The Boy Who Collected Comics

Without William Randolph Hearst's pantheon of early cartoonists, there would be no sitcoms, no Mickey Mouse, no Star Wars.

Once upon a time there was a lonely rich boy whose mother insisted on dragging him away from home to strange lands. Deprived of friends his own age and missing his father, the boy found solace in becoming a collector of all sorts of odds and ends, of coins and stamps, of beer steins and porcelain. These served as substitute friends. Among his particular favorites were cartoon books filled with images of mischievous brothers pulling pranks on their elders. Nurtured by his love of these cartoon books, the boy would one day become an impresario who helped launch an American art form.

The boy, of course, was William Randolph Hearst. In 1874, the eleven year old Hearst found himself in Germany, a trip inspired by his mother Phoebe Hearst’s desire to civilize her son. In a letter home, she wrote that he had caught the collecting bug. “He wants all sorts of things,” she noted and has a “mania for antiquities, poor old boy.” The young Hearst would never cease to be a collector, and would one day fill a California castle with the treasures of the old world.

But he loved not just the elegant elite art which he crammed into San Simeon but also the more vulgar pleasures of popular culture. The cartoon book he particularly cherished was Max und Moritz by Wilhelm Busch, which featured the tales of practical jokes pulled by hellion siblings. Among other jakes, Max and Moritz poured gunpowder into the pipe of their teacher and filled up the bed of their sleeping uncle with May bugs. Hearst surely felt an affinity for these two brats since he himself was a notorious prankster: at Harvard he shocked the Boston Brahmins by keeping a pet alligator named Charlie and by sending his professors chamber pots as Christmas presents.

These escapades surely contributed to Heart’s expulsion from Harvard, an exile he welcomed since it allowed him to jump into the career he really wanted—as a newspaper man. His father owned a sleepy and ailing paper called the The San Francisco Examiner. In 1887, Hearst elbowed his way into running the paper and decided to revitalize it.

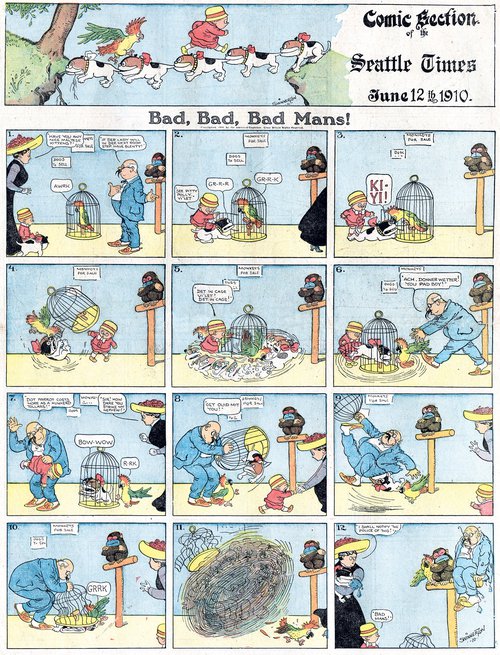

As a young man who still loved cartoons, Hearst instinctively knew that images were crucial for selling newspapers. One of his first big hires was Thomas Nast, the most famous and influential of American cartoonists, already a legend for drawings that turned the tide of public opinion against the grifters of Tammany Hall. Hearst used Nast, who had gone into semi-retirement, to go after West Coast politicians. A more daring hire was the 17 year old Jimmy Swinnerton, who proved to have a gift for drawing winning anthropomorphic animals. An 1893 promotional campaign had Examiner reporters go searching for live grizzly bears, an animal feared to be extinct. Swinnerton illustrated these reports with ever cuter cartoon bears, which became a marketing sensation that drove up circulation. Hearst took note of this fact and realized that cartoons could be the way he could achieve his next goal, capturing the New York market.

