We Were Never Meant to See this Photograph

An amazing flea market find reveals the scene at Casa Susana—a safe haven for transgender women and crossdressing men

This article is the fifth in a series called A Thousand Words, where we feature an interesting image from one of our films alongside an essay about why that picture is worth, well, a thousand words.

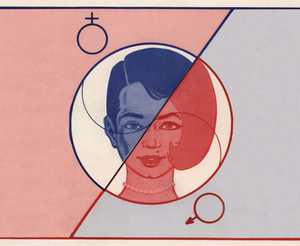

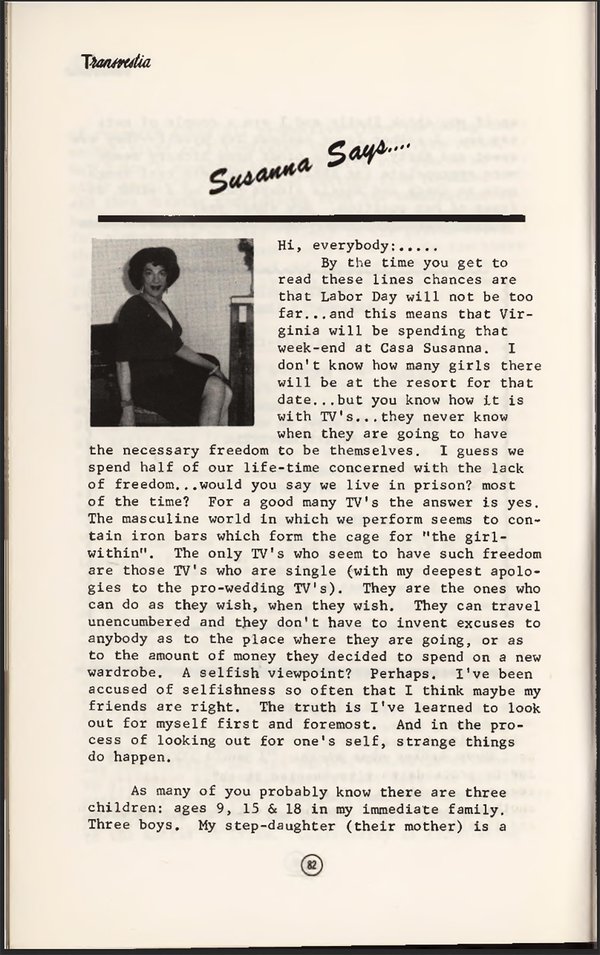

That we are able to view the photograph at all is sheer happenstance. An intimate portrait, the image was never intended for an audience beyond its subject and her close–knit inner circle. But in 2004, an antiques dealer named Robert Swope came across it, and 339 others, inside an old box at Manhattan’s 26th Street flea market. While some of the photos were loose, the majority were carefully organized into three albums, with a business card glued to the cover of one identifying the albums’ owner: “Susanna Valenti, professional transvestite.” It is Susanna in the photograph smiling coyly at the camera, as though both wanting to be seen, and not.

Swope described his flea market find in a foreword to a collection of the photographs that was published a year later: “I felt electrified. I had never seen anything like this that had not been clearly orchestrated as a parody or joke, and my instincts told me this was neither…Here were photos documenting everyday women, going about their everyday lives—except that these women were men who probably lived as truck drivers, accountants or bank presidents during the week.”

Shortly after the book’s publication, Swope was contacted by a doctoral candidate at the University of Michigan working on a dissertation about transvestism in post-World War II America. Robert Hill solved the mystery of Swope’s discovery, and filled in the photos’ backstory. The images in Susanna’s albums were taken between the late 1950s and late 1960s, many of them in and around an upstate New York retreat for cross-dressing men and transgender women. The retreat’s proprietors were Susanna—who went by the name Tito Arriagada during her weekly, public-facing life—and her wife Marie. The two had met when Susanna patronized Marie’s wig shop on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan.

At the time, Marie was already renting out bungalow cabins on her property in Jewett, New York, a few hours north of the city. Now, she and Susanna began to run a more exclusive retreat after those first guests left, calling it the Chevalier d’Eon, after an 18th-century French cross-dresser and spy. In the summer of 1963, Susanna and Marie moved their operation to a new property 10 minutes away in Hunter, New York, and christened it Casa Susanna.

Under Susanna and Marie’s stewardship, the slightly run-down, three-story house in the Catskill Mountains became a unique kind of bed and breakfast. Casa Susanna offered makeup, hair, wardrobe and comportment tutorials and 150 acres on which guests could roam freely “en femme,” as they called it. For many of the visitors, it was the first time they had ever been able to become these versions of themselves around others.

Susanna first advertised her eponymous resort in 1960 in Transvestia, an underground mail-order journal dedicated to male-to-female crossdressing. The magazine, which ran for over 20 years, was the first periodical in the United States to provide an early space for transgender community formation. “This is it, friends! At last it’s happened,” Susanna announced. “How would you like a place where you could take all your lacy panties, pretty slips, highest heels, nicest perfume and prettiest dresses and wear them not only undisturbed and unafraid but in the company of understanding people and others of the same kind?”

Most of the guests made the three-hour drive to Casa Susanna from New York City, but a few, having learned of the resort through Transvestia or word-of-mouth, came much farther in search of sanctuary, and themselves. Australian Katherine Cummings, born John Cummings, recalled her experience of visiting Susanna’s property in her 1986 memoir, Katherine’s Diary. “That first weekend at the d’Eon Resort was like stepping through a door into another universe, a universe where I could be Katherine in the open air,” she wrote. “It was an amazing, emancipating, unforgettable experience. After years of hiding behind locked doors, venturing out only after dark and not daring to speak in case my voice betrayed me, I was suddenly liberated into a society where I was not only tolerated but understood and welcomed.”

Documenting their new-found freedom was an important part of the Casa Susanna experience. Photographs were one of the ways that guests were able to sustain their feminine identities away from the resort. Discussing the importance of these snapshots of stolen time, Cummings wrote, “I dwelt so much in my memory and my daydreams that I desperately wanted some concrete souvenir of my rare moments of femininity.” Those souvenirs were also avidly shared, almost like trading cards, such that the photos became a kind of initiation into the international sorority of cross-dressers.

Back home, in repressive Cold War-era environments, their secret lives brought the threat of firings, imprisonment and potential violence. Given those consequences, the mere creation of these images—playful, tender and full of joy—was itself an act of resistance. “I believe these are ‘witness’ pictures,” Swope wrote, “reviewed over the years as a way of validating an identity, a part-time life that was perhaps more real than their lives away from Casa Susanna.”

Ultimately, for some of Casa Susanna’s denizens—including, eventually, Susanna herself—the slivers of time spent at her safe haven weren’t enough; and it was in part the resort that helped them come to that realization. Touring the property 60 years after her first visit, Cummings recalled thinking, “if I go to Casa Susanna and I find that I’m more woman inside than I am man, that might be the point where my new life starts.” For her part, Susanna announced the decision to live full time as a woman following “precious weeks” spent without Tito in the summer of 1969. “Constant swinging to and fro from him to her, back and forth, keeps you off balance. It is not restful,” she wrote in the October 1969 issue of Transvestia. “I realized the why of my increasing longing to live as Susanna more or less permanently. I am weary of this constant changing back and forth. I want peace within my own heart.”

We would like to thank the Art Gallery of Ontario for providing access to its extraordinary collection of images from Casa Susanna. To explore, visit the AGO's collection.

At American Experience we're always coming across photos from the past that we can't stop thinking about—images that are worth a thousand words.