How a Public Media Campaign Led to Japanese Incarceration during WWII

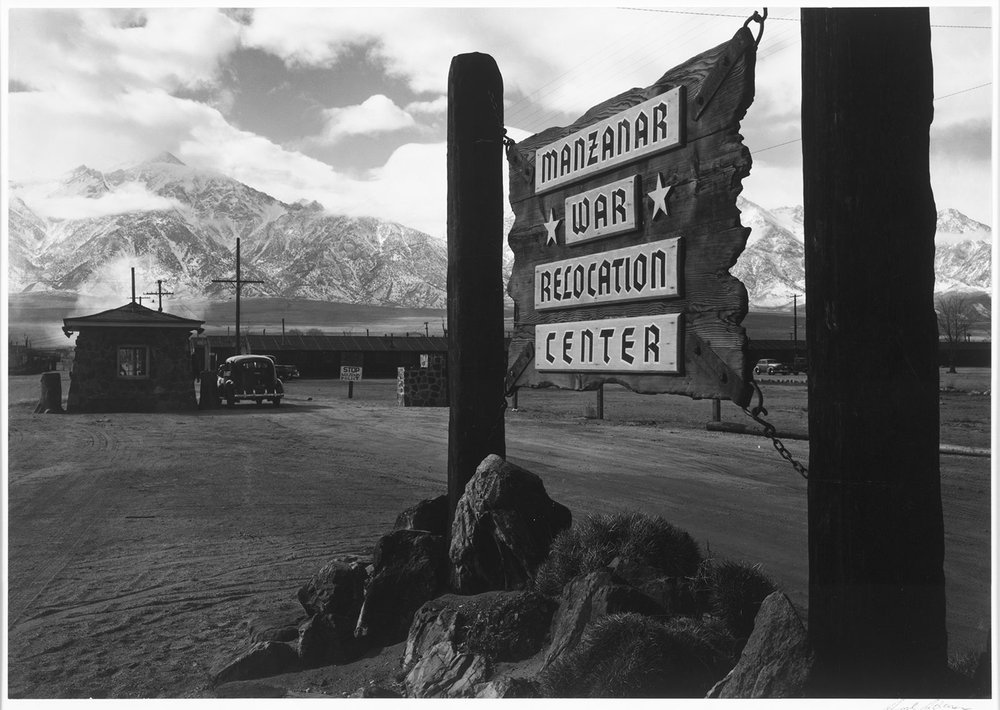

Images by photographers Dorothea Lange and Ansel Adams document this shameful moment in America’s history.

