The City of Boston Is Out of Control

In 1974, Boston’s schools were ordered to desegregate. Things got ugly, fast.

This article is the sixth in a series called A Thousand Words, where we feature an interesting image from one of our films alongside an essay about why that picture is worth, well, a thousand words.

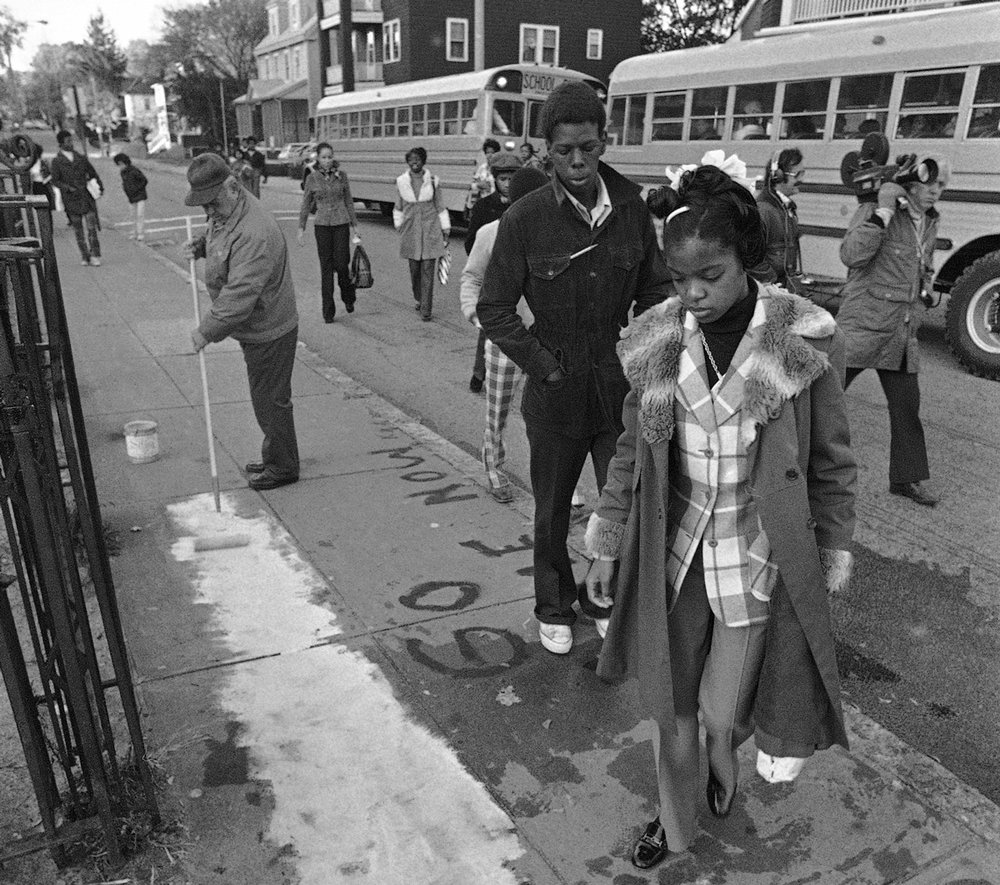

The photograph contains multiple figures but foregrounds two. Both high school students, eyes downcast, they tread on what remains of a spray painted message, his feet covering part of the phrase “go home.” Below the photo, when it appeared in the October 22, 1974 edition of the Boston Globe, was a caption: “Workman is busy cleaning up derogatory inscription written outside Hyde Park High School as pupils arrive for yesterday’s morning session.”

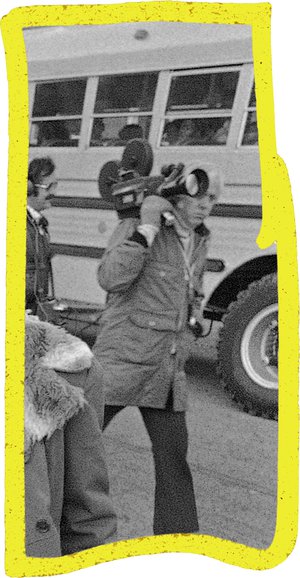

On that Monday morning in late October, Boston was entering its sixth week of court-ordered school busing, a drama marked by escalating racial violence that drew the attention of media outlets around the world. Intended to integrate the city’s public schools, the busing plan also revealed Boston’s darkest undercurrents. “What we prayed wouldn’t happen has happened,” the Globe’s editorial writers remarked in an opinion piece, two weeks before this image was captured. “The city of Boston is out of control.”

Black activists had hoped for a far different outcome when they began their campaign to desegregate the Boston public schools two decades earlier. Deploring the subpar education available to their children, those activists were routinely thwarted in their efforts to improve it. Despite drawing thousands of participants, several school boycotts received only short-lived attention, and Black candidates for the Boston School Committee—the group that decided how public school resources would be allocated—were routinely defeated.Activists were hopeful when, in 1965, Massachusetts adopted a Racial Imbalance Act requiring schools to address segregated enrollment, but Boston’s School Committee refused to comply with the Act for years.

By 1972, “the black community in Boston has tried everything,” journalist Farrah Stockman told American Experience. “They've tried the ballot box. They've tried direct action. They've tried the state house. And really it hasn’t worked. None of it has worked. So, some of them felt it was time to do the last option, which was the court system.” In March of that year, NAACP lawyers filed the Morgan v. Hennigan complaint challenging the city’s public schools’ racially discriminatory practices. Morgan v. Hennigan pointed to myriad instances of educational inequity: dilapidated facilities, overcrowding, an obfuscatory school feeder system, all deliberate efforts to separate the city’s white and Black students.

