Radios across the world were tuned in on August 14, 1936 when nine working-class boys from the University of Washington took gold at Hitler's Olympics. The Nazi dictator watched from the stands as the UW rowers found their swing—or perfect harmony—after years of preparation during the worst times of the Great Depression.

-

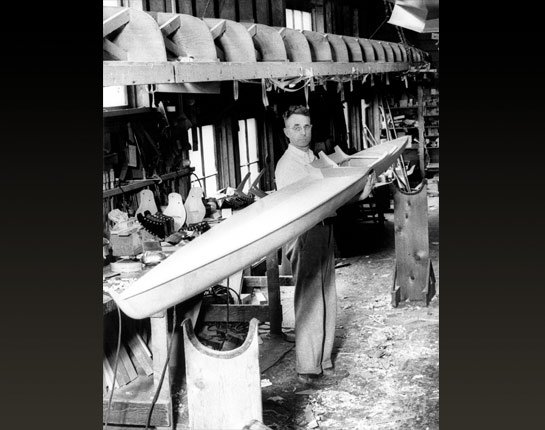

George Pocock learned the art of building from his father, who handcrafted the shells for elite Eton rowers in England. In 1912, Pocock was recruited to build racing shells for the University of Washington and other collegiate rowing programs around the country. Pocock was also a mentor to generations of Washington rowers.

Credit: Getty Images -

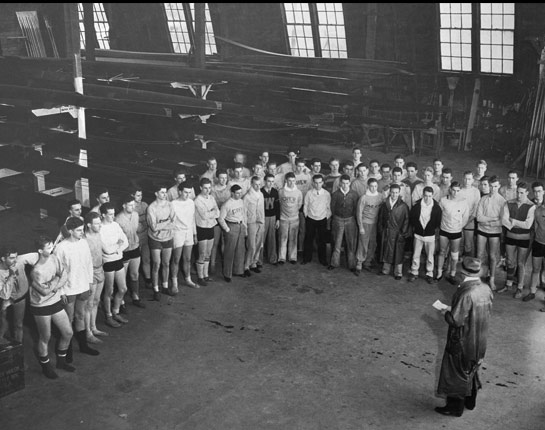

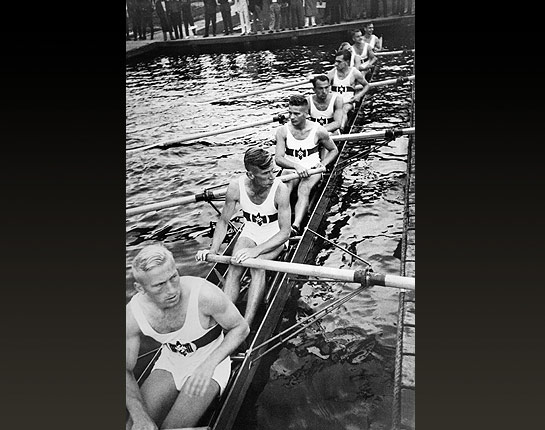

University of Washington head coach Al Ulbrickson speaks with a pool of 50 potential rowers in January 1934, as they vie for a coveted spot in the varsity boat that could make it to the Olympics. Ulbrickson created competition between the boys and tensions would rise in the shell house.

Credit: Bettmann/Corbis -

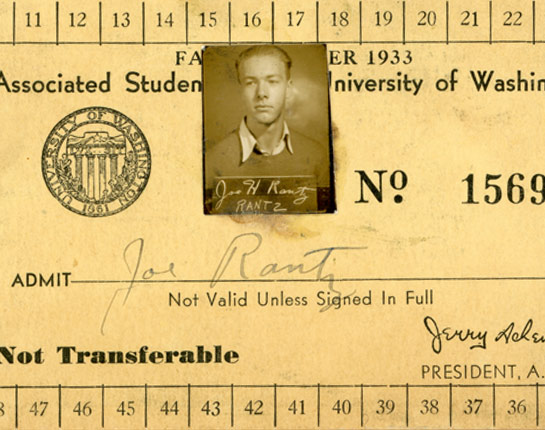

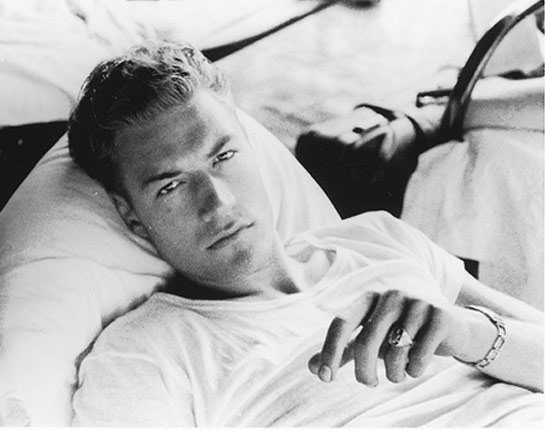

Joe Rantz enrolled at the University of Washington in 1933, pictured here on his freshman student ID. In Rantz's time there were no scholarships for rowers, but the school would find you a campus job. Rantz would work at a store on campus as well as at the YMCA as a night janitor to help pay for school.

