, you’re going to be profoundly disappointed.

Climate scientists who’ve admitted to feeling disturbed by their findings have come in for heavy criticism, and there’s a similar stigma against showing emotion in journalism. Is there a place for emotion in your reporting?

I hope that my pieces convey that there’s something to be very, very concerned about here and now. There’s the old saw in journalism, or in writing, in general: “show, don’t tell.” So I generally don’t say, “well, you should really be damn concerned about this.” But I hope it comes through. That goes with writing a certain kind of reported piece as opposed to my opinion. Occasionally, I do write opinion pieces, but generally I’m offering people a piece of reporting, and so how I feel about it is not the subject matter — and I don’t want that to become the subject matter.

Sometimes, the subtlety that comes with that remove is even more effective. I remember reading a piece you wrote about flooding in Miami, and I felt like I could hear you saying “Wow, I can’t believe it’s this bad” — even though you never actually say that in the article.

I’m glad that that was your response to the Miami piece. One of the sort of “house rules,” I suppose, of writing for The New Yorker is that you go someplace, but you’re not a privileged observer. You’re seeing what anybody could see who was in the same situation — that’s sort of the ethos. There’s something to having an outsider come in. People in Miami say, “Oh we’ve seen it so many times, we don’t even really think about it.” But then you come and you bring a slightly different perspective to it, and it starts to look pretty weird.

You’re also dealing with phenomena that are happening over the course of millennia, which can be difficult for people to appreciate. How do you make those events feel relevant to someone’s daily life?

I think it’s a good question, and I don’t have a trick there. I think that really anything that’s more than a century old is in some fuzzy past. So there’s no really wild difference between something that happened 66 million years ago and something that happened 66 hundred years ago. They’re both in some pretty distant past for people. I do often try to ask people to take a long view, which means getting your head in a somewhat different place, and that gets back to what we were talking about, about seeing the world from a somewhat different perspective. It’s not just what happened last week that matters — it’s also what happened a million years ago, fifty million years ago, 500 million years ago. All these things are why we’re here right now, in this situation. Everything, in some ways, had to happen a certain way for this moment to exist.

Why do you think Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring had as much impact as it did? Do you feel like a book of environmental journalism could have as big of an impact today?

Well, some people have suggested that it was because people were just beginning to think of the effects of the fallout from nuclear testing, and Silent Spring really resonated with that. I think that’s quite possible. There were all of these sort of unseen, insidious poisons — we were poisoning ourselves both with atomic fallout and with pesticides. This was sort of a new idea at the time and it really raised alarms with people.

Now, it’s almost like environmental bad news is at its peak, and unless you tell people we’re all going to drop dead tomorrow, they’re all going to discount it as another, “Oh we’ve heard that before.”

I’ll add that even pesticide use has gone way up since Silent Spring. So it’s not like we’ve solved any of these problems, really. Have we even learned the lessons from Silent Spring? Do we ever learn? It’s a very interesting question, to which I do not have a very clear answer.

Since pre-colonial times, Americans' relationship to the natural world has shaped politics, policy, commerce, entertainment and culture. In this collection, delve into our complicated history with the environment through American Experience films exploring wide-ranging topics, from our struggles to exert dominion over nature to our attempts to understand and protect it.