In 1910, the Big Burn tore through the Northern Rockies in Idaho and Montana, consuming more than three million acres in 36 hours. Browse a photo gallery of the men who fought the Big Burn and helped make the U.S. Forest Service what it is today.

-

Theodore Roosevelt took an interest in the preservation of America's wild lands. As president, Roosevelt appointed his friend and leading forestry expert Gifford Pinchot (pictured here on the Mississippi with Roosevelt) as chief forester of the newly formed U.S. Forest Service in 1905.

Credit: Harvard University Library -

In tripling the acreage of U.S. National Forest land to more than 300 million acres, Roosevelt and Pinchot aimed to not lock away all timber, but to regulate the amount that could be harvested in a sustainable manner.

Credit: U.S. Forest Service -

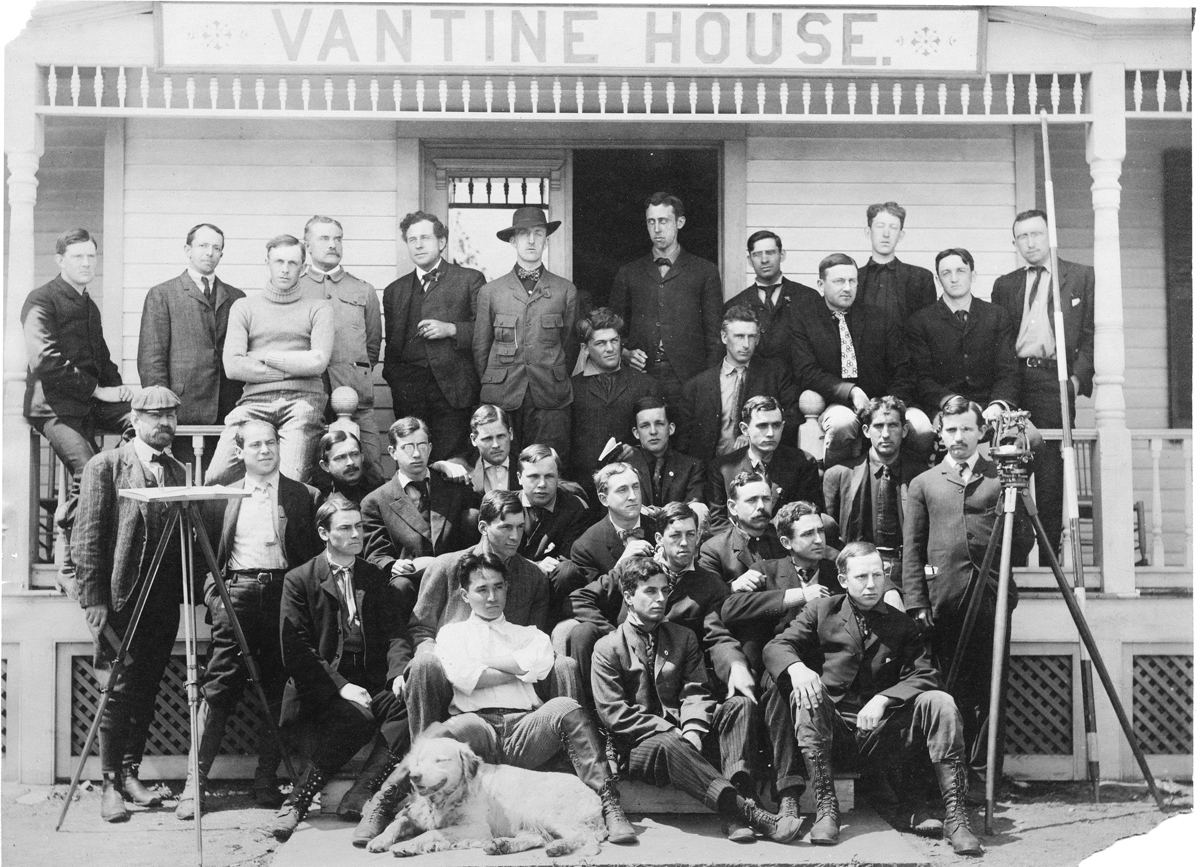

In 1900, Gifford Pinchot founded America's first school of forestry at his alma mater, Yale University. Several members of the class of 1905, pictured here, joined Pinchot in the West.

