#HustleAndFly: Amelia Earhart on Instagram

What would Amelia Earhart’s Instagram account have looked like? American Experience decided to find out.

By Cori Brosnahan

In June of 1928, a 30-year-old social worker named Amelia Earhart became the first woman to cross the Atlantic by air on a plane called the “Friendship.” Though Earhart was a licensed pilot with some 500 hours of solo flying under her belt, she had not actually taken the controls during the 20 hour and 40 minute flight — a fact she reiterated again and again to anyone who would listen, crediting pilot Wilmer "Bill" Stultz and mechanic Louis “Slim” Gordon with the achievement. But her attempts to deflect attention were to no avail: all anyone cared about was the “girl flyer,” who looked so much like aviation-god Charles Lindbergh that she was soon known as “Lady Lindy.”

Earhart was an overnight sensation. In her biography of the aviator, Doris Rich described the hullabaloo that ensued. In Burry Port, Wales, where the Friendship landed, policemen formed a human shield around her, lest she be mobbed by the enthusiastic Burry Portians, almost all of whom turned out to see her. Later, in London, she hobnobbed with Astors, danced with a prince, and made an appearance at Wimbledon. Back stateside, thousands gathered to welcome her home with a tickertape parade of epic 1920s proportions. At a charity auction, a small flag Earhart had carried aboard the Friendship inspired a bidding war between Yankees slugger Babe Ruth and “Showboat” star Charles Winninger. (Winninger, the auctioneer, won.)

Earhart had skyrocketed to celebrity in an age where there were not only few women on the public stage, but fewer people period. And the stage itself was smaller — a far cry from the omnipresent feeds detailing celebrity breakfasts in real time today.

“She had so much less competition for her celebrity back then,” says historian Susan Ware, author of Still Missing: Amelia Earhart and the Search for Modern Feminism. “The whole popular culture wasn’t as crowded. In Hollywood, they had a huge publicity machine, but all that did is crank out these little puff pieces. It was not real. Nobody expected it to be. But Amelia was.”

Granted, Earhart had become the first woman to fly across the Atlantic because the Friendship flight’s promoters deemed her “the right sort of girl” for the job. Nevertheless, her authenticity was never in doubt. No, she wasn’t the best female pilot flying, but she always flew, setting some dozen aviation records, and becoming the first woman to cross the Atlantic solo, in 1932.

But unlike the starlets in Southern California, Earhart had no institutional machinery behind her — or even a career path to follow. Besides Lindbergh, few pilots were able to make a profession out of their very expensive sport. And while the Friendship flight had brought a flush of opportunity her way, Earhart and her publicist-turned-husband, George Palmer Putman, realized that if she wanted to keep flying, she had to keep herself in the public eye.

And so she engaged in a distinctly modern hustle — self-promotion through (almost) any means necessary.

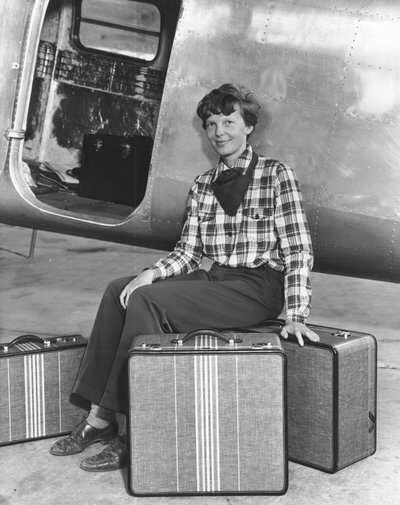

She turned around books about her exploits at lightning speed. (Her first, 20 Hrs. 40 Min., hit bookstores less than three months after the Friendship landed at Burry Port.) She stormed the country on lecture circuits, at one point delivering 23 talks in nearly as many days — all while driving herself from town to town. She wrote articles for various newspapers and magazines and became the “aviation editor” for Cosmopolitan. She became a prolific endorser of products ranging from Lucky Strike cigarettes to Kodak film to Beechnut gum and Horlick’s Malted Milk cubes — though, according to Barbara Schultz, author of Endorsed by Earhart, she turned down the truly random (rabbit meat) and the potentially exploitative (children’s hats). She partnered with the Orenstein Trunk Corporation of Newark, New Jersey to create her own luggage line, and designed a line of fashionable “active clothes” for women. On her flights, she carried sacks of envelopes that admirers had purchased to have postmarked and sent from Earhart’s far-flung destinations.

