The Wizard in the White City

L. Frank Baum’s long and winding road to Oz, and the Chicago World’s Fair that inspired his life’s work.

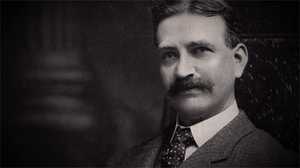

L. Frank Baum needed a new life. In February 1886, his brother and business partner Benjamin died of pneumonia. The two Baum brothers had launched their venture, a petroleum byproduct called Baum’s Ever Ready Castorine, from their father’s successful oil refinery. Frank’s heart had never really been in the family business, though, so when his father died in February 1887, Frank resolved to start over.

It wouldn’t be the first time Baum reinvented himself. The 31-year-old was a master of self-transformation, both by choice and out of necessity. The range of occupations he’d already held were enough to fill several biographies: poultry fancier, actor, singer, playwright, producer, now axle grease salesman. None of these ventures, however, had succeeded in providing both fulfillment and food on the table, and he had a growing family with two young sons to support.

In 1888, after visiting his wife Maud’s brother in the Dakota territory, Baum moved his own family from Syracuse, New York out west. “In your country,” Baum wrote to his brother-in-law, “there is an opportunity to be somebody.” Land agents pitched Aberdeen, a settlement in what would soon officially become South Dakota, as a city on the rise, a blank slate full of possibility and potential. Casting himself as a self-made man, Baum meant to claim his own piece of the country; no matter that his family was homesteading on land that the Sioux tribes had called home for generations.

But the shimmering city on the prairie proved to be a mirage. Weather in Aberdeen was extreme, and the economy followed its vicissitudes. Long, hard winters followed on long, hot summers, and every rung of society, from banking to farming, felt the effects of those conditions. When they arrived in the Dakotas, Baum made a quixotic attempt at opening a business, a shop called Baum’s Bazaar that sold luxury items and whimsical toys and ornaments. Then a harsh drought in 1889 brought financial ruin to many in the area. No one sought whimsy, and Baum’s turn as a shop proprietor came to a close on New Year’s Day, 1890.

He sank the funds he recouped from a buy-out of the Bazaar into a new enterprise, an existing newspaper that he renamed the Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer. Already by the winter of 1891, though, the Pioneer was a lost cause. The paper’s operations had become unsustainable to the point that Baum was funding it personally. In its decline, the Pioneer was going the way of many businesses in Aberdeen. The frontier town’s prospects had turned out to be far fewer than those promised by the sales pitches that had lured Baum out west, three years earlier. The shuttered newspaper marked the next in what had become a string of failures.

Even as the Pioneer’s fortunes waned, Baum saw signposts pointing to a new future. The wire reports reaching his editor’s desk contained a growing number of stories about the imminent arrival of the World’s Fair in Chicago. Also known as the World's Columbian Exposition, in honor of Columbus’s landing 400 years earlier in the so-called “new world,” the fair was to be the largest individual event in American history. An April 1890 act of Congress declared it would be held in Chicago, which had won out over New York, Washington, D.C. and St. Louis, and the already booming city was poised for even more growth as a result.

Baum made plans to raise stakes. He hoped for yet another fresh start and for his family to leave hardship behind on South Dakota’s dusty plains. On a January 1891 visit to the city, already anticipating the end of his run as a newspaper publisher, he secured a gig at the Chicago Evening Post. Maud waited until May of 1891 to join Baum in the city. She arrived with a newborn, making for four young sons in all. Unfortunately, at $20 a week, that job proved too little to secure the Baum household.

While Baum was still on the Evening Post staff, however, the paper ran a tantalizing story about a wizard: Thomas Edison, the “Wizard of Menlo Park,” known for the astounding creations emerging from his research lab, which was originally located in Menlo Park, New Jersey. Edison was among the country’s leading talents tapped to realize the grand ambitions of the Chicago exposition, and the Evening Post reported on a May 1891 press conference in which the inventor hinted at magic acts he was planning for the exhibition. “Greatly interested in the world’s fair is the wizard,” reported the Post. “It has been stated that the invention which Mr. Edison is to exhibit at the fair as his piѐce de résistance is something that will surpass in its surprises anything that ever came from his wonderful workshop.”

Another two years would pass before the World’s Fair formally opened. Still, the city was abuzz with news of its progress. Public interest was so great that even as the fairgrounds were being built, thousands of people per week paid to visit them under construction. Meanwhile, Baum, still struggling to stay afloat, took a sales job at a wholesale crockery firm.

When the great fair finally opened on May 1, 1893, Baum joined the quarter million attendees gawking at the vision within its gates. The White City consisted of 14 brilliantly white neoclassical structures. This Court of Honor, as it was called, was arrayed around the Great Basin, an artificial lake more than eight football fields large, and populated with a collection of birds that Baum, the former poultry breeder, must have appreciated. Yet the alabaster structures were a grand illusion: steel skeletons sheathed in a mixture of jute, glycerin and painted plaster of Paris. When Baum first laid eyes on the White City, it’s possible its outer layers were still wet. At night, the buildings shone just as bright—more lights illuminated the fairgrounds than there were lighting all of Chicago. Seven years later, audiences would read about another glistening city in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz: “[I]f you did not wear spectacles the brightness and the glory of the Emerald City would blind you.”

All of that magic was some way off in May 1893. In the coming year, the United States plunged into the deepest depression in its history. Baum witnessed at a national level what he had already lived through in Aberdeen: businesses and banks closing, widespread unemployment and livelihoods lost. After the fair closed, two fires ripped through the White City and took its optimistic vision of the future up in flames.

Yet Baum already had what he needed, not just for another personal reinvention, but for the invention of a new world. With rare artistic alchemy, he transformed all that he’d borne witness to: the flat midwestern plain, an enigmatic wizard, a dazzling metropolis.

At 44 when The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was published in 1900, Baum finally found his way, and along with it an enchanting fairytale that became a new American classic.

“How can I get there?” Oz’s wandering heroine asks the Witch of the North in her long quest to get back home. “You must walk,” comes the response. “It is a long journey, through a country that is sometimes pleasant and sometimes dark and terrible. However, I will use all the magic arts I know of to keep you from harm.”