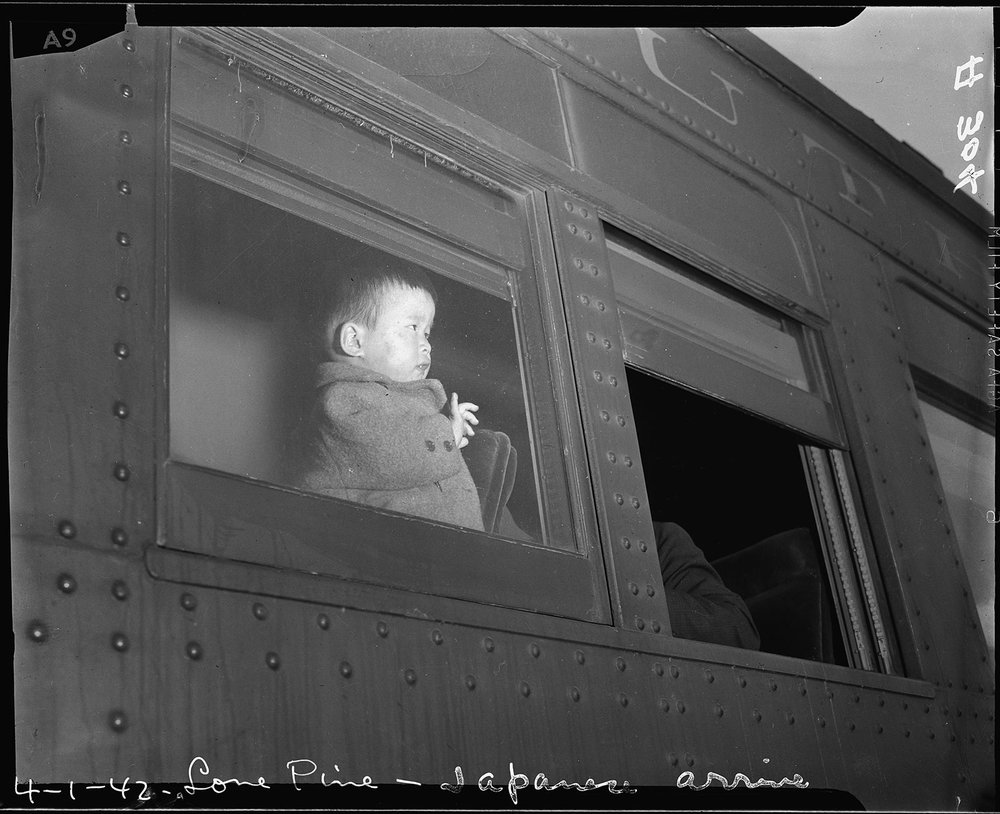

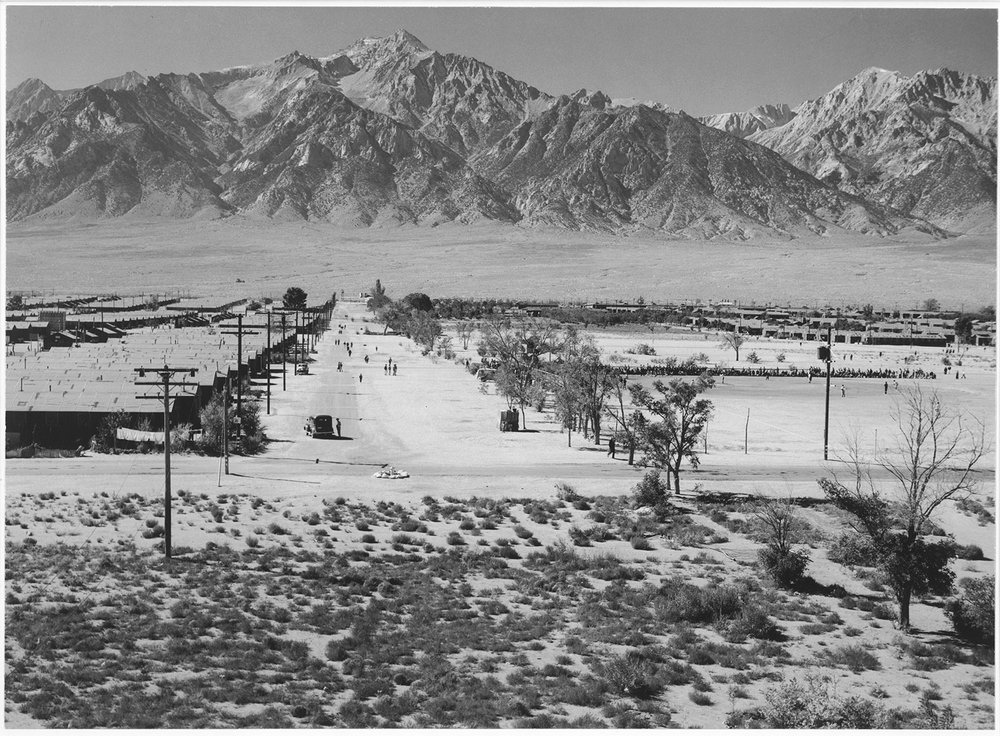

During World War II, over 120,000 persons of Japanese descent, two-thirds of whom were American citizens, were uprooted from their homes and banished for the duration of the war under guard and behind barbed wire. It was an act without precedent in the United States.

While the military attack of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese on December 7, 1941 was a surprise, the lash of public opinion and violent anti-Japanese outrage was not. The dominant, white majority’s pervasive distrust and racial intolerance of Japanese Americans had its origins in the history of California and the West and had been institutionalized in local ordinance and state law for decades. Asian immigrants were forbidden to attend white schools, live in white neighborhoods or intermarry.

