Evangelicals and the American Presidency

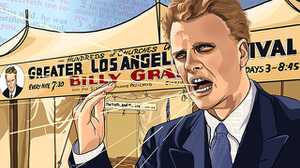

Billy Graham's unprecedented access to U.S. presidents ushered in a new era of evangelical influence in American politics.

Even in death, Billy Graham couldn’t escape politics.

When famed evangelist Billy Graham died in 2018, at age 99, Congress came to a standstill as his casket lay in honor under the U.S. Capitol Rotunda. Graham was the first religious leader and just the fourth civilian to receive the high tribute.

Lawmakers from both parties paid their respects and the nation’s three most powerful politicians—House Majority Leader Paul Ryan, Senate leader Mitch McConnell and President Donald Trump—spoke glowingly of Graham’s influence.

“Today we give thanks for this extraordinary life,” Trump said. “And it is very fitting that we do so in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol, where the memory of the American people is enshrined.”

Other Americans, particularly church-state separationists, found it less fitting. Elected officials should not endorse any religious figure, no matter his renown, they argued.

“Such a high government honor for someone solely for their work spreading an interpretation of one faith offends the spirit of our First Amendment’s guarantee that the government will not take actions that endorse or promote religion,” wrote Americans United for Separation of Church and State.

As Graham’s casket was moved to North Carolina, where his funeral was held and body buried, the debate fizzled. But in many ways, it was a fitting capstone to Graham’s political life. He brought evangelicalism to the corridors of power, drew high-praise from the many leaders he befriended and often trailed a debate about the proper role of religion in politics.

Famous for his soul-saving, country-crossing crusades, Graham became known as “the president’s pastor.” He met every chief executive between Truman and Trump and was a friend and confidante to several. But his closest political friendship, with Richard Nixon, was also his most costly.

The two men bonded over their dogged anti-Communism, and, as Nixon ran for president in 1960 and 1968, Graham offered political advice on how to court conservative Christians. He also extolled Nixon’s integrity and vouched for his character. After Watergate and the release of the Nixon tapes, the evangelist realized how badly he’d been misused.

“I felt like a sheep led to the slaughter,” Graham told William Martin, author of A Prophet with Honor: The Billy Graham Story. Martin called Graham’s association with Nixon “the most troubling and disappointing of his long and generally admirable career.”

Reflecting on his life, Graham said he had one big regret: he “would have steered clear of politics,” he told Christianity Today, the evangelical magazine he founded.

While Graham stepped back from partisan politics after Watergate, others rushed into the breach. He had shown that conservative Christians could build close relationships with the White House and planted a seed that later evangelical pastors would harvest.

Evangelicals made their influence felt in other ways, as well, particularly during presidential campaigns, when their votes provided a crucial constituency for any White House hopeful. Here are three moments in which white evangelicals played a key role in the race for the American presidency.

Kennedy in the lion’s den

In 1960, John F. Kennedy became the first Catholic to receive a major political party’s presidential nomination since Al Smith, a New York Democrat, in 1928. Many of Kennedy’s advisers believed anti-Catholicism had waned in the intervening thirty years. But by September of 1960, the “oldest American prejudice” had reared its ugly head. The bigotry was organized and tenacious, said Shaun Casey, author of The Making of a Catholic President.

“That’s what really scared them,” Casey said, referring to Kennedy’s advisers. “And at that point, they snapped back to the reality that they had to address this issue directly.”

According to one estimate, more than 360 anti-Catholic tracts and pamphlets circulated during the campaign. Many questioned Kennedy’s fealty to Rome, some accused the candidate of being a double-agent for the Vatican.

Kennedy accepted an invitation from the Greater Houston Ministerial Association, a group of some 300 Protestant pastors, just two months before the election. Some called it the candidate’s moment in the lion’s den; many agree it was the most important moment of his campaign.

“We can lose or win the election right there in Houston,” said Ted Sorenson, a Kennedy adviser.

In his prepared remarks, which were broadcast in Texas, Kennedy sought to assure the ministers that his allegiance to the Catholic Church was spiritual and that he would take no orders from any Catholic official, including the pope, as president of the United States.

“I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute,” he said, “where no Catholic prelate would tell the president (should he be Catholic) how to act, and no Protestant minister would tell his parishioners for whom to vote … and where no man is denied public office merely because his religion differs from the president who might appoint him or the people who might elect him.”

The speech was applauded, but the night’s real action took place during the question and answer session that followed. It had the feel of a shooting gallery, with the pastors firing questions at Kennedy about the views of his church on matters religious and political. One accused him of deferring to a cardinal’s orders and backing out of an interfaith dinner in 1947.

After denying the account, Kennedy challenged his opposition, saying, in essence: Is that all you got?

“I have been [in Washington, DC] for 14 years. I have voted on hundreds of matters, probably thousands, which involved all kinds of public questions, some of which border on the relationship between church and state,” he said.

“Quite obviously that record must be reasonably good or we wouldn’t keep hearing about the [interfaith dinner] incident.”

Ministers in the room applauded. Kennedy survived the lion’s den.

Jimmy Carter tells Jerry Falwell to ‘go to hell’

In 1976, Jimmy Carter introduced a new word into the political sphere: born again. The Georgia governor explained, as he ran for president, that he was an evangelical Christian, one of many in the South.

At the same time, GOP operatives saw an opportunity to recruit “separatist” Baptists like the Rev. Jerry Falwell to the party. The fundamentalist pastor from Lynchburg, Virginia put aside his misgivings about politics in 1979, when he co- founded the Moral Majority. One of the new group’s chief aims was defeating Carter.