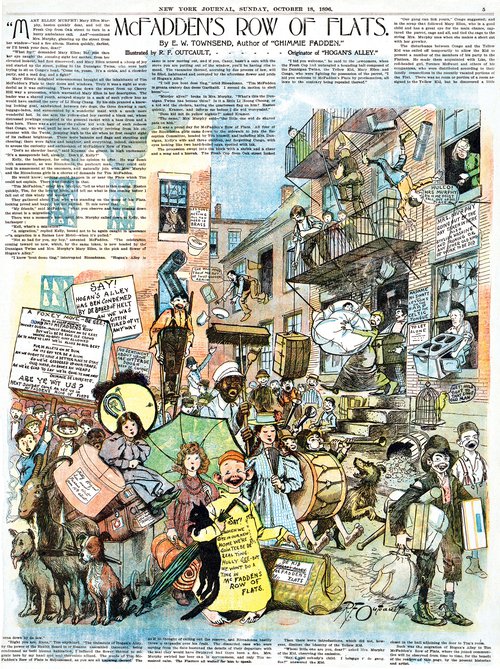

Hearst wasn’t the only father of the newspaper comics. The early 19th century newspapers were walls of grey text, enlivened only rarely by crude woodcuts that were often used just as placeholders. But by the late nineteenth, improvements in technology were making it increasingly possible to integrate highly textured drawings, sometimes in color, into daily newspapers. Joseph Pulitzer, owner of the New York World was the leader of the pack in transforming newspapers into a visual medium. In 1895, Pulitzer scored a big hit with The Yellow Kid (created by cartoonist Richard Outcault). A bald-headed Irish-American tenement dweller, the Yellow Kid earned his nickname from his lemon colored smock, which carried on it snarky comments about the inequality of the Gilded Age. A rambunctious portrait of slum life, The Yellow Kid was an early example of how the new form of newspaper comics could be a vehicle for social commentary as well as a mirror of contemporary mores.

As a publisher, Hearst retained the habits of a collector. Just as when he was a boy he would buy cartoon books, so as a man he would buy cartoonists (and reporters and editors). He hired Outcault to draw the Yellow Kid for The New York Journal. This launched a series of lawsuits that helped define intellectual property rights in the new age where cartoon imagery could be as profitable as the silver mines that Hearst’s father dug to create the family’s original fortune.

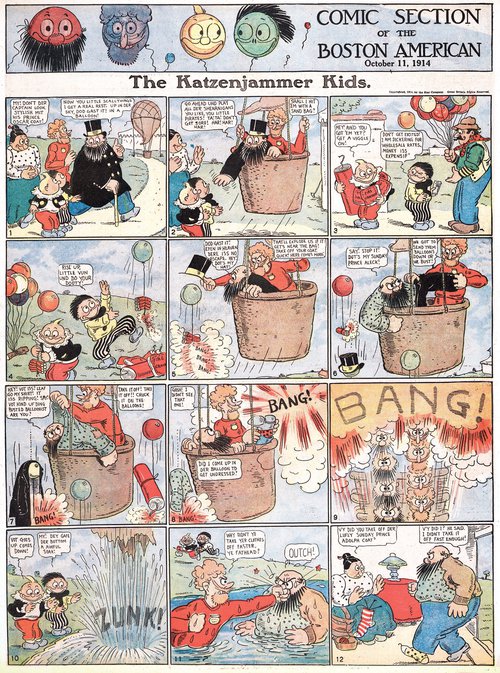

Hearst’s next big hit was also a kind of poaching: he worked with Rudolph Dirks to create The Katzenjammer Kids, a very close knock-off of Max and Moritz. In those early days, Hearst stylized himself as a radical populist eager to thumb his nose at the powers that be. That anarchic sensibility certainly played itself out in the misdeeds of the Katzenjammer Kids, who were quick to use any prop at hand, even a stick of dynamite, to overturn the adult order.

As an exasperated adult complains, “mit dose kids, society is nix!” The rebelliousness of the Katzenjammer Kids anticipated and influenced everything from Bugs Bunny to The Simpsons.

The early Hearst strips all had that rebel spirit. They often featured working class and immigrant characters: Frederick Opper’s Happy Hooligan (an Irish-American hobo), Maggie and Jiggs in George McManus’ Bringing Up Father (Irish immigrants made rich but uncomfortable in their nouveau riche haunts), Mutt and Jeff (Bud Fisher’s roughneck comedy about two reprobate gamblers) and Cliff Sterrett’s Poly and Her Pals (about a liberated young woman whose free and easy dating life shocks her parents). A more subtle form of subversion could be found in George Herriman’s Krazy Kat. Herriman was a light-skinned African-American who passed as white. His comic strip was about the ill-fated love a black cat has for a white mouse served, at least for Herriman if not most readers, as a wry condemnation of white supremacy).