Credit: Yale Library Archives & Manuscripts -

Although Pinchot (center) was the son of a wealthy timber merchant, one of Pinchot's first students said the leader made them "feel like soldiers in a patriotic cause" to protect the nation's forests. Yellowstone National Park, 1906.

Credit: Grey Towers -

The new U.S. Forest Service rangers admired Pinchot, whom they called "G.P.," and willingly accepted the nickname of "Little GPs." Challis National Forest, Idaho, 1907.

Credit: National Archives -

Rangers in Montana, Idaho and South Dakota were each responsible for monitoring almost 200 square miles of National Forest. Cabinet National Forest, Montana, 1909.

Credit: Forest History Society -

In the dry summer of 1910, Forester William Greeley warned his rangers to "strengthen the patrol, and retain a strong guard," because the humidity "had dropped to the level of the Mojave Desert."

Credit: Forest History Society -

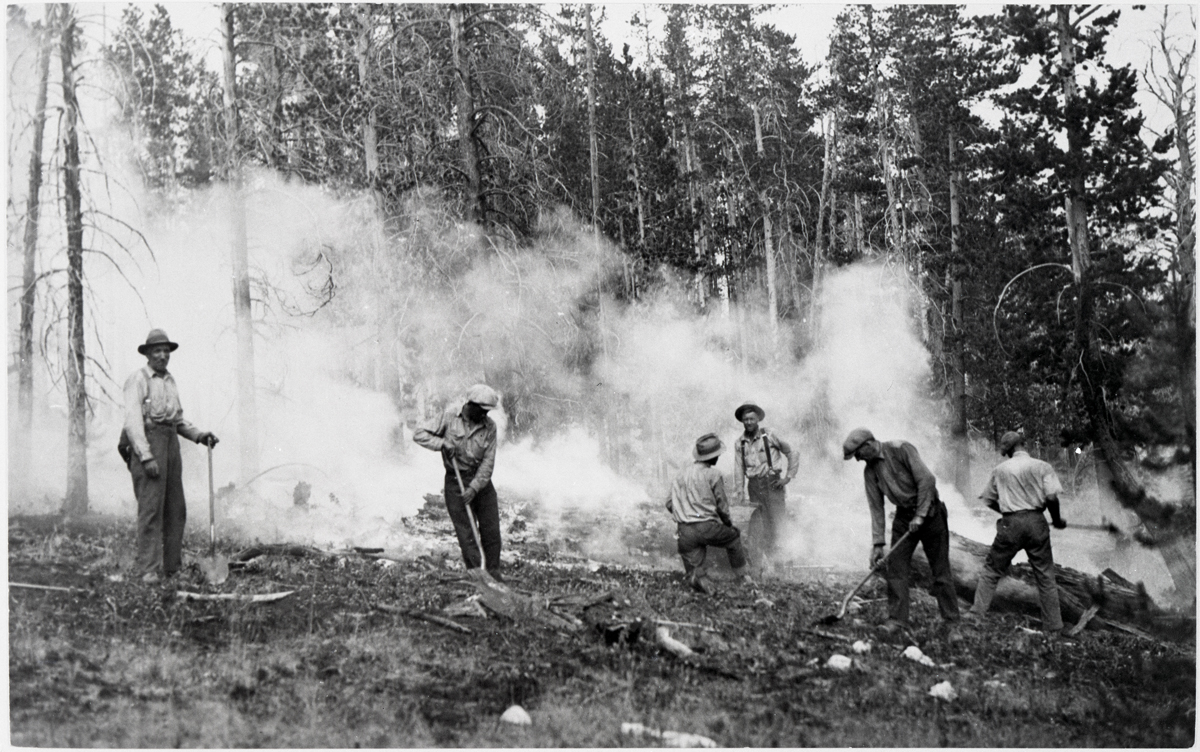

In July 1910, a violent lightning storm triggered nearly 1,000 fires across 22 forests in the Northern Rockies. Beaver Creek, Clearwater Forest, Idaho, 1910.

