A Tale of Two Preachers

The fraught relationship between Martin Luther King, Jr. and Billy Graham.

In February of 1957, Martin Luther King, Jr. received a letter from a pastoral colleague envisioning how King might someday join forces with a famed, white evangelist from North Carolina: “I even dare to dream, beyond this present day of crisis in Montgomery, of a time when you might appear with Billy Graham in a number of cities, North and South.”

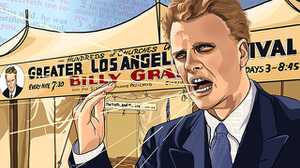

For a decade, Graham had toured the United States as well as the United Kingdom, Germany, Scandinavia and France and took to enormous crowds what he called his religious crusades—mass rallies in which he proclaimed the Gospel and asked individuals to commit to a “life in Christ.” A 1954 TIME Magazine cover story called Graham “the best-known, most talked-about Christian leader in the world today, barring the Pope.”

By February 1957, King had also made the cover of TIME. The magazine celebrated the “scholarly, 28-year-old Negro Baptist minister” as “one of the nation’s remarkable leaders of men.” TIME marveled at King’s leadership of the Montgomery bus boycott, which had just recently come to a close with the Supreme Court ordering the end of bus segregation. “King’s impact,” TIME noted, “has been felt by the influential white clergy, which could—if it would—help lead the South through a peaceful and orderly transitional period toward the integration that is inevitable.”

Graham, for his part, lauded King’s activism. Asked by a reporter two months later about the best means of ending segregation, Graham said, “it’s going to have to be done by setting an example of love, as I think Martin Luther King has done in setting an example of Christian love.”

After returning from Europe with new-found international fame, Graham set his sights on New York City. His Times Square crusade began on May 15, 1957, with its Madison Square Garden venue filled to capacity from the first day. Two days later, as Graham preached to thousands in New York, King gave the closing address at the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom, a demonstration at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. to mark the third anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education and highlight southern states’ refusal to desegregate schools in compliance with that ruling. At 30,000 people, it was King’s largest live audience to date. Following his address, the New York Amsterdam News pronounced him “the top Negro leader.”

Weeks into Graham’s crusade, more than 18,000 people were still flocking to the big show in Manhattan every night. But Graham was troubled that expressed support from Black New York City churches and the inclusion of several Black pastors on crusade committees did not translate to his audience, which was overwhelmingly white. After a phone conversation between Graham and King, an associate evangelist with Graham’s organization wired King an invitation to speak at the crusade. King accepted and gave the night’s opening prayer on July 18, 1957, intoning the ideal of “a brotherhood that transcends race or color.”

King wrote to Graham afterward, hopeful of striking up an alliance: “You have courageously brought the Christian gospel to bear on the question of race in all of its urgent dimensions,” King said, stressing to Graham that “you, above any other preacher in America can open the eyes of many persons on this question. Your tremendous popularity, your extensive influence and your powerful message give you an opportunity in the area of human rights above almost any other person that we can point to. Your message in this area has additional weight because you are a native southerner.” Following on these first demonstrations of mutual admiration, Graham and King talked several times privately about the possibility of further collaboration.

The next summer, King received troubling news: Graham was holding a crusade in San Antonio, Texas, and Price Daniel, the state’s staunchly segregationist governor, was set to introduce him. “Dear Brother Graham,” King wrote in an urgent wire message. “Under the circumstances we would hope that Governor Daniel’s participation on your program might be avoided. If this is not done, we urge you to make crystal clear your position on this burning moral issue. For any implied indorsement [sic] by you of segregation can have damaging effect on the struggle of Negro Americans for human dignity and will greatly reduce the importance of your message to them as a Christian Minister who believes in the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man.”

Graham appeared with Daniel onstage as planned. One of Graham’s advisors then wrote back to King. “Billy Graham has never engaged in politics on one side or the other,” replied the advisor. “We were surprised to receive your telegram and learn of your feeling toward the Governor of the Sovereign State of Texas. Even though we do not see eye to eye with him on every issue, we still love him in Christ, and frankly, I think that should be your position not only as a Christian but as a minister.”

The tenuous alliance between Graham and King continued to fray in coming years. In October 1960, King participated in his first sit-in. Together with a group of Black students, he asked to be seated at a segregated restaurant in Atlanta, Georgia. All of them were arrested for violating an anti-trespassing law and all chose to refuse bail and accept prison time in return. Before they were sentenced, King declared that choosing prison was a call to the conscience of white America. “If you find it necessary to set a bond,” King said to the judge, “I cannot in all good conscience have anyone go buy my bail. I will choose jail rather than bail, even if it means remaining in jail a year or even ten years. Maybe it will take this type of self-suffering on the part of numerous Negroes to finally expose the moral defense of our white brothers who happen to be misguided and thusly awaken the dozing conscience of our community.”

Graham happened to be in Atlanta the next month and was asked what he thought of the sit-ins. “I do believe that we have a responsibility to obey the law,” he told a reporter. “Otherwise, you have anarchy. And, no matter what that law may be—it may be an unjust law—I believe we have a Christian responsibility to obey it.” But Graham felt differently about the law when it came to desegregation. “I am convinced that forced integration will never work,” Graham wrote in a United Press International column earlier that year. “You cannot make two races love each other and accept each other at the point of bayonets. The Supreme Court can make all the decisions it feels are necessary, but unless they are implemented by goodwill, love and understanding, great harm will be done.”

In December 1961, King joined a march for desegregation in Albany, Georgia and was once again arrested, drawing national media attention. Graham could agree that “Jim Crow must go,” but he did not condone direct action. “I am convinced that some extreme Negro leaders are going too far and too fast,” he told reporters at a press conference a few months later in Chicago. With this statement he made clear his priority to save the souls of the 700,000 predominantly white audience members that attended his crusade there over two and half weeks in May and June.

On Good Friday in 1963, King led a march from Birmingham, Alabama’s 16th Street Baptist Church, in defiance of the city’s injunction barring protests. As he approached a police barricade, police hoisted up King by his belt, shoved him in a paddy wagon and took him to prison, where the city held him in solitary confinement.

Graham was among the many of King’s friends and foes to comment on the Birmingham marches and the civil rights leader’s imprisonment. Speaking to the New York Times, Graham urged his “good personal friend” to “put the brakes on a little bit.” Graham expressed “serious doubt … that the Negro community there supports it.” To Graham, “the timing [was] questionable.”

Troubled by what the press reported, King made notes in the margins of newspapers smuggled into his cell for a statement that soon became one of his most widely read—across the country and ultimately around the world.

“I have been so greatly disappointed with the white church and its leadership,” King lamented in his now famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” “When I was suddenly catapulted into the leadership of the bus protest in Montgomery, Alabama, a few years ago, I felt we would be supported by the white church. I felt that the white ministers, priests and rabbis of the South would be among our strongest allies. Instead, some have been outright opponents, refusing to understand the freedom movement and misrepresenting its leaders...I have watched white churchmen stand on the sideline and mouth pious irrelevancies and sanctimonious trivialities."

King’s early hopes that Graham would be a key ally did not come to pass. Civil rights and evangelical Christianity did not find mutual ground. And the schism between the two ministers’ methods would persist long beyond King’s assassination five years later. “He had his demonstrations in the street, while I had mine as lawful religious services in stadiums,” Graham would say in 1996, long after King’s death. Billy Graham died in 2018 at age 99, the 50th anniversary of the year King was murdered at 39.