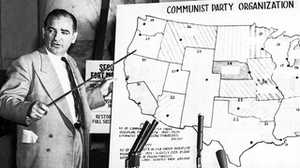

The evolution of the strips mirrored Hearst’s own changing worldview. By the 1920s, his earlier egalitarian populism, under the pressure of his mounting financial trouble and desire for lower taxes, had soured into a more reactionary form. Eventually he turned against the New Deal and warned of the danger of the Yellow Peril and the Red Peril. The later strips were more militaristic and nationalist, often featuring Asian and/or communist villains trying to destroy WASP-y American heroes. The story became blond Flash Gordon versus the Asiatic Ming the Merciless or Steve Canyon battling the communist hordes of China. In the humor strips, suburban comedy of marital mishaps, as in Blondie, replaced bomb throwing kids. The comic strips went from urban to suburban, from seditious to sedate.

It’s hard to overstate the impact of Hearst’s amazing pantheon of cartoonists, who enjoyed not just world-wide popularity but shaped many other creators. Without Bringing Up Father and Blondie, there would be no sitcoms. Without Krazy Kat, there would be no Mickey Mouse or Donald Duck. Without Flash Gordon, there would be no Star Wars.

To the very end, Hearst retained his brilliant eye for cartooning. His modus operandi remained that of the collector and poacher. He would read the newspapers of his rivals and scoop out the best talent with lavish offers. That’s how he ended up hiring Bud Fisher, Hal Foster, Roy Crane and Milton Caniff, among others. He remained the little boy who collected comics.

The Yellow Kid, created in 1895 by Richard Outcault (1863-1928)

Originally appearing in Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, The Yellow Kid created a sensation and is, if not the first comic strip, the comic strip that first popularized the form. Set in the slums of New York and featuring a multi-ethnic cast of poor kids who mimicked and mocked New York high society, the strip mirrored the inequality of the progressive era. Hearst poached Outcault and The Yellow Kid, which led to endless lawsuits.

Katzenjammer Kids, created in 1897 by Rudolph Dirks (1877-1968)

Deliberately imitative of Hearst’s childhood favorite, Max Und Moritz by Wilhelm Busch, the Katzenjammers were the bad boys of American comics, reflecting the anarchic energy of the tabloid press. Like the Yellow Kid, it would inspire lawsuits as Dirks was hired by rivals and created a copy-cat of his own creation.

Bad, Bad, Bad Mans! created in 1904 by Jimmy Swinnerton (1875-1974)

Swimmerton was Hearst’s closest friend among the cartoonists. His Little Jimmy was a slightly gentler version of the Katzenjammer Kids. Jimmy spread chaos, but by accident, not out of malice. Like George Herriman and Hearst, Swimmerton was an enthusiast for the American west of Monument Valley in Arizona, where he early moved to in 1906 as a cure for tuberculosis.

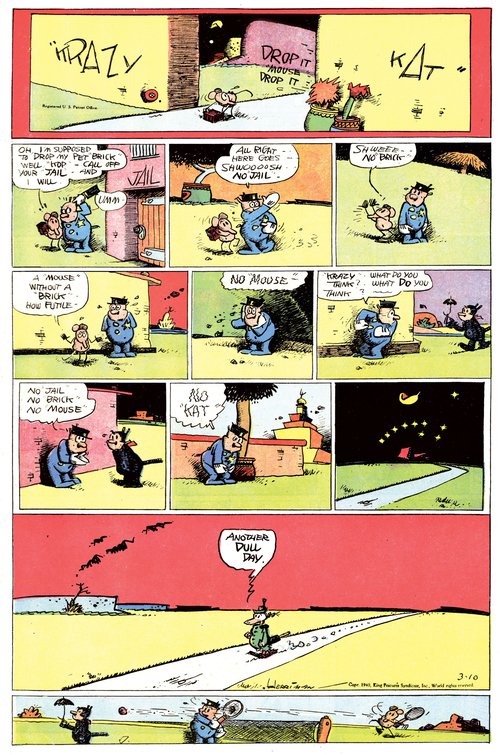

Krazy Kat, created in 1911 and launched as a strip in 1913 by George Herriman (1880-1944)

The greatest of all American comic strips, the poetic and modernist Krazy Kat used funny animals to create an enduring allegory about love, creativity, and identity. The Herrimans were a distinguished creole family in New Orleans in the 19th century, leaders in the African American community. As Jim Crow tightened its grip on the South, they moved to California where they passed as white. Herriman’s work often featured coded critiques of American racism.