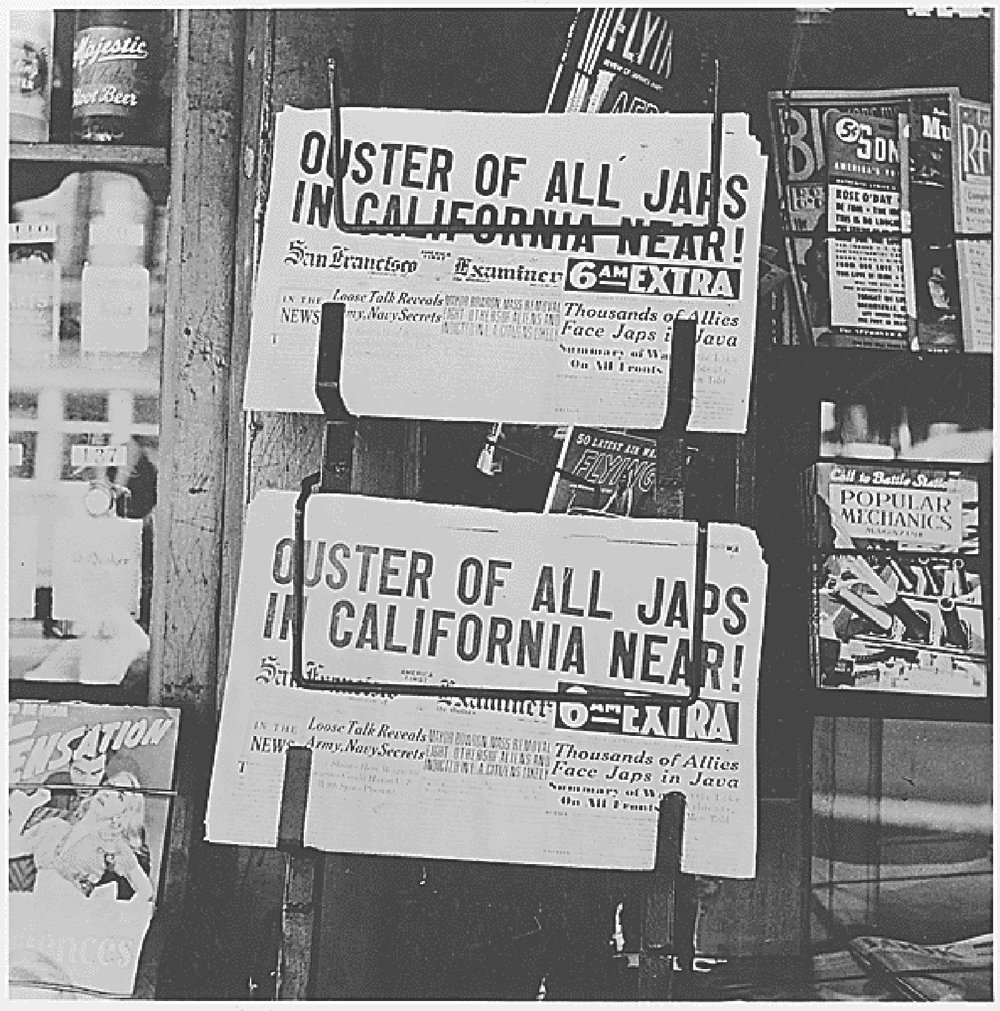

William Randolph Hearst’s newspapers were among the most influential newspapers in the country and had taken a stand against Japanese immigration starting in the early 1900s. Early Hearst paper headlines and editorials about the Japanese were largely hostile and included racial slurs such as “yellow,” “Mongolian” and the contraction “Jap.” Anti-Japanese opinion was only exacerbated with the popularization of the idea of the “Yellow Peril,” which conveyed American fears of a torrent of Asians spreading over the country and competing with whites for jobs. By the turn of the 20th century, military victories in the Russo-Japanese War inspired Hearst editorials depicting the Japanese as greedy and insatiable, as well as secretive and treacherous—with a penchant for spying.

That spectre of the “Yellow Peril” was revived more stridently following the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Negative public opinion of the Japanese, before and after the U.S. entered World War II, had been cultivated in the media. The resulting climate of anti-Japanese hostility and hysteria in turn fostered acceptance of the concentration camps.

