Wernher von Braun’s Record on Civil Rights

On June 8, 1965, one of 20th century America’s most notorious racists was stopped in his tracks by a former Nazi preaching racial integration.

By Steven Moss and Richard Paul

In June 1965, Alabama governor George C. Wallace scheduled a tour of NASA’s Huntsville, Alabama test site, the Marshall Space Flight Center. The visit was part of a road trip he organized for small town newspaper editors, designed to show them “the real Alabama.” Wallace had come into office promising "segregation now, segregation tomorrow and segregation forever" and backed up that promise by standing in the doorway of the University of Alabama to personally block African-American students from enrolling. Unabashed by the shocking acts of anti-civil rights brutality and murder carried out with impunity during his first year in office, Wallace made a brief presidential run in 1964. A national political force and a viable potential presidential candidate for 1968, Wallace was now poised to take credit for Huntsville's part in getting a man on the moon. NASA turned to the flight center's director, Wernher von Braun, to shield it from being drawn into the governor's segregationist agenda. An unlikely emissary for Southern tolerance and moderation, von Braun was a former member of the Nazi SS and had used concentration camp inmates' slave labor to build Hitler’s V-2 rockets. But Von Braun threw himself into addressing the legacy of slavery in Alabama, and Wallace was going to learn just what he was up against.

Von Braun came to the US with a group of about 125 engineers, scientists and technicians, the last of whom were captured by American soldiers after the Germans moved from their test site at Peenemünde, near the Baltic Sea, to southern Germany as part of a final stand by the SS in the Alps mountains. US authorities wanted to keep the V-2s out of the hands of the Soviet Union. The US did not have the know-how to use the V-2s, so it brought the scientists to America—first to Boston, then to Ft. Bliss, Texas; and finally to a 30,000 acre enclave in Wallace’s state, in Huntsville, Alabama.

As Wallace's caravan made its way towards the Marshall Space Flight Center, von Braun was monitoring a push in the Alabama state legislature to create a George Wallace Space Museum in Huntsville. The visit was becoming a national story as the twenty-seven editors already with Wallace were joined by twenty-one reporters from national publications like Time and the New York Times as well as by most of the Alabama State Legislature. Days before the group’s arrival in Huntsville, Wallace lectured at length about the “Communist conspiracy” at the root of the civil rights movement.

In a conversation that von Braun captured with a secret recording system he had installed in his office, he told NASA Administrator James Webb that they needed to make it clear who was opposing Wallace—that it had to be “perfectly plain that this is not just NASA, but also the government.” Webb agreed and suggested von Braun call the commander of the Army base next door and tell him the Secretary of the Army was “in on the act.”

“Do you think the Secretary of the Army would come personally?” von Braun asked, trying to go Webb one better. But Webb didn’t think so. “He has to fight a war in Vietnam,” but Webb said the Secretary agreed with him that Wallace should not be allowed to “make a single move without meeting me head-on.” To that, von Braun joked that Wallace “may cancel his trip if he knows that you’ll meet him in the schoolhouse door.”

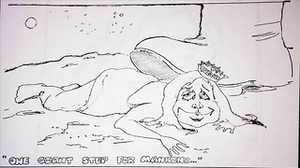

Webb and von Braun met Wallace with a full-on NASA extravaganza. Von Braun corralled the governor, the legislators and the press into a holding area and treated them to a rare and explosive show—a static firing of the Saturn V rocket’s first stage. This was just like an Apollo rocket launch with all the suspense, the countdown and all the noise, just without the launch itself. Afterwards, while everyone stayed in the visitors’ area “for safety reasons,” von Braun and Webb walked out and lectured their captive audience about race. Alabama needed to offer all the same opportunities as other states, von Braun remarked. “The era belongs to those who can shed the shackles of the past,” he said, which the New York Times took as a reference to slavery. Wallace never came back to Huntsville for the remainder of NASA’s mission to the Moon.

There are no easy conclusions about why a former Nazi became NASA’s point man on civil rights in Alabama. Von Braun's singular focus was rockets—and his history on racial issues in Alabama was uneven, at best, and arguably exemplified NASA’s broader conflicts on the issue.

President Lyndon Johnson saw a link between southern poverty and southern racism. If an activist federal government could solve one, Johnson believed, it could solve the other and transform the South. It was common knowledge in African American communities that Johnson intended to use the space program to end workplace discrimination, and Johnson was not shy about promoting the idea. Yet NASA trailed most federal agencies when it came to hiring African Americans.

Throughout the race to the Moon, NASA made gestures that challenged segregation’s most powerful leaders, often at the risk of severe cost to the agency and its mission. Just as often though, NASA shrank from opportunities to cope with segregation and even to carry out its responsibility to enforce policies against it.

In von Braun’s case, from the moment he got to Huntsville in 1949, he pushed for the city and the state to improve. He asked the legislature to build a research institute and a University of Alabama center in Huntsville. Over the next 20 years, von Braun and his team transformed the former Watercress Capital of the World into the intellectual and engineering center of the US space program. But NASA in the South was still in the South. African American NASA employees could do math and build circuits next to white people, but once they walked off the base, they could not use the same toilet as their coworkers or meet in the same hotels and restaurants. As NASA’s first African-American engineer, Morgan Watson put it, “Once you step out of Huntsville, you were in Alabama.”

In 1952, von Braun drove the 20 minutes to the all-black Alabama A&M College, to recruit a group of its science majors for a quixotic outreach campaign at a local white high school. One of the A&M students, Clyde Foster, was not really sure what von Braun’s aim was, but he guessed the scientist was looking to get a group of mostly farm kids interested in the wonders of outer space. Why von Braun thought black college students would be the best ambassadors to rural white children is lost to history. The result was that Foster and six other A&M students found themselves standing on stage in front of an auditorium filled with white kids who were known to throw trash and spit from their school bus windows at any blacks they passed.

Predictably, “nobody was listening,” Foster said, and the assembly was a disaster. Maybe von Braun’s astonishing lack of cultural sensitivity stemmed from his being so new and so out of place in the South. Ironically, the assembly had one positive result: it introduced Clyde Foster to the space program, which he subsequently joined in 1960. During his three decades at the Marshall Space Flight Center, Foster got more black workers jobs, advanced the education of more black engineering students and cleared the path toward equality more enduringly than any other African American NASA employee.

Ten years later, von Braun failed to support change during the turbulence of Huntsville’s lunch counter sit-ins. As a NASA manger, Von Braun was operating in a federal government that President John F. Kennedy sought to alter almost immediately after taking office. Early in 1961, Kennedy signed Executive Order 10925, which required the nation’s 38,000 federal contractors to hire without regard to race. NASA was based primarily in the South, and as its mission grew, so too did the importance of the executive order and the Equal Employment Opportunity Council it established. Wernher von Braun was the manager of a federal installation. It was his job to enforce the rules.

While local government reaction to the Huntsville sit-ins was nowhere near as ham-handed as elsewhere in the state, coverage in the black press shows that Huntsville was clearly “in Alabama.” While white businesses were driven to near collapse by black boycotts, dozens of blacks were jailed and a white NASA worker who ate lunch with black students was kidnapped, stripped naked, sprayed with a substance similar to pepper spray, and left on the side of a road.

Six months into the sit-ins, with pickets marching outside the Marshall Space Flight Center to draw the nation's attention to inequality and segregation in Huntsville, von Braun’s public affairs officer, Bart Slattery, told him Attorney General Robert Kennedy was “eager to visit” the city. Slattery was nervous the visit could generate “rumors that [Kennedy] might be looking into our employment practices.” In a memo to von Braun, Slattery related his efforts to find Kennedy an excuse to go anywhere else in Alabama. At the bottom of the memo, von Braun underlined Slattery’s name and wrote, “Let’s talk this over.” Robert Kennedy never did come to Huntsville during the sit-ins.

Though Robert Kennedy was kept from visiting, his impact was felt a few months later. As the spring 1963 protests in Birmingham came to a close, two bombings on the same night in May touched off a black uprising against chronic acts of racial terror by whites. African Americans fought back against the police with rocks, clubs and knives, injuring 24 people—and Kennedy got scared. When he learned at a meeting of the Council of Equal Employment Opportunity that only 15 African Americans worked for the federal government in Birmingham, he exploded. Without visible government action to address inequality, he feared there were only going to be more violent conflicts in other cities. Kennedy began twisting arms—starting with Lyndon Johnson, who, when he was Senate majority leader, was instrumental in the founding of NASA and selling it to the public. Johnson in turn twisted the arm of NASA Administrator Webb, and Webb twisted the arm of Wernher von Braun. Over the next six weeks, NASA engaged in its most significant and sustained action on civil rights in its history.

The Marshall Space Flight Center hired an African-American recruiter named Charlie Smoot. Before Smoot, NASA had only ever sent white recruiters to black colleges.

Smoot was able to assuage the fears of potential recruits, and he brought dozens of black engineers to NASA’s Southern installations. To help bring in the flight center's first African American engineering students, Von Braun also invited the presidents of thirteen black colleges to Marshall and expanded its co-op program to include a dozen black colleges.

Despite these significant moves, NASA still ranked at the bottom on equal employment compared to other federal agencies. After persistent claims by the Marshall Space Flight Center’s all-white human resources office that it lost the paperwork of black employees looking for promotions, two black workers made a formal complaint. Following a hearing officer’s “finding of discrimination,” von Braun wrote headquarters to complain that the officer had impugned his leadership staff. The officer made “gratuitous and unwarranted” statements suggesting his men were racists, von Braun said. He pointed to the efforts the flight center made earlier in the year and received an apologetic letter back from headquarters.

During the 1964 presidential campaign, James Webb threatened to move NASA out of Alabama. News that prisoners working at Peenemünde during the war had been starved and tortured had begun “to seep into the Western media,” according to von Braun biographer Michael Neufeld. Despite this, however, von Braun was sent out to make the case that if the Alabama business community wanted to maintain the integrity of the Huntsville credit market, then the racial status quo was going to have to end. No one had more influence in Huntsville than von Braun.

Von Braun spoke to Chambers of Commerce around Alabama, lecturing about “fair employment and improvement of racial relations.” And in a more symbolic move, he went to Miles College in Fairfield, Alabama for the opening of a new physics building. The historically black college was the intellectual nerve center for the black community during Birmingham’s racial unrest.

That black publications like Jet magazine and the Chicago Defender covered von Braun’s speech, is a measure of the black community’s favorable view of NASA’s intensified push for civil rights.

Von Braun's public conversion was now complete. His V-2 missiles which rained death on London gave birth to the Saturn V, which propelled men to the moon. Within 20 years he had evolved from potential war criminal and refugee to the savior of Huntsville and an American Cold War hero. In that same time he went from overseeing a program of forced labor to championing civil rights and racial integration in Alabama.

Von Braun had dreamed since childhood of building the rocket that would put a human on the moon. It did not matter to him whether his support came from the regime that was led by Hitler’s hatred or by the Great Society-era inclusiveness of Lyndon Johnson. Regardless of what else was happening in the world, von Braun turned with the prevailing winds to achieve his singular devotion.

Steven Moss is co-author of We Could Not Fail: The First African Americans in the Space Program and an associate professor at Texas State Technical College. His thesis "NASA and Racial Equality in the South, 1961-1968" was one of the first academic studies of civil rights and the US space program.

Richard Paul has produced and written numerous stories for PRI’s Studio 360 and NPR’s Morning Edition and is co-author of the bestselling book We Could Not Fail: the First African Americans in the Space Program. His radio documentaries include the “Out of This World” series on the first women and first African Americans in the space program, “Shakespeare In American Life” and the award winning “We Were On Duty,” about 9/11.

Published May 11, 2019.