Credit: Museum of North Idaho -

Crews worked tirelessly to protect frontier towns from the fires raging across Montana and Idaho. But with only 500 rangers employed nationwide in 1910, the Forest Service was critically understaffed.

Credit: University of Montana Library -

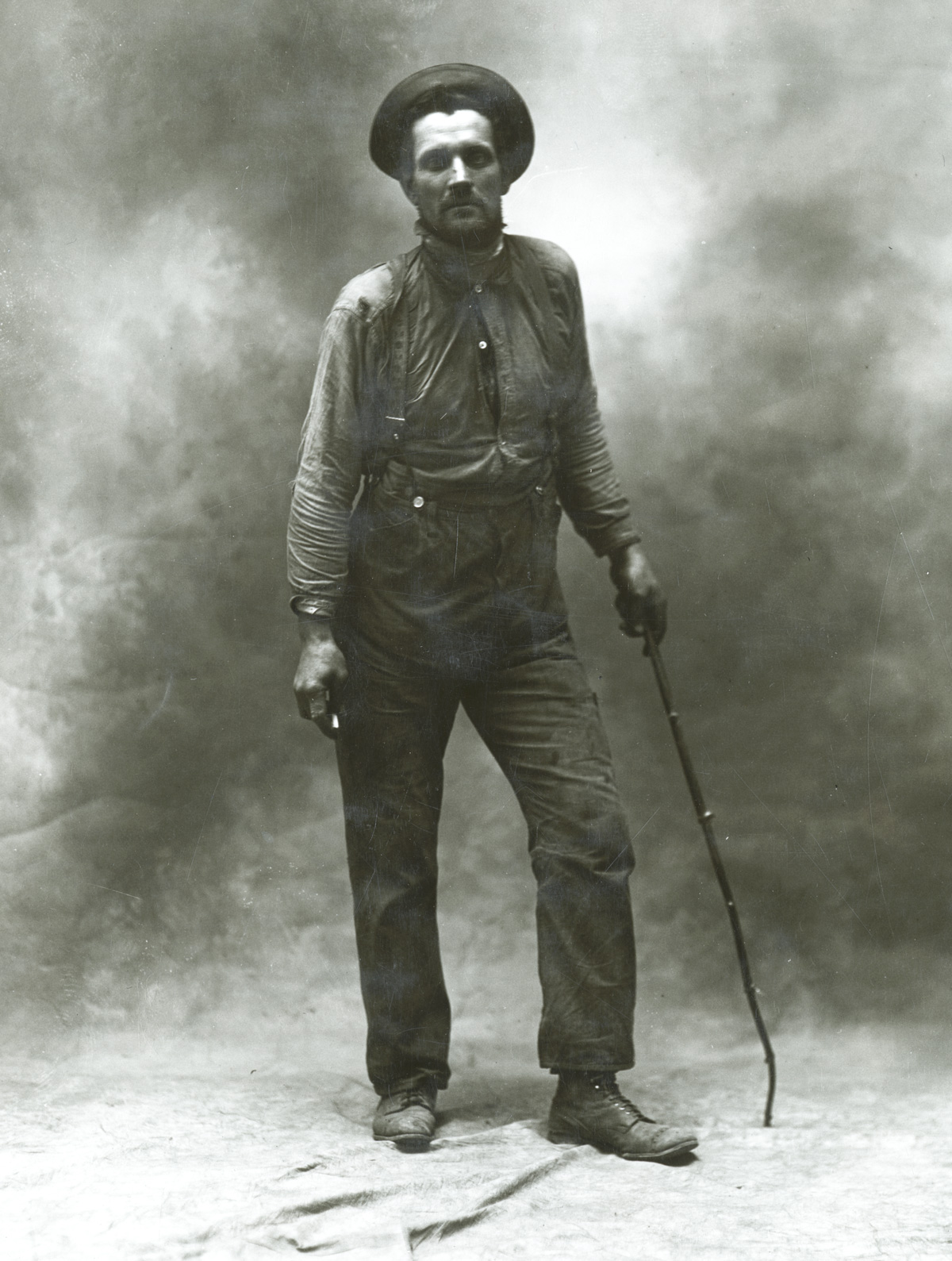

Desperate for manpower to help fight the fires, the USFS picked men off the streets of Idaho and Montana. They came ill-dressed and poorly equipped to fight fire.

