Before Loving

Nineteen years before the landmark case, California legalized interracial marriage

By Erik Mangrum

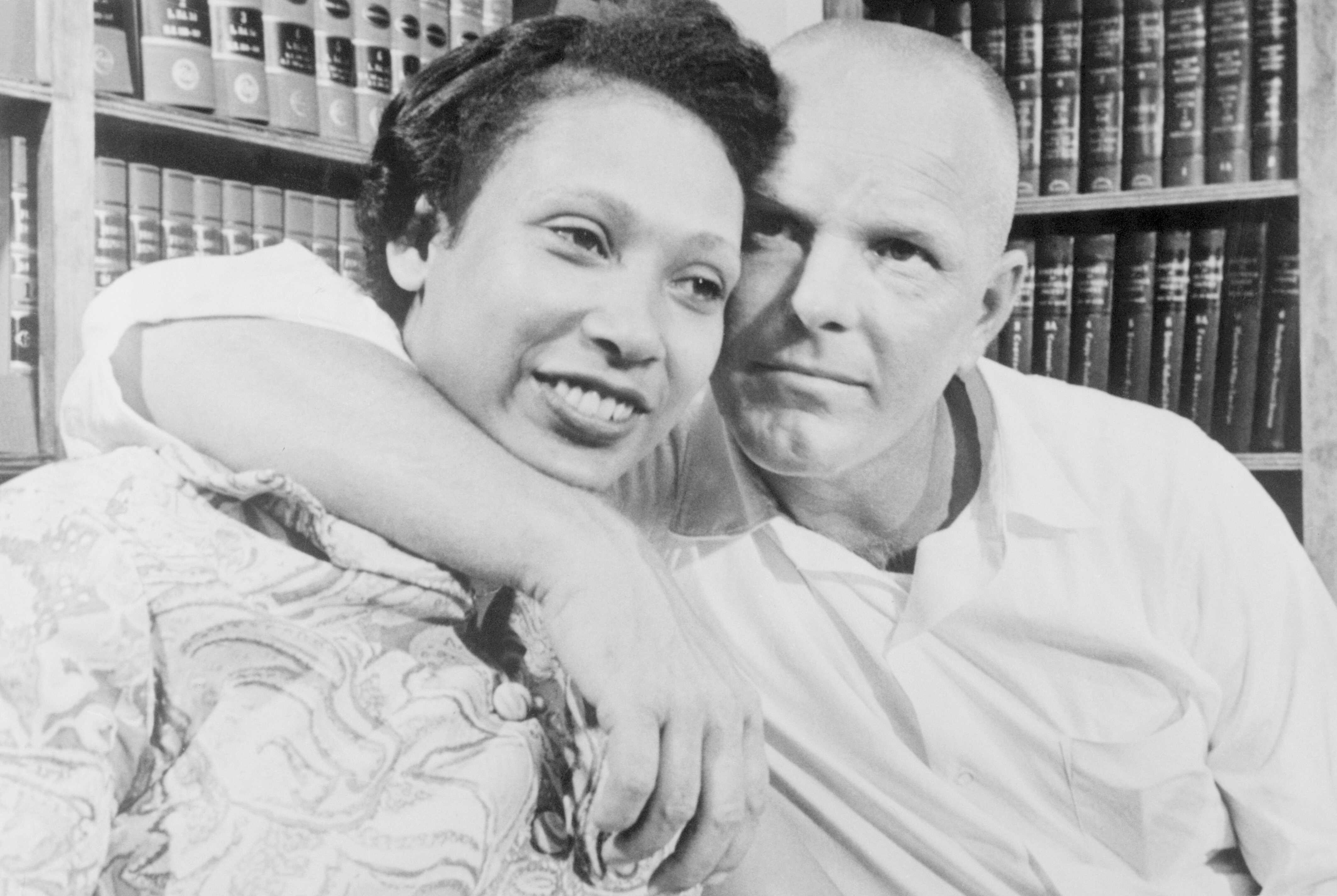

On June 12th, 1967, Love stood tall. Loving v. Virginia is the Supreme Court case that struck down anti-miscegenation laws in Virginia, effectively legalizing interracial marriage throughout the nation. The couple who brought the case, Richard and Mildred Loving, became symbols of marriage equality who are still celebrated today.