Credit: The Joe Rantz Family -

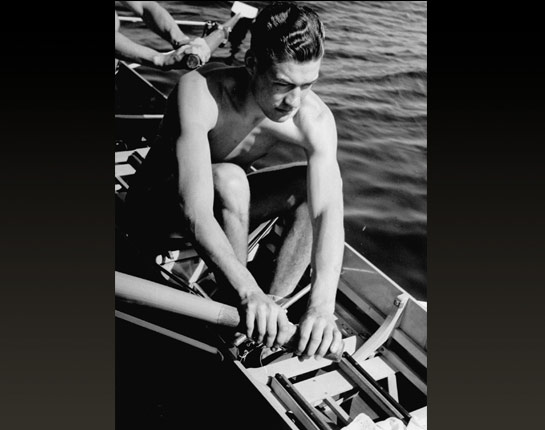

Upperclassman Bobby Moch emerged as a smart -- and determined -- coxswain. Since 1978, Coxswains have used an amplification system commonly called a CoxBox, but in the 1930's Moch used a simple megaphone to make calls to his rowers.

Credit: The Bobby Moch Family -

Don Hume was a standout freshman stroke oar when he joined the University of Washington team in 1935. Ulbrickson soon realized that Hume and some of his fellow freshmen teammates would have to be factored into the potential Olympic boat for 1936.

Credit: The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images -

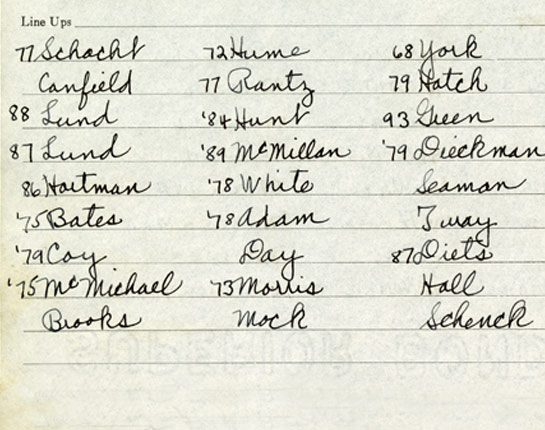

In March 1936, Ulbrickson records the line-up he believes will be the winning combination for the 1936 Olympics. Column two in his book lists the boys he would assign to the varsity boat, starting with sophomore Hume as the stroke oar, and ending with junior Roger Morris in seat number one. He listed the coxswain -- senior Bobby Moch -- at the bottom of the column.

Credit: University of Washington Archives -

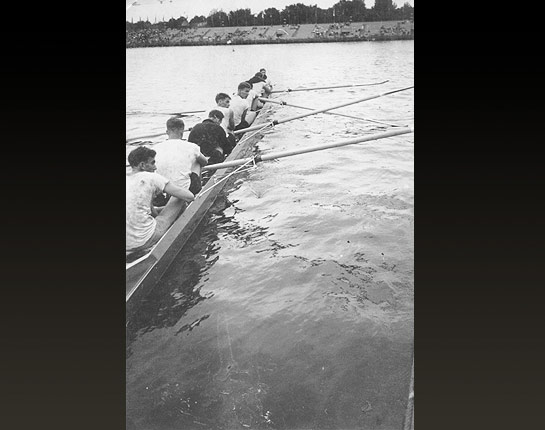

The Washington varsity boys practice in Poughkeepsie, New York on June 15, 1936 despite heavy winds. They would race for the national championship on June 22.

Credit: Bettmann/Corbis -

On June 22, 1936 the varsity boys beat rival Cal in Poughkeepsie and advanced to the Olympic trials in Princeton in hopes of qualifying for Berlin. UW's JV and Frosh (freshmen) boats won as well. Ulbrickson "swept the Hudson" for the first time and his team was one step closer to the '36 Olympics.

Credit: Poughkeepsie Public Library District -

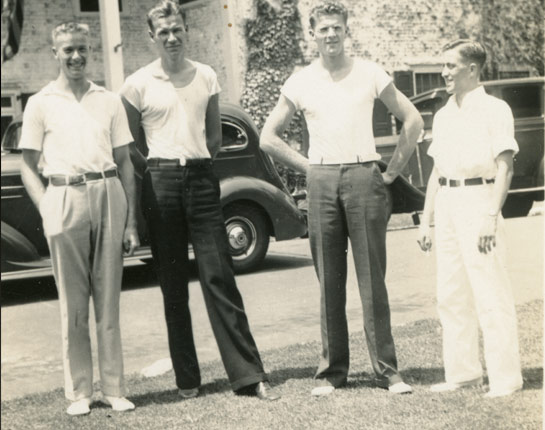

Joe Rantz, Jim "Stub" McMillin, Chuck Day and Bobby Moch take a break from the water in 1936 in New Jersey during the Olympic qualifying trials. Despite earlier competition back in Washington, friendship and trust was necessary to make the boat the best as it could be.