Credit: Museum of North Idaho -

Members of the African American 25th Infantry, known as the Buffalo Soldiers, saved Avery, Idaho from being consumed by the inferno. An Avery resident later told newspaper reporters, "My whole attitude about the black race has changed as a result of what I've seen and witnessed from these fellows."

Credit: Museum of North Idaho -

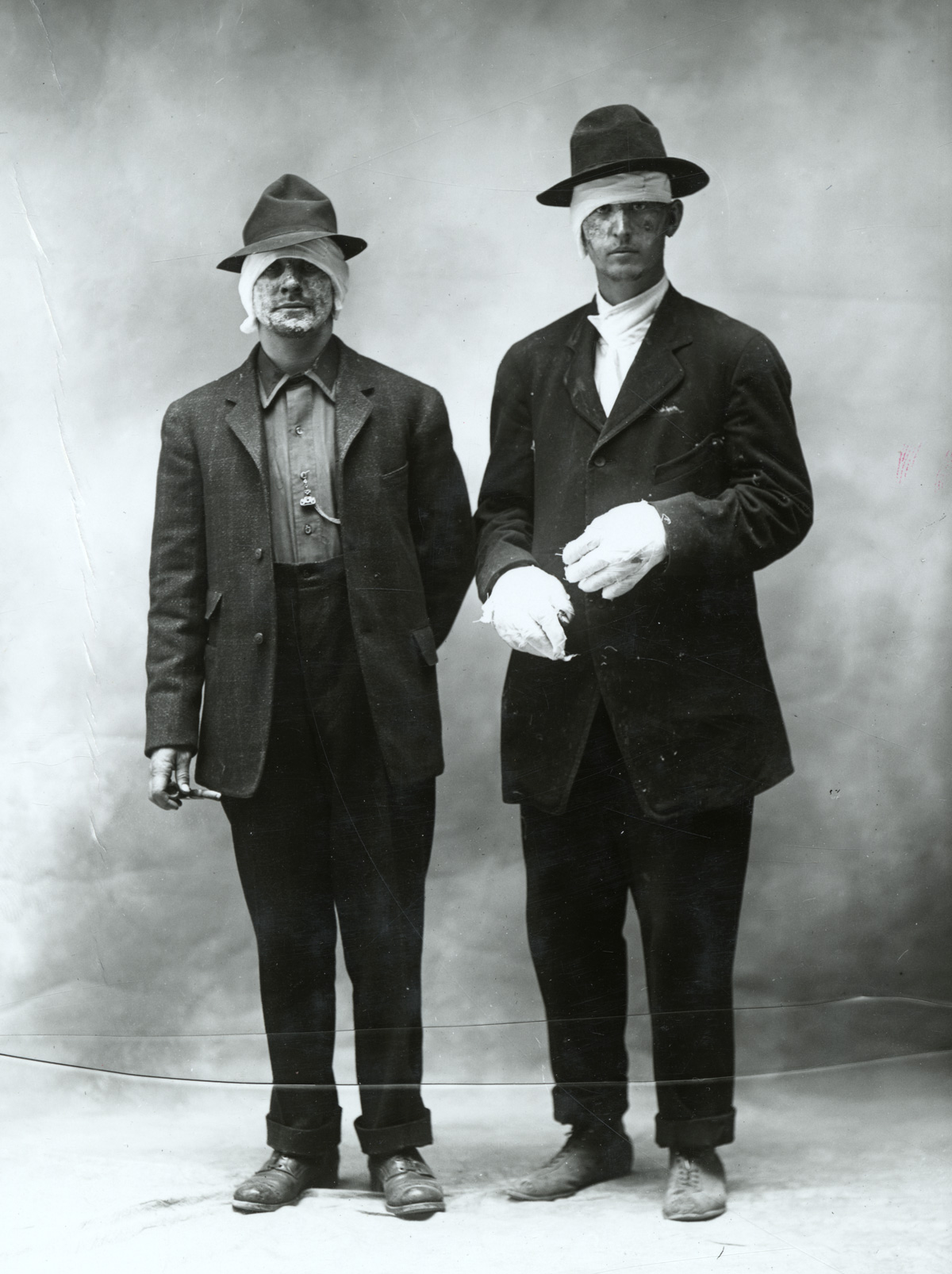

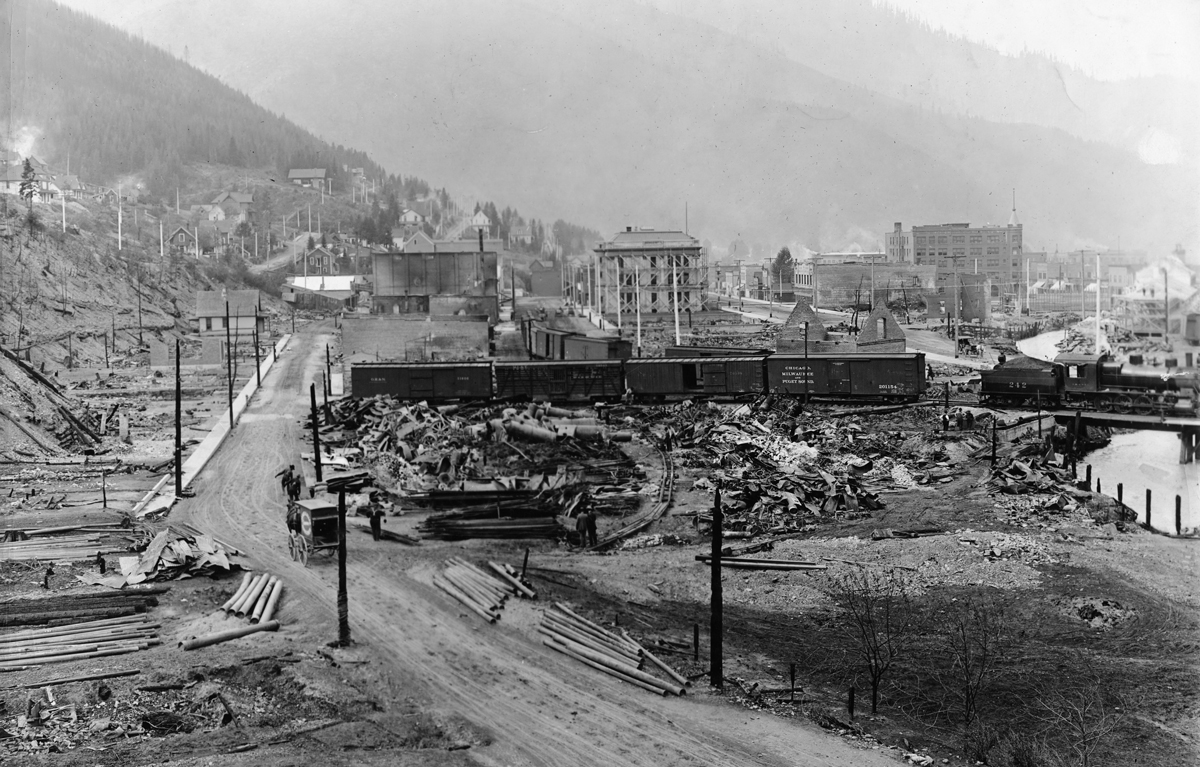

The Big Burn consumed over 3 million acres of the region's drought-stricken land in just 36 hours and killed at least 78 men. Several more would die from related complications in the weeks and months that followed.

Credit: University of Idaho -

In the aftermath of the Big Burn, the men who fought and died in the fire became national heroes. An outpouring of public support for the Forest Service helped push Congress to direct more funding and resources towards the young organization.