But in the footnotes of Loving — a unanimous opinion from the Court, delivered by Chief Justice Warren — there was a reference to another case, argued nineteen years earlier.

In 1948, Sylvester Davis and Andrea Perez of Los Angeles, California, applied for a marriage license. They were denied. The county clerk, W.G. Sharp, refused to issue them a license, citing California Civil code, which states, “All marriages of white persons with Negroes, Mongolians, members of the Malay race, or mulattoes are illegal and void.” On the face of things, some may have questioned the denial, as Sylvester Davis was African American and Andrea Perez was of Mexican descent. But under the California law at that time, Mexicans were classified as white, due to their “Spanish heritage.”

“[Administrative clerks] are really gate keepers,” explains Robin A. Lenhardt, a Professor of Law at Fordham University and author of The Story of Perez v. Sharp: Forgotten Lesson on Race, Law, and Marriage. “I think the clerk in this case, wasn’t necessarily going by color. She understood, for purposes of marriage that go back to the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, that Mexican Americans would be treated as white. Interestingly you see the administrative clerk playing the same role in the early same sex marriage cases.”

Davis and Perez wanted to get married in their church, where they had been longtime members. Lenhardt explains, “They could have gone to another jurisdiction to marry because California, unlike Virginia, did not penalize people who left to get married. They did not want to exercise that option.”

The couple, represented by attorney Daniel G. Marshall, took their fight to the California Supreme Court. Marshall petitioned for an original writ of mandamus to compel the issuance of the license. He argued that, as the church was willing to marry Davis and Perez, the state’s anti-miscegenation law violated their right to participate fully in the sacrament of matrimony, thus violating their First Amendment rights.

The final ruling delivered by Justice Traynor was 4-3 in favor of Perez.

While Marshall’s primary argument was one of religious freedom, in his opinion written for the majority, California Justice Roger Traynor focused not only on the First Amendment argument, but also on the fact that the California Civil Code that prohibited interracial marriage was sufficiently vague as to be unenforceable. Traynor questioned how much “negro” someone would need in their blood to lose their fundamental right to marry?

The opinion reads, “In summary, we hold that sections 60 and 69 are not only too vague and uncertain to be enforceable regulations of a fundamental right, but that they violate the equal protection of the laws clause of the United States Constitution by impairing the right of individuals to marry on the basis of race alone and by arbitrarily and unreasonably discriminating against certain racial groups.”

Lenhardt believes that Justice Traynor could be thought of as an early critical race theorist. “What he explores in the opinion was sort of a growing reluctance to see race as biological — to see it as a social construction and to challenge the legitimacy of the racial categories. I think this was unique for a court to do at the time.”

The impact of Perez v. Sharp extended far into the future.

Evan Wolfson, attorney and founder of Freedom to Marry, the leading organization in the fight for same-sex marriage equality, explains the arc from Perez to Loving, and Loving to Obergefell v. Hodges, the landmark Supreme Court case that legalized same-sex marriage. “To achieve Loving, someone had to go first, and that was Perez. And even with the beauty and power and correctness of Perez, it took another 19 years of struggle.”

But Wolfson cautions, “To really achieve change, we must understand that these changes don’t come by themselves. They come from civic engagement that combines the work of lawyers, with the work of public education, persuasion, political engagement. That is the arc from Perez to Loving to Baeher to Obergefell.”

Erik Mangrum served as a digital fellow at American Experience. He holds a Bachelor’s Degree in communications from Endicott College.

Published June 12, 2017.