Meanwhile, when the Boston School Committee failed to address the racial imbalance in the public schools, the Massachusetts Board of Education developed a desegregation plan. That plan prescribed busing thousands of middle and high school students between white and Black neighborhoods. The state’s Supreme Court ordered the plan to be enacted by September 1974. Then in June 1974, district judge W. Arthur Garrity found in the Morgan v. Hennigan plaintiffs’ favor, writing in his decision “that the defendants have knowingly carried out a systematic program of segregation affecting all of the city’s students, teachers and school facilities and have intentionally brought about and maintained a dual school system.” Garrity also ordered the Boston School Committee to comply with the Massachusetts Supreme Court directive.

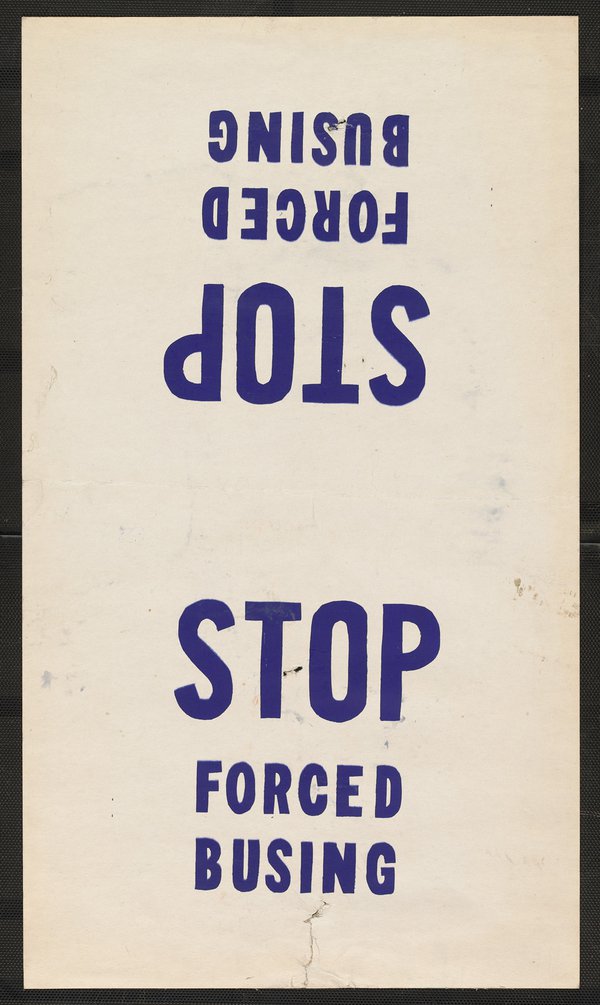

The African-American community’s response to the busing plan was ambivalent. In many cases, their children would now simply be sent from one low income area of the city to another, all with inadequate schools—achieving integration, but not the actual objective of a better education. Resistance among some white Bostonians, however, was swift and aggressive. Says Stockman, “some people really didn’t want to put their kids on a bus to another neighborhood. They were terrified. They didn’t own a car. If something happened, they would have a hard time getting there. Others were, quite frankly, very racist, and they did not want their child to go to school with someone from another ethnic group.” Months of anti-busing protests culminated in a 10,000-person-strong rally in Boston’s Government Center just before the first day of school. An irate crowd attempting to ambush Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy shattered a plate glass window as he was rushed away from City Hall Plaza.

Once the school year was underway, that unrest carried over to the classroom. Hyde Park High School—which now had hundreds of new students being bused in from the poor, predominantly Black Dorchester and Mattapan neighborhoods to Boston’s mostly middle income Hyde Park, became a battle zone. Buses carrying Black students to the school were stoned as they passed through gauntlets of furious neighborhood residents. During the first week, a car near the school was reported displaying a “KKK Thursday” sign. The next week, Hyde Park became the first school ordered by Boston School Superintendent William L. Leary to close after fighting broke out in the overcrowded cafeteria, leading to multiple student injuries. Police officers began patrolling the hallways.

Events at the school continued to escalate. A group of young white men were arrested with Molotov cocktails nearby. Two Black students were sprayed with mace while walking home. Then on October 15th, racial violence at Hyde Park High left eight students seriously injured, prompting the Governor of Massachusetts to mobilize the National Guard.

The media made Boston’s most fractious integration incidents into frontpage, nightly news stories. That coverage was how students in Charlotte, North Carolina came to reach out to their counterparts at Hyde Park, after launching a letter writing campaign to the Globe imploring Bostonians “to give integration a chance to work.” Representatives from Charlotte’s biracial student committee invited their Boston counterparts to come and learn from their own desegregation experience.

On the day this photo was taken, four Hyde Park students—two Black and two white—left for Charlotte to tour that city’s public schools. “We want to help,” Barbara Steer, one of the Black students, told the Globe. “I’m really looking forward to finding out what Charlotte did to get over the pains of school integration.” Her white classmate Linda Lawrence speculated about the cause of the ongoing discord. “Up here, Blacks have never really had to deal with whites, and whites never had to deal with blacks, so they’re scared of each other.” Of their fact-finding mission, Lawrence noted with incredulity, “I never thought I’d be going South for a lesson in racial relations.”

At American Experience we're always coming across photos from the past that we can't stop thinking about—images that are worth a thousand words.