Credit: University of Idaho -

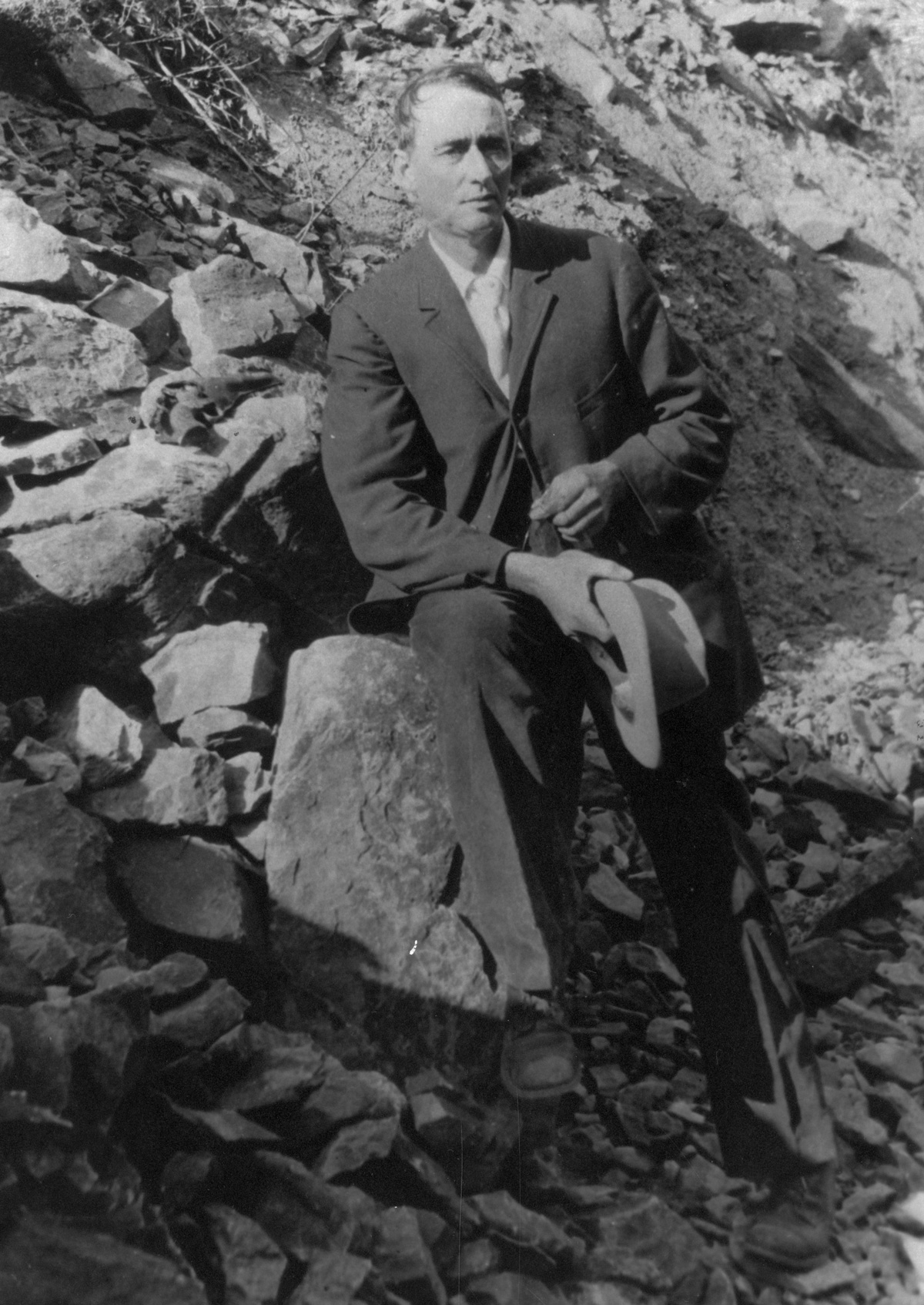

During the Big Burn, ranger Ed Pulaski urged his men to shelter inside an abandoned mine shaft. All but six of his 45-man crew survived, though Pulaski's injuries would plague him for the rest of his life.

Credit: Wallace Mining Museum -

Gifford Pinchot estimated that $1 billion worth of timber had been lost in the Big Burn. Park rangers pose by a trail during cleanup after the 1910 fires.

Credit: U.S. Forest Service Region 1 -

In the weeks after the Big Burn, thousands of people were left without homes. The soot from the inferno darkened the skies over Boston, and a layer of ash formed on the ice of Greenland.

Credit: Museum of North Idaho