Carter, Falwell argued, was on the wrong side of three issues taken up by his coalition: abortion, homosexuality and prayer in public schools. (Others, like the historian and Carter biographer Randall Balmer say the real issue was segregated Christian schools in the South.)

Then, during his campaign for re-election, Carter gave a fateful interview to Playboy magazine, in which he cautioned Christians about moral judgement.

“Christ says, Don’t consider yourself better than someone else because one guy screws a whole bunch of women, while the other guy is loyal to his wife,” Carter said.

Even he, the president acknowledged, “had committed adultery in my heart.”

Such beliefs—that all humans are sinners only redeemable through God —are common among Christians. But the Playboy interview gave evangelicals like Falwell a perfect excuse to abandon him.

“Like many, I am quite disillusioned,” Falwell told the media. “Four months ago the majority of the people I knew were pro-Carter. Today, that has totally reversed.” Pastors blasted Carter from the pulpit, questioning his judgement for granting an interview to a “salacious, pornographic magazine.”

Carter quickly realized the political damage done. “In ten days I dropped fifteen percentage points because of that interview,” he said. The evangelical president was deeply disappointed by the pile on from evangelicals, including Billy Graham, whom he had considered friends and co-believers.

Then Falwell spread a rumor that the president bragged about hiring LGBTQ people at the White House. Carter and others in the room denied Falwell’s account, according to Balmer’s book Redeemer: The Life of Jimmy Carter.

Meanwhile, Ronald Reagan and Republicans successfully courted evangelicals, while Falwell and others helped mobilize them. More than half of white evangelicals broke for Reagan, according to estimates, a reversal of the 1976 election.

Carter said the personal attacks on his faith had stung. After the election, while sitting in the Oval Office, he said, “I guess it felt bad when I heard Falwell say, ‘Atleast we’ll now have a real Christian in the White House.’” Reagan’s personal life, he was a divorced former Hollywood actor who rarely went to church or otherwise mentioned religion, would seem more at odds with evangelical values.

A few years later Carter was more defiant. “There is nothing a television evangelist can do to shake my faith,” he reportedly told United Press International. “Jerry Falwell can—in a very Christian way—as far as I’m concerned, he can go to hell.”

George W. Bush’s ‘Christ moment’

It was one of the most memorable moments of the 2000 Republican presidential primaries, and it happened by mistake.

Among the candidates, the competition for evangelical voters, by now a crucial bloc of the GOP, had been fierce, but no one had separated themselves from the field.

Then, at a GOP debate in December 1999, a few weeks before the Iowa caucuses, the moderator asked George W. Bush to name his favorite political philosopher. “Christ,” Bush answered quickly, “because he changed my heart.”

The moderator followed up: A viewer might ask how Jesus had changed his heart?

“Well, if they don't know, it's going to be hard to explain,” Bush said, squinting and shifting in his chair. “When you turn your heart and life over to Christ, when you accept Christ as a savior, it changes your heart and changes your life. And that's what happened to me.”

The next morning, Bush said he had misheard the question, which he thought was about the philosopher who had the greatest influence on his life. But by then the campaign’s “Christ” moment was rocketing through the media sphere, playing in loops on cable news as pundits debated whether Bush’s answer demonstrated shrewd politics or true piety.

Some evangelicals criticized the Texas Republican. ”To see Christ as a political philosopher is to lose sight of what we believe," said Rich Cizik, spokesman for the National Association of Evangelicals. "It seems more like a political statement, and there is always a temptation to use religious faith for partisan purposes.” Others questioned whether Bush’s policies as governor of Texas, such as widespread use of the death penalty, was sufficiently Christ-like.

For many conservative white evangelicals, however, especially those who didn’t pay much attention to politics, the certitude and clarity of Bush’s answer had a familiar ring. It was an unmistakable signal that Bush was “one of us” as one former high-ranking Southern Baptist said. For the son of an Episcopalian, Bush spoke fluent evangelicalese.

Bush was raised in the Episcopal Church, where he was an altar boy. When his family moved to Texas they attended a Presbyterian church, where George H.W. Bush would become a church deacon and elder. But George W. Bush cut his own spiritual path, which, by his own admission, included a chapter of prodigality. The scion of a political family, Bush was more interested in good times than God until middle-age, when, he said, a walk with Billy Graham changed his life.

As Bush tells the story in his campaign biography, A Charge to Keep, Graham spent the weekend with the Bushes at their Maine compound in Kennebunkport. One night, George H.W. Bush asked Graham to answer questions from the big group of family.

George W. Bush said he recalls Graham’s aura more than his answers. “He was like a magnet; I felt drawn to seek something different.” As the story goes, during a walk on the beach later that weekend, Graham pointedly asked Bush if he was right with God. Apparently, Bush wasn’t so sure, until that visit with Graham.

“Over the course of that weekend, Reverend Graham planted a mustard seed in my soul, a seed that grew over the next year,” Bush writes. “He led to the path, and I began walking. And it was the beginning of a change in my life.”

When Bush spoke about how Christ changed his life at that debate in 2000, it’s not a stretch to think he was talking about that walk on the beach with Billy Graham. In a life of shaping American politics, it was one of Graham’s most private and perhaps influential moments.

Daniel Burke is a contributing editor at Tricycle: The Buddhist Review and the former religion editor at CNN.