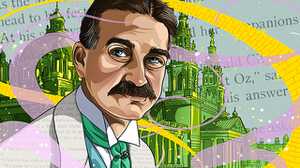

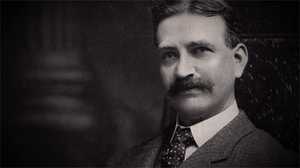

Why Is the Wizard of Oz So Wonderful?

Considering L. Frank Baum’s classic and the generations of adaptations it inspired.

What is L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz—the original story, published in 1900—about, anyway? If you asked people this question in the first half-century of the book’s existence, they might have shrugged: It’s a children’s story; it’s just for fun. Starting in the middle of the 20th century, scholars made their cases: It’s a populist take on the plight of Western farmers in the late 19th century; no, it’s a pro-capitalist parable of industrialization and consumerism. And latter-day artistic adaptations of the Oz story, of which there are many, have gone in such different directions—from the 1939 MGM musical’s fun and joy to Wicked’s darkness and suffering—that it can be hard to make a coherent argument for the effect of Baum’s story on American art.

Perhaps the potency of the Oz story lies not in a specific interpretation of its meaning, but in its ability to serve as a blank canvas for so many kinds of American fantasies. Oz has been a way to explore themes of friendship between strangers; of journey and home; of human flourishing against the odds. “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz contains many of the ingredients of the magic potion” that Oz audiences have come to know and love, writes Salman Rushdie in his influential essay on the MGM adaptation that hit screens in 1939. “But The Wizard of Oz is that great rarity, a film that improves on the good book from which it came.” Rushdie refers only to the MGM movie, which he loved as a child, but this idea applies to other interpretations of the book, many of which are arguably artistically richer and more internally consistent than Baum’s original Oz series. Baum wrote an optimistic American fable about one group of friends’ path toward happiness; latter-day artists have seen its potential, and flown.

In celebrating the MGM movie, Rushdie puts his finger on a few qualities that define many post-Baum Oz-inspired stories. He loves the MGM movie for being humanist—a quality many Oz adaptations share. The film is “breezily godless,” he writes; it creates a world in which “nothing is deemed more important than the loves, cares and needs of human beings (and, of course, tin beings, straw beings, lions and dogs).” But perhaps Rushdie’s most perceptive observation is his point about the MGM The Wizard of Oz’s unusual focus on a triangle of powerful female characters—Dorothy, Glinda and the Wicked Witch of the West. The Wizard’s influence, which seems so huge at the beginning of the story, eventually melts away. In an oft-quoted line, Rushdie observes that in the film, “The power of men is illusory…The power of women is real.”

The MGM film is also a feast for the eyes. Historian William Leach writes that the original book The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was a consumer fairy tale of the prosperity kingdom, “where abundance is permanent and starvation unthinkable.” Leach points out that in the 1910s, the Oz story fueled a “lively industry” of toys, games and coloring books and became a centerpiece of advertising campaigns. He argues that Baum’s vision of the Emerald City as a site of consumer pleasure—the houses and streets that seem, with green glasses applied, to be covered with emeralds; the green candy, popcorn, and clothing available for sale; the city’s children buying green lemonade with green pennies—translated excellently into real-world commerce. This reminder of Oz’s significance in its day explains a lot about the dreamy, delicious visual quality of the 1939 adaptation. Leach points out that the original first edition of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, illustrated by William Denslow, was also incredibly colorful, with every page reflecting the hues that Baum assigned to the various parts of Oz: blue for the Munchkins, red for the poppy fields, brown for the Dainty China Country and so on. The beautiful movie made in 1939 was just what Baum wanted from Oz: a story of pleasure, curiosity and fun.

If the 1939 film was a celebration of an American ideal of abundance, the story’s most famous 1970s reinterpretation cast a critical eye on our supposed prosperity. The Wiz, a show that debuted on Broadway in 1974, was the brainchild of a DJ, Ken Harper, who imagined a Motown version of The Wizard of Oz. The show was a success, earning seven Tony Awards, and was made into a 1978 movie directed by Sidney Lumet, with a soundtrack produced by Quincy Jones and an all-Black cast chock-full of stars: Diana Ross as Dorothy, Nipsey Russell as the Tin Man, Richard Pryor as the Wizard, Lena Horne as Glinda and 19-year-old Michael Jackson as the Scarecrow, in what ended up being his only feature film role.

In Lumet’s filmed version of The Wiz, Dorothy—played by the much-older-than-archetypal Ross as an anxious, jumpy teacher in her early twenties—is a homebody who has “never been below 125th Street.” She is uncomfortable in social settings, even at family get-togethers; at the beginning of the movie, her kindly Aunt Em is trying to get her to move into her own apartment with her dog Toto, so that she can gain some independence. A cyclone deposits Dorothy not in a mystical and otherworldly Oz, but in an enchanted Manhattan, full of sharp contrasts between the glam and glitz of wealth and the trap of poverty. The Wiz makes New York City strange via the appearance of costumed Munchkins, Scarecrows and Lions who sing and dance, but recognizable by its landscapes and landmarks: the subway, Coney Island, the New York Public Library, the World Trade Center. The Wicked Witch of the East, “Evermean,” is the Parks Department Commissioner, who freezes children in place after finding them putting up graffiti; the Witch of the West, “Evillene,” runs a sweatshop.

The Wiz, latter-day critics have recognized, can be described as Afrofuturist—part of a loosely defined genre that mixes science fiction and fantasy with history to reimagine a range of Black futures. The Wiz has an odd emotional rhythm; in the spoken parts of the movie, Dorothy is constantly afraid and anxious, and then a big musical number breaks in to provide an upbeat interlude. This, Lumet said later in defense of the movie (which was a box-office and critical failure), was intentional. “Every scene was a scene of liberation,” Lumet said. “Somebody always starts stuck or immoveable, then makes…progress.” At the end of the movie, when Dorothy and her gang free a group of sweatshop workers from Evillene’s grip, the workers strip off their costumes and, in their underwear, sing and dance a song of jubilee: “A Brand New Day (Everybody Rejoice).” Dorothy joins right in, dancing with joy.