A deft practitioner of the publicity stunt? A content marketeer? An athleisure pioneer? In the 1930s, Amelia Earhart had all the marks of the modern celebrity. But unlike modern celebrities, Earhart didn’t have the advantage — or the onus — of her many fans at her fingertips at any given moment. In other words, she had no Twitter, no Facebook, no Instagram.

But what would it have looked like if she had? Would she even have used it?

“Of course,” said Susan Ware. “There’s so much evidence that she consciously worked to promote herself in the ‘30s that I think we can assume she would be doing whatever the equivalent is now. And not necessarily begrudging it. It’s a lot of work, but she knew that was what it took.”

Earhart, who worked at a photography studio in her twenties seems to have dabbled in the art. In her second book, The Fun of It, she wrote: “I tried photographing ordinary objects to get unusual effects, and made a number of studies of such things as the lowly garbage can, for instance, sitting contentedly by its cellar steps, or the garbage can alone on the curb left battered by a cruel collector, or the garbage can, well — I can’t name all the moods of which a garbage can is capable.”

That glimmer of interest, along with her absurdly photogenic visage (a Kardashian could only hope to look that good after piloting a 20-hour flight), and a penchant for travel to exotic locales would seemingly have made Earhart a natural Instagrammer.

So what, besides garbage cans, would she have shared? Ware said that while Earhart was very private in her personal life, “as soon as she got in that plane, she would have wanted to tell you what her airspeed was and what it looked like out the window. She would have been Instagramming while she was flying — things like ‘amazing clouds’ or ‘this reminds me of something.’”

But she wouldn’t have stopped there. Alongside a well-filtered photo journal of her day, Earhart likely would have used social media to elevate a critical message or two.

“She didn’t just fly for herself, she flew for women,” says Ware. “She deliberately pushed this message to encourage women to follow their dreams and do what they wanted.”

And she flew for aviation itself. At the time, the American commercial airline industry was in its infancy and flying was still widely considered dangerous. Earhart embraced her role as spokesperson, seeking to convince the public that air travel could be safe and enjoyable. Surely, flying through the clouds would have seemed more enticing with a Perpetua or Skyline filter.

Ware also advised that Earhart would have been loathe to turn down a fan selfie. “She was always very gracious about autographs and autographs are the equivalent of selfies. I can just see her doing that — she loved interacting with her fans. Maybe that’s another thing that made her so modern. She loved that human contact.”

As for solo selfies, Ware can imagine George Putnam nudging his wife/client to, “show them what you’re having for breakfast,” but doubts that the aviator herself would have been interested. Earhart, after all, was real; she would have been too busy with the control stick to worry about the selfie stick.

So what does the American Experience staff imagine Amelia Earhart’s Instagram account might look like? Follow @RealAmeliaEarhart to find out.

Sources & Methodology

Photos for @RealAmelia Earhart come courtesy of the following sources:

Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University; Purdue University, Archives and Special Collections; Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum; Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery.

Quoted caption text comes from the following books:

Amelia Earhart, 20 Hrs. 40 Min. (G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1928).

Amelia Earhart, The Fun of It (Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1933).

Amelia Earhart, George Palmer Putnam, Last Flight (Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1937).

Additional sources include:

Barbara Schultz, Endorsed by Earhart (Little Buttes Publishing, 2014).

Doris Rich, Amelia Earhart (Smithsonian Institution, 1989).

Susan Ware, Still Missing: Amelia Earhart and the Search for Modern Feminism (W.W. Norton & Company, 1993).

Hashtags are of our own creation.

Published July 2, 2017.