An Assassin's Flight From Justice

Filmmaker Barak Goodman has made American Experience programs including The Lobotomist (2008), The Boy in the Bubble (2006), Kinsey (2005) and The Fight (2004). In over a decade of producing documentaries, Goodman has received every major industry award: the Peabody, duPont-Columbia, National Emmy, and an Academy Award nomination.

Here, Goodman describes making The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, including dramatic recreations of the manhunt forJohn Wilkes Booth.

Where did you shoot the recreations?

Most were shot in southern Maryland or Virginia, in the same places that John Wilkes Booth escaped during his 12 day run. For example, when we were shooting the scene where Booth is getting his boot cut off and he is taken upstairs, we were shooting in the same place where that actually happened. Where we shot crossing the Potomac was more or less the spot as where John Wilkes Booth crossed. The barn burning was literally a mile or so from the actual spot where the real barn burned down.

Did you really burn down a barn?

Oh yeah. That was one of the most challenging parts of this production and I really compliment my two associate producers for this. WGBH was concerned about insurance issues so we were not allowed to burn down a building without a very expensive pyrotechnic expert there. Luckily, we found a willing farmer who wanted his barn burned down and we found a willing fire department that would let us film it.

It was quite a scene. We had probably 50 local people gathered there to watch — they sort of made it into a tailgating thing with picnics. It was really a spectacular scene.

How did you figure out what everything should look like?

We had a really good research team and we hired a consultant who knew the story in such detail… we discovered her living in one of the homes that Booth stopped at during his escape. She knows everything about the story — the way the wind was blowing, the exact date of the Derringer pistol Booth would have held, just what he would have worn that night. We felt that we were sinking into the past in a very real way. In fact, one of the horses we used is missing an eye, and Booth’s of course was missing an eye. The same eye, coincidentally. It went down to that level.

Almost all the people who worked on the reenactments were themselves Civil War reenactors. For many of them, it’s a passion. Many showed up on set in costume, walking around in uniforms. We all felt like we were there — despite all the 21st-century filming equipment there was such a spirit of getting at the real thing, and I think it really shows.

How did you learn all the details that were in the film?

That was part of our research. There is an abundance of original materials out there. This is such an important story to so many people that they’ve managed to preserve and unearth every letter, diary, photograph that could possibly be found, and we had all those available to us. We know what Booth was thinking, what Stanton was thinking.

You have to remember that this was an era in which people wrote each other letters, they wrote in their journals constantly. Five different peoples’ journals chronicled what the room looked like where Lincoln was dying. And though some accounts contradicted each other, we know more or less minute by minute what happened during the assassination.

When Kennedy was assassinated it was all captured on film — we don’t have tape itself [for Lincoln], but we have these vivid recollections from the people who were there. It really is a historical record.

Where was Booth’s journal found?

It was on his body when he was killed. It is just chilling to think, here were these words written in those moments while he’s cowering in the pine thicket or on the side of the Potomac while thousands of troops are looking for him. It’s as if Lee Harvey Oswald had stopped right after he shot Kennedy and written down all his feelings.

Even Booth, who was not a great writer, managed to get across his emotional state. You can hear in the words his sense of outrage. He feels like, “how could I be so wrong about how the world would react to this?” It shows how delusional he was about this, seeing the world incorrectly, believing that people were going to see him as a hero.

Did your thinking about Booth evolve during the production?

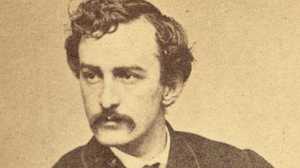

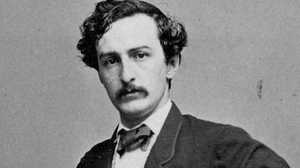

Yes… I had imagined he was a kind of loser, a failed actor, of the same kind as a lot of the presidential assassins have been, nursing grievances against the world. But he wasn’t at all.

To my surprise I found out he was a sort of matinee idol type, surrounded by admirers. That made his motivation all the more perplexing and mysterious. I became fascinated by, why did he do it?

We don’t provide the answer in the film because it is impossible to know. We just try to provide an understanding of the context that might have led someone like Booth to perform this extraordinary act. It was the madness of the times, not just the madness of Booth. There is a great quote in the film, to the effect of, “millions disliked Lincoln, but only one stepped up to him with a pistol.” That’s the real question. Why this man? That’s really the engine of the film.

What kinds of challenges did you encounter?

We shot a lot of our recreations in the middle of nowhere — out in swamps, way far away from electricity, and we needed to control the environment. For one scene we used this gigantic hot air balloon with lights in it to light scenes on the river’s edge. It floats up in the trees and acts kind of like a moon, creating enough light to see the actors but not too much.

Also, any time you work with horses and need them to gallop when you want them to gallop and stop when you want them to stop — that was a challenge.

The casket we used is an exact replica, done by the same casket company that made the original casket. It was very ornate — not like Lincoln’s personality at all. It had metal floral designs on the outside. You can see it in some of the pictures if you look carefully. It does not look like an ordinary casket; it’s almost like they said, “how can we make this look special?” We didn’t have to commission it — they have a set of replica caskets.

One incredibly lucky thing was that the actor who played Booth was the spitting image of Booth. I looked at photograph after photograph and I could not tell them apart. It was like Booth come to life — his thinness, his features, his dark eyes. The actor wanted to be Booth for a few weeks; he wanted to stay in costume the whole time. Even though we never see his full face in the film, it just heightened the sense of it being the real thing.

What was the atmosphere like in the theater?

Unfortunately Ford’s Theatre itself was being completely renovated when we were shooting. That was the one piece of bad luck that we had.

We found an old theater in Richmond, Virginia that we could use to simulate Booth’s career. I think in some ways the hardest reenactments were the stage reenactments. We ended up shooting sword fighting because that was what Booth was known for. It ended up being very stylized.

Fortunately there are wonderful photographs of Ford’s Theatre. In one way I’m glad the real theater wasn’t available for us, because it forced us to use the archival photographs. All we used were simple photos of the president’s box, of the stage, the empty chairs, those chilling interior photographs of the theater as it actually was.

What was it like on the set in the woods?

We shot in Caledon State Park for most of it, and we also used a private farm. We were shooting in April and May, which was perfect for the story but it was definitely iffy weather. We had to blow in huge amounts of fake smoke and fog. Except for one day, it didn’t actually rain on us — the rain was manufactured. It was cold, it was tick infested. Everybody on the shoot had 20-30 ticks to pick off their body.

Did you have any surprises?

We had our usual share of mishaps. There was supposed to be a guide boat that would pull the rowboat down the Potomac but the guide boat broke down, so one of our crew members literally had to drag it down the Potomac for two miles — he was walking on the river bank and the boat was in the water. He was a hero for doing that.

What thoughts do you take away from this film?

I spent a wonderful 18 months immersed in Lincoln’s life. He was both a greater man and a more imperfect man than I had realized. A lot of us think Lincoln was perfect, but he suffered so much. That was the most vivid thing that I learned about him. How personally he took the losses and the deaths in the Civil War, and of course his own son dying too.

It was such a study in courage and character — a person who was put in such extreme circumstances and instead of being filled with hate by it, he grows. I think that’s the greatness of Lincoln. He was able to adapt and change and transform his opinions. He had to change totally, in this cauldron of the Civil War, and if he hadn’t, our whole history would he different. I grew to admire him, but not in the ways I thought I would.