After a live television special aired in December 2015 to celebrate the musical’s 40th anniversary, Vann R. Newkirk II described The Wiz as “a masterpiece of Afrofuturism, science-fiction and fantasy, salvation and humanism.” From Newkirk’s point of view, Dorothy’s complexity in The Wiz—her fear and skittishness—is an entirely appropriate evolution from the Dorothy Gale of the 1939 MGM movie, who he sees as “an altogether unqualified conqueror” who’s part of “a strong tradition of endearing white heroes whose main qualification seems to be their grit.” The relocation of the action to the city, the all-Black cast, Dorothy’s struggles toward happiness—all read to Newkirk as “Afrofuturism at its core: taking the bones of an imaginary world built on exclusion and breathing into them the spirit of Black struggle and identity.”

If The Wiz gave Baum’s work new depth by connecting it to themes of Afrofuturism, Gregory Maguire’s 1995 novel Wicked and its three sequels, framed as prequels to Baum’s books, recreated the fantasy world as an extended meditation on power and politics. Maguire’s Wicked novels are deep and complex fantasy visions, with female protagonists at the center. These women navigate an Oz with many competing factions; the stakes are high and violence constant. As a young reader of Baum’s Oz books, Maguire writes, “I found the insularity and parochialism of Oz’s separate populations puzzling and, maybe, worrying. Racist, even, though I hadn’t a word for it yet…Certainly lacking in intellectual curiosity.” Maguire’s new fictional Oz takes that insularity of Baum’s world and transforms it, creating a land full of politics where overlapping peoples constantly interact, ruled by a Wizard bent on domination. A driving force of the Wicked story is the Wizard’s oppression of Oz’s sentient animals (called “Animals” with a capital A). The protagonist Elphaba—the future “Wicked Witch of the West,” whose name the author formed using L. Frank Baum’s initials—uses terrorism to fight back against the Wizard; her friend Glinda chooses a softer route of resistance.

The books amplify another theme of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz: the Wizard’s use of technology to bewitch his subjects. In later books, Baum explored this idea a bit more; “Tik-Tok,” a mechanical wind-up servant, appears in Baum’s Oz novels starting in Ozma of Oz (1907). Tik-Tok is a proto-robot made of copper with clockwork guts. (He wouldn’t have been called “a robot,” since that term wasn’t in use until 1920.) Baum used Tik-Tok in a musical, “The Tik-Tok Man of Oz,” which he then re-adapted into a book, Tik-Tok of Oz (1914).

Maguire reuses the idea of a mechanical servant in Wicked, in which a device named Grommetik belongs to one of the villains of the story, Madam Morrible. The ethical implications of a person owning such a borderline-sentient “tiktok” servant are profound, especially when (as happens in the book) Madam Morrible may have used Grommetik to commit murder. With the character of Grommetik, Maguire seizes on Baum’s beautiful fictional invention to explore another enduring question in American life: When technology dazzles us, what darkness might that dazzle hide?

The musical adaptation of Wicked, which opened on Broadway in October 2003, features music and lyrics by Stephen Schwartz and a script by Winnie Holzman. The Wicked musical takes Maguire’s complex story, slims it down, and brightens it up, making it mostly about the friendship between Elphaba and Glinda. In the musical, the prickly, intelligent, green-skinned political activist and the vapid blonde socialite become friends as they figure out how to respond to the Wizard’s machinations in Oz. Schwartz said in a 2005 interview that he thought of the Wizard’s persecution of Elphaba, an advocate for the rights of the Animals, as parallel to Nazi Germany's persecution of Jews; in the post-9/11 climate, the scapegoating of an “outsider” had many other more American resonances.

Despite these notes of darkness, the musical has a happy ending for everyone, while the Maguire books most certainly do not. “The tone of the show is at once clever and sweet, earnest and witty, sentimental and perky; its message is humanist and feminist,” writes scholar Stacy Wolf. The Wicked musical was a resounding success, nominated for 10 Tony Awards and winning three; it made its investment back in record time, and the cast album won a Grammy and went platinum. As Wolf writes, teenage girls were a huge fan base for the show. The scholar visited active forums on various Wicked fan sites and found them dominated by girls ages 12 to 20, who talked through the emotions they felt about the friendship between the two women, identified themselves as “an Elphaba” or “a Glinda” and made plans to see the musical in person. The adaptation’s feminist slant clearly resonated.

The fantasy of Oz has served as a frame, letting generations of artists fill in the details. From the 1939 MGM film’s beautiful celebration of four friends’ journey of self-realization, to The Wiz’s 1970s Afrofuturist vision of New York City, to the Wicked books’ dark story of authoritarianism and resistance, and the Wicked musical’s exploration of female friendship, Oz has given American readers, viewers and theatre-goers a wealth of alternate worlds helpful for thinking through their own. Though Baum may not have intended to provoke any of these latter-day meditations on power, friendship and humanity, he created a story that gave them ample room to grow. As Maguire wrote in the 2013 introduction to an anthology about Oz: “Oz is nonsense; Oz is musical; Oz is satire; Oz is fantasy; Oz is brilliant; Oz is vaudeville; Oz is obvious. Oz is secret.” To which one could add: Oz is American, and it shows.

Rebecca Onion is the author of Innocent Experiments: Childhood and the Culture of Popular Science in the United States. She holds a Ph.D in American Studies from the University of Texas at Austin and is a staff writer at Slate.