Credit: The Bobby Moch Family -

On July 5, 1936 the UW varsity rowing team had won the Olympic trials, and they would soon sail for Germany to compete for Olympic gold in Berlin. Here, head coach Al Ulbrickson directs his boys during practice on July 10, 1936.

Credit: Associated Press -

When the boys arrived in Germany they didn't stay in the Olympic Village, but rather in these police barracks in the town of Kopenick, where the rowing Olympic competitions would be held.

Credit: The Bobby Moch Family -

The little village of Kopenick is located southeast of Berlin along a lake named the Langer See. Unknown to the athletes, the town already had a dark history. The Nazis had rounded up Jews and political opponents in the town in 1933, tortured them, killed many, and then dumped their bodies into the local waterways where the boys would row for the gold.

Credit: The Joe Rantz Family -

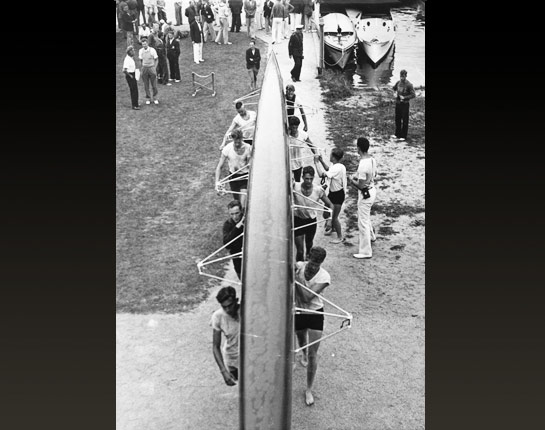

The boys carry their 62-foot racing shell on August 12, 1936 in Germany. Despite a sickly Don Hume, the boys won first place in their preliminary heat for the Olympic medaled race and now had 48 hours to rest until the pinnacle race on August 14.

Credit: The Bobby Moch Family -

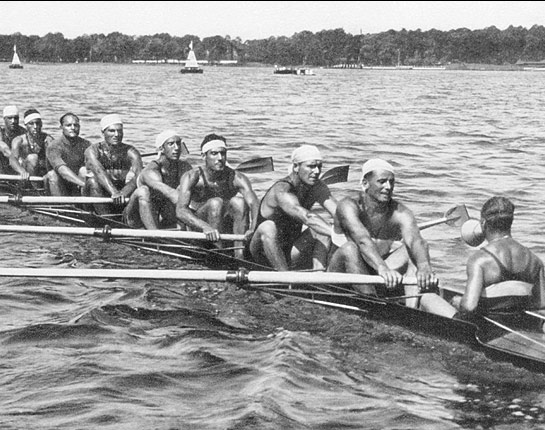

The German government had subsidized training for their Olympians, and the rowing team was no exception. The Nazis had searched the country for the best oarsmen and gave them uninterrupted training time for over a year before the 1936 games.

Credit: Getty Images -

The Italian team the Americans faced for Olympic gold in 1936 had been together as a team for more than a decade, were very large and physically powerful, and had logged the most time in the water.

Credit: Getty Images -

Pocock and Ulbrickson worried about the British team, pictured here, and their entry into the Olympic race. The team included Oxford and Cambridge rowing veterans and had a history of Olympic gold medal victories.

Credit: Way's Rare & Second Hand Bookshop, Henley -

Stroke Don Hume had remained sick in bed for much of his time in Germany. The morning of the big race Ulbrickson declared Hume too sick to row. Hume's teammates, however, told the coach they couldn't do it without him, so Ulbrickson relented and Hume was back in.

Credit: The Bobby Moch Family -

As the final eight-oared race approached, Ulbrickson had one last huddle with the nine boys in the boat. The other competitors wore their sleek Olympic uniforms while the UW boys chose instead to wear track shorts and old t-shirts for fear of getting their new uniforms dirty. Despite having the worst lane number, the boys came from behind to win Olympic gold with Italy in second place, Germany in third, and Great Britain coming in fourth.

Credit: The Joe Rantz Family -

Eight of the original nine Olympic champions returned to the University of Washington and remained undefeated in their 1937 season. Moch had graduated, but went on to coach for the University of Washington soon after.

Credit: The Ulbrickson Family Collection and Rowing Archives.