Drawing the Political Lines of Apollo

By Neil M. Maher

In mid-July of 1969 more than one million Americans flocked to Cape Canaveral, Florida to witness the Apollo 11 launch. They made the pilgrimage not only to cheer on astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins, but also to celebrate the United States for beating the Soviet Union to the moon. Yet a mere three weeks later, in upstate New York, a very different type of gathering took place. A half million “hippies” at Woodstock grooved to music that was critical of the country, especially for its involvement in the Vietnam War.

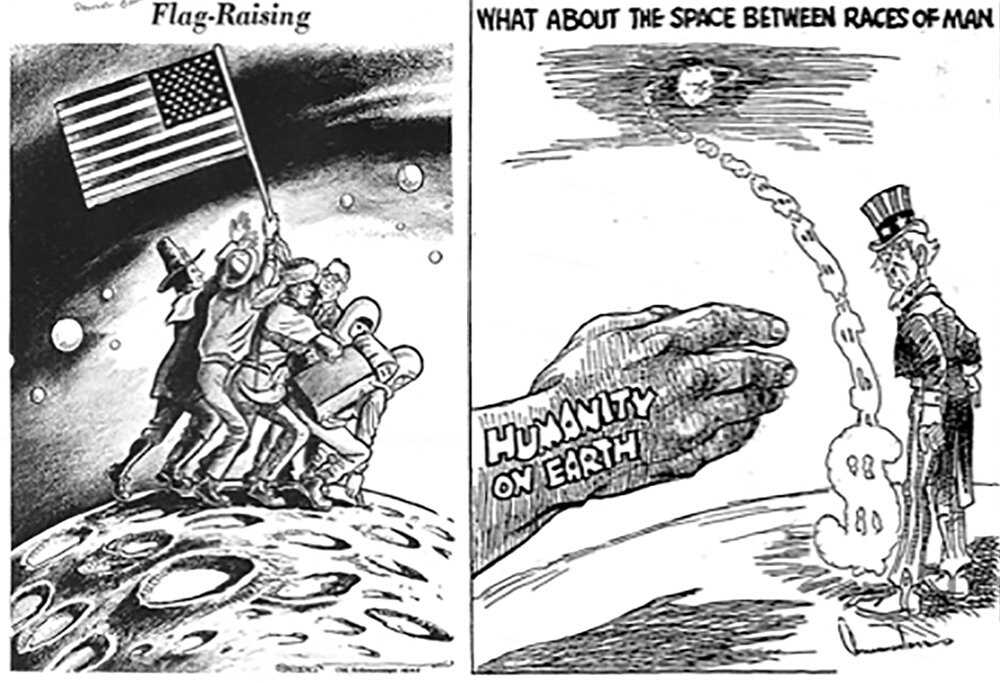

This cultural debate playing out during the summer of 1969 also appeared in political cartoons splashed across the nation’s newspapers. Those making the pilgrimage to the Cape would no doubt have appreciated “Flag-Raising,” which appeared in Alabama’s Birmingham News soon after the Apollo 11 moon landing. Drawn by conservative Southern cartoonist Charles Brooks, the illustration echoed the imagery of the famous World War II Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima photograph but set the scene on the lunar surface. Brooks replaced soldiers with a chronological who’s-who of pioneers from the old and new frontiers, including a pilgrim, coonskin-capped settler, California gold miner, and NASA administrator, all helping a pair of astronauts plant the American flag on a crater-pocked moon. The cartoon’s message was all too obvious – Apollo was the next step in our Manifest Destiny.

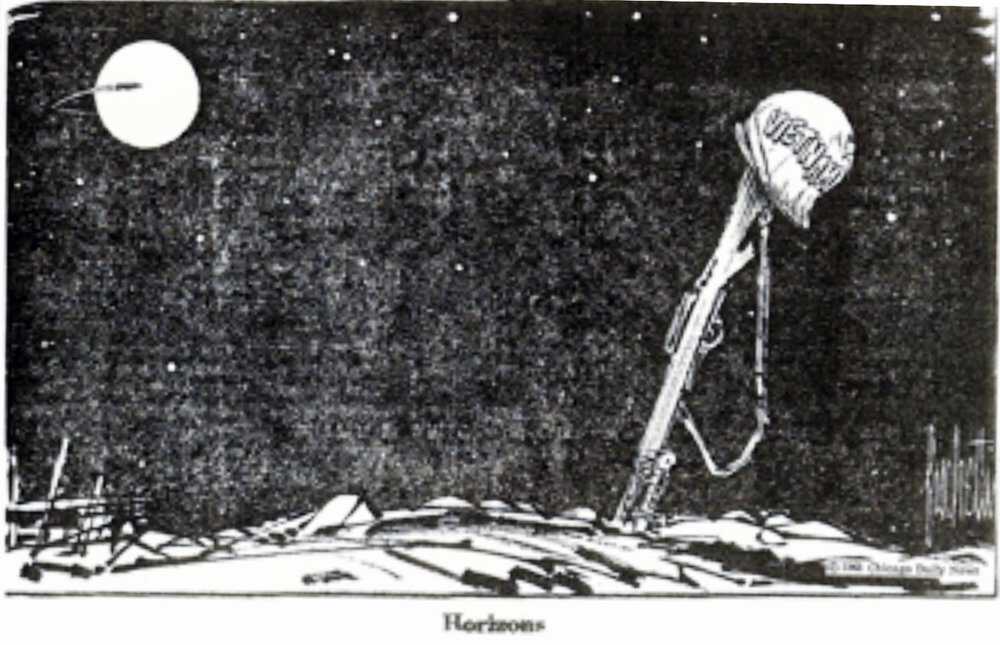

Woodstock’s hippies, along with others opposing the war in Vietnam, had a quite different take on the space race, and this, too, appeared prominently in the political cartoons of the era. The year before the Apollo 11 launch, for instance, the Chicago Daily News published an illustration by the Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist John Fischetti that contrasted the technological progress of America’s space program, symbolized by a small spaceship circling the moon, with the quagmire of the war, signified by a large gun planted firmly in Vietnam’s soil. Rather than celebrating space exploration by linking it to the nation’s former frontier, as Brooks did, Fischetti and those who enjoyed his cartoon instead criticized Apollo by associating it with what they believed to be American aggression in Southeast Asia.

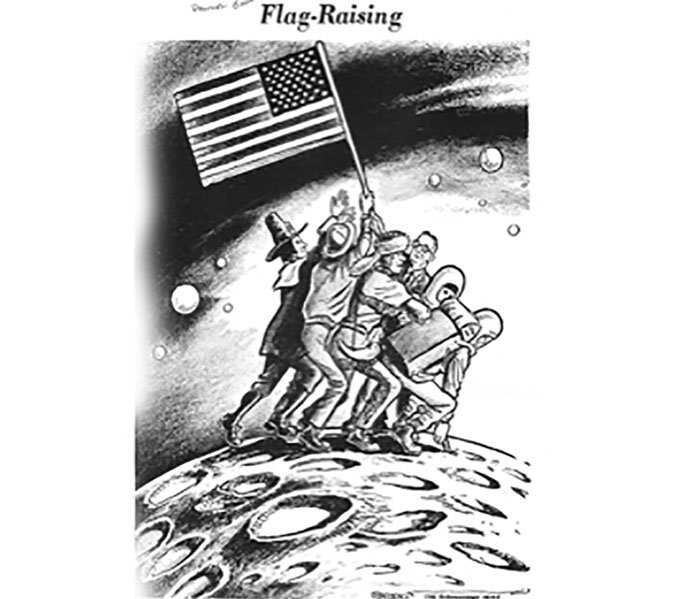

The Chicago Defender, a cornerstone of the black press at the time, illustrated African-American views in “What about the Space between Races of Man,” a cartoon by Chester Commodore, published on the eve of the Apollo 11 launch. In it, a black hand labeled “Humanity on Earth” reached out towards a stream of dollar sign-shaped exhaust emanating from a small Apollo spacecraft orbiting the moon in the distance. African American opposition to the space race was also suggested by the body language of the cartoon’s Uncle Sam, who protectively straddled the rising dollar signs while turning his face, in apparent annoyance, to the outstretched hand. During the late 1960s, the Chicago Defender ran nearly one dozen cartoons that similarly illustrated both the anger and apathy of African Americans regarding the moon landing.

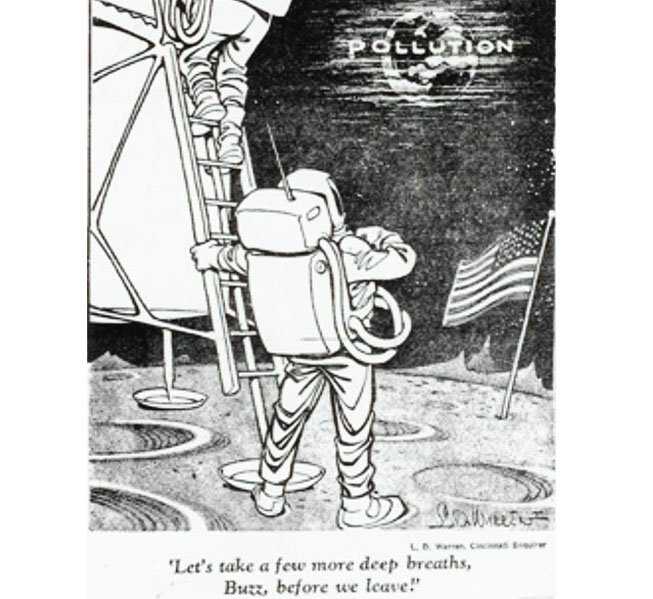

Environmentalists also had a bone to pick with Apollo. During the summer of 1969, one of the most poignant expressions was a cartoon by L.D. Warren that depicted Neil Armstrong pausing for a moment, before climbing back up the ladder for Apollo 11’s return trip, to stare back at a smog-shrouded Earth with the word “POLLUTION” obscuring most of North America. “Let’s take a few more deep breaths, Buzz, before we leave!” Armstrong tells Aldrin. The message, unlike the atmosphere back home, was crystal clear. In the rush to land men on the moon, the space race in general, and Apollo in particular, had diverted the nation’s attention form more pressing environmental problems on Earth.

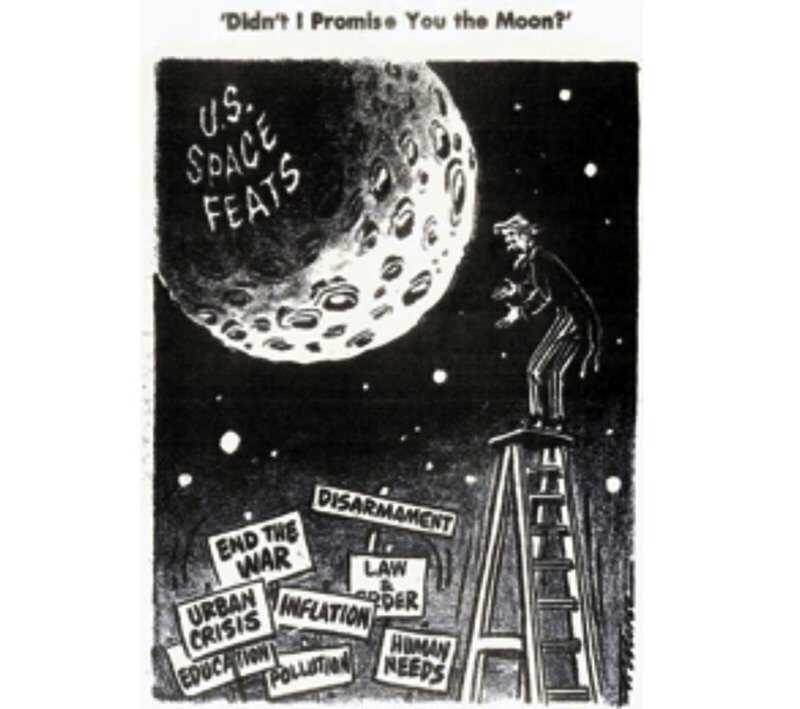

One final cartoon appearing two months before the Apollo 11 launch brings many of these political concerns together. Titled “Didn’t I Promise You the Moon?” the illustration by Franklin Morse, placed an obviously distraught Uncle Sam directly between the two competing camps in this national dispute. Up above his head floated a cratered moon with the words “U.S. Space Feats” written across its dark side, which symbolized the celebratory stance of those gathering at Cape Canaveral in mid-July of 1969. Below Uncle Sam’s ladder was a quite different scene, represented by a sea of protest signs reading, “END THE WAR,” “URBAN CRISIS” and “POLLUTION.” Taken together these placards illustrated a quite different national priority, one focused not on beating the Russians to the moon, but on “HUMAN NEEDS” back on Earth, as another protest sign explained.

Political cartoons appearing during the summer of 1969 illustrate a cultural divide over the state, and future direction, of the nation. Should America spend twenty billion dollars to win a Cold War battle to land the first humans on the moon? Or should the United States use those resources instead to tackle problems closer to home, including war, racism and environmental pollution? By suggesting various answers to these questions, political cartoons invited Americans into an important civic dialogue at a time of great social upheaval and political unrest.

Neil M. Maher is a history professor at the New Jersey Institute of Technology and Rutgers University at Newark, where he teaches environmental and political history. He has written about the Johnson Space Center’s beauty pageant in his most recent, award-winning book, Apollo in the Age of Aquarius (Harvard University Press, 2017).