1967 | San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Some Flowers in Your Hair) by Scott McKenzie

From the Collection: Songs of the SummerHow a commercial became an anthem.

By Keven McAlester

What’s the worst song that you love?1 For me, among a large and ever-growing lot of candidates, one clearly tops the list: “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Some Flowers in Your Hair),” a 1967 top-ten summer song by Scott McKenzie.

Look, I’m not proud of this.

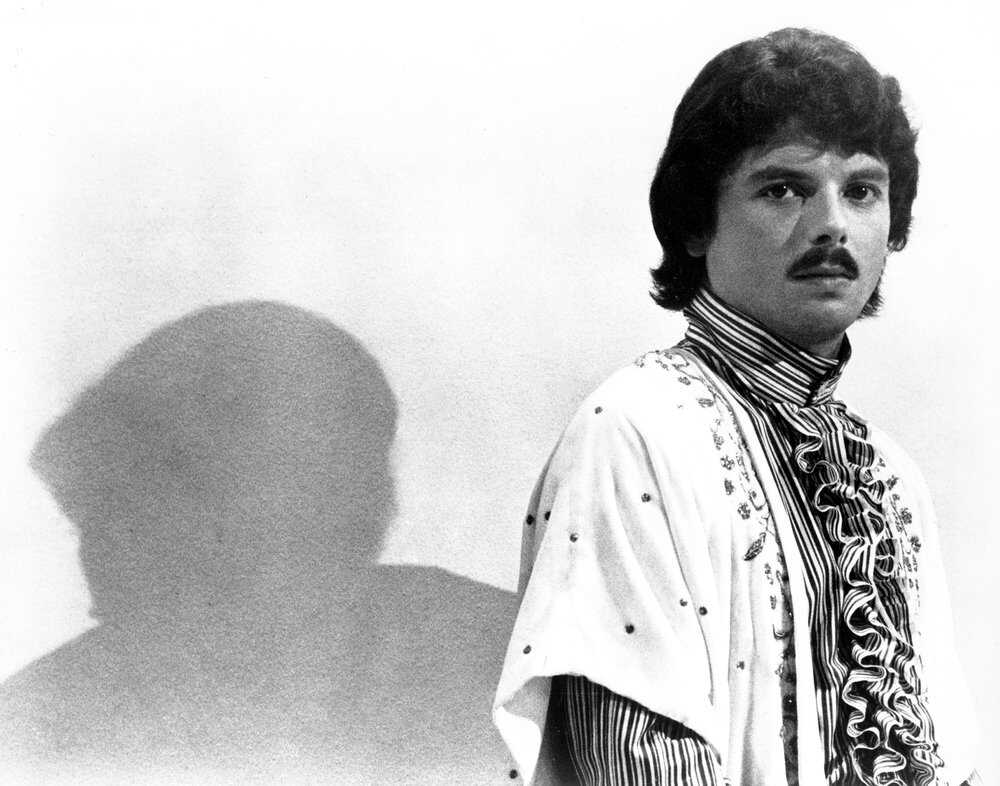

McKenzie, who died in 2012, was a journeyman musician2 whose other claim to fame is co-writing the Beach Boys’ “Kokomo,” itself frequently named among the worst songs ever recorded, and which I do not love at all. McKenzie had a great voice, and at first blush, “San Francisco” could be judged, at worst, merely insubstantial — a straightforward folk-rock song with lyrics that have aged about as well as any other hippie cliché. (“If you’re going to San Francisco, you’re gonna meet some gentle people there,” goes one of the lines, and not since the reign of the Sydney Ducks has a trip to The Bay sounded so unappealing.) If the song merely lacked self-awareness and was prone to aging poorly, it would hardly qualify for any list of worsts, and indeed might even be charming. But the thing about “San Francisco” is, the more you learn about it, the worse it gets.

Turns out the song wasn’t written by McKenzie, but by his friend John Phillips of the Mamas and the Papas — already a crippling fact, if you’re not willing to separate an artist’s personal behavior from judgments about his or her art (after his death, Phillips’ daughter accused him of sexual assault). By his own admission, Phillips wrote the song in 20 minutes, and he didn’t write it because he lived in San Francisco observing or participating in the movement he portrays — during that time, he was mostly hanging out in his Bel Air mansion, buying antiques and snorting cocaine — nor as some writerly exercise of identifying with or trying to understand his subject. No. Instead, it was written and released as a commercial.

Sometime in the spring of 1967, Phillips and producer/music-business-icon Lou Adler took over planning of the Monterey Pop Festival, a now-storied three-day event inspired by the Monterey Jazz Festival. Pretty quickly, given the two men’s cachet, the festival turned into a big deal. But there was a problem: the landowners and political class of Monterey were terrified of being overrun by tens of thousands of hippies. This led Phillips to conceive the idea of writing a song to promote the festival, in which he would implore attendees to not run wild in the streets. Twenty minutes later, “San Francisco” was written. Far from an anthemic celebration, it was part ad and part admonition. It’d be like if N.W.A.’s “Fuck Tha Police” turned out to have been a jingle for a law-enforcement dating service.

No matter; the song became a massive hit when it was released in May 1967, and ended up becoming a sort of unofficial hippie anthem anyway. According to the small handful of articles and books I just found by googling the song, all of the actual San Francisco underground musicians of the day (Janis Joplin, the Grateful Dead, etc.) absolutely hated it. This isn’t hard to imagine. The death of the American countercultural ideal of 1960s has been tied to various events — the SF hippie funeral of October 1967, the assassinations of 1968, the murder at Altamont, Charles Manson — and while those last three quite obviously have the weight and depth of historical tragedy, it’d be hard to find a more poetic starting point than the moment at which a PSA on behalf of the propertied class in Monterey, California became the movement’s unofficial anthem.

So but wait. How I could write all of that and then claim to even like the song, much less love it? My admittedly ill-conceived answer is: I have no idea. Or perhaps it’s just that none of the above actually matters.3 I could come up with some concrete explanations — the great melody, the surprising key changes, McKenzie’s voice, the fact that I can ignore the lyrics, the tune’s overall haunting wistfulness that gives it an air of regret, as if sung by someone in the distant future looking back at the failed idealism of youth — but none of that will mean anything to you before hearing the song, and probably won’t mean anything after. That’s the great thing about music; the images and emotions a particular song evokes, the meaning one attaches to it, are entirely internal, and different from person to person. You can share general tastes with someone, but why one song hits you and another doesn’t isn’t subject to the niceties of fact or reason. So what do I know? Nothing, it turns out.

Put another way: I once read an interview with a Vietnam veteran who said that, to American soldiers stationed there at the time, the song was a “tearjerker,” because San Francisco was a common destination for soldiers en route home.4 In short: in the midst of a grave situation, it gave him hope. And by my insignificant personal standards or any more substantial ones, that qualifies “San Francisco” not as one of the worst songs ever written, but one of the very best.

Listen to the complete top ten from the summer of 1967 on Spotify.

1 Note that “worst” here does not mean “most amateurish.” The Shaggs’ Philosophy of the World is often cited as “the worst record ever made,” but its greatest sins are poor playing and utter guilelessness—which, it turns out, are also its greatest strengths, making it something like essential listening.

2 As if fated by God or Terry Southern, one of his first bands was actually called “The Journeymen.”

3 By which I mean: none of the above backstory actually matters in determining whether you like the song upon first hearing it; clearly recent allegations against Phillips capital-M matter quite a lot.

4 From the book Voices from Vietnam.

Keven McAlester is an Academy Award- and Emmy-nominated filmmaker based in Los Angeles. He has directed two documentary features (You’re Gonna Miss Me and The Dungeon Masters), produced and written three others, and directed over 30 music videos, short films, and PSAs. His work has premiered at the Sundance, Toronto, and South by Southwest film festivals; debuted online in such publications as The New Yorker, Vice, and Impose; and been commissioned by such institutions as PBS, HBO, and the Academy of the Arts, Berlin.

Roll down the windows, turn up the volume and prepare to sing along as American Experience celebrates the music of the season with Songs of the Summer.

In 1958, Billboard launched its Hot 100, chronicling the songs that were flying off record store shelves, playing non-stop on juke boxes, and blaring through radio speakers. Almost sixty years on, how we listen to music and how we track a song’s success may have changed, but music remains a powerful force in our culture. Every Friday from June 2 through August 25, we’ll reveal one iconic song that hit the charts, accompanied by commentary from some of our favorite music writers. Explore our historical mixtape, and check back each Friday for our next track.

Published June 16, 2017.