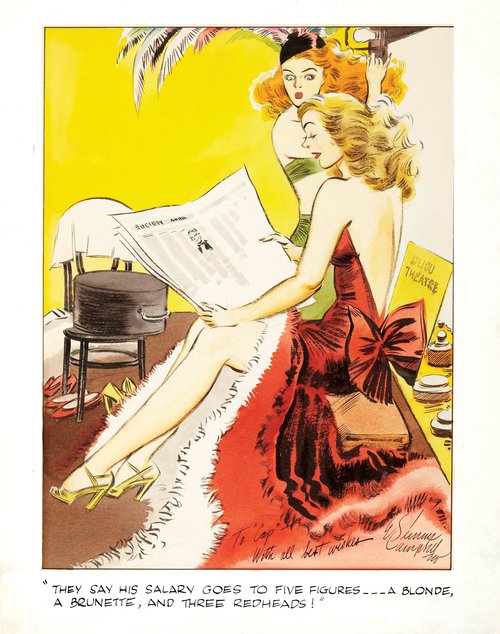

Cuties created in 1940 by E. Simms Campbell (1906-1971)

Hearst loved running cheesecake comics featuring beautiful women. One of the outstanding artists in the genre was Campbell, who in 1940 became the first openly Black cartoonist to work for a national newspaper syndicate (as compared to Herriman who passed as white). His work was distinguished by lovely linework.

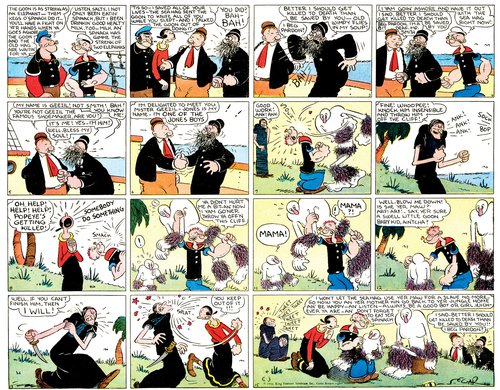

Popeye, created in 1929 in Thimble Theatre, as a strip started in 1919 by E.C. Segar (1894-1938)

A masterpiece of roughneck comedy, Segar’s Thimble Theatre tracked a group of lowlife hustlers like Olive Oyl and Ham Gravy. In 1929, Segar hit paydirt with the creation of Popeye, a gruff but kind-hearted sailor. With his two-fisted gallantry, Popeye became a popular hit. His adventures were enriched by a wonderful cast that included standbys like Olive Oyl and Ham Gravy but also J. Wellington Wimpy and the Sea Hag.

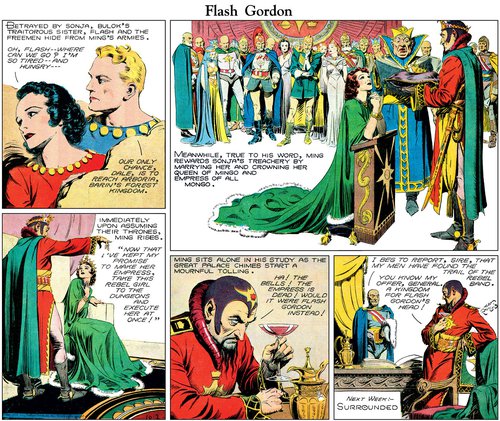

Flash Gordon, created in 1934 by Alex Raymond (1909-1956)

The 1930s saw the funnies shift to action and adventure. Flash Gordon, a space-opera featuring an earthman fighting Ming the Merciless, lead the way with exciting tales of space travel, monsters, and torturing villains. Raymond’s mastery of illustration set new standards and influenced the emerging genre of superhero comics.

Jeet Heer is a columnist for The Nation who also publishes the newsletter Time of Monsters. He is the author of two books: In Love With Art: Francoise Mouly’s Adventures in Comics with Art Spiegelman (Coach House Books) and Sweet Lechery: Essays, Profiles and Reviews (Porcupine’s Quill). With the cartoonists Chris Ware and Chris Oliveros, he has co-edited the Walt and Skeezix series which reprints Frank King's Gasoline Alley comic strip.

The comics in this article were provided courtesy of Dean Mullaney, author of King of the Comics: One Hundred Years of King Features Syndicate and creative director of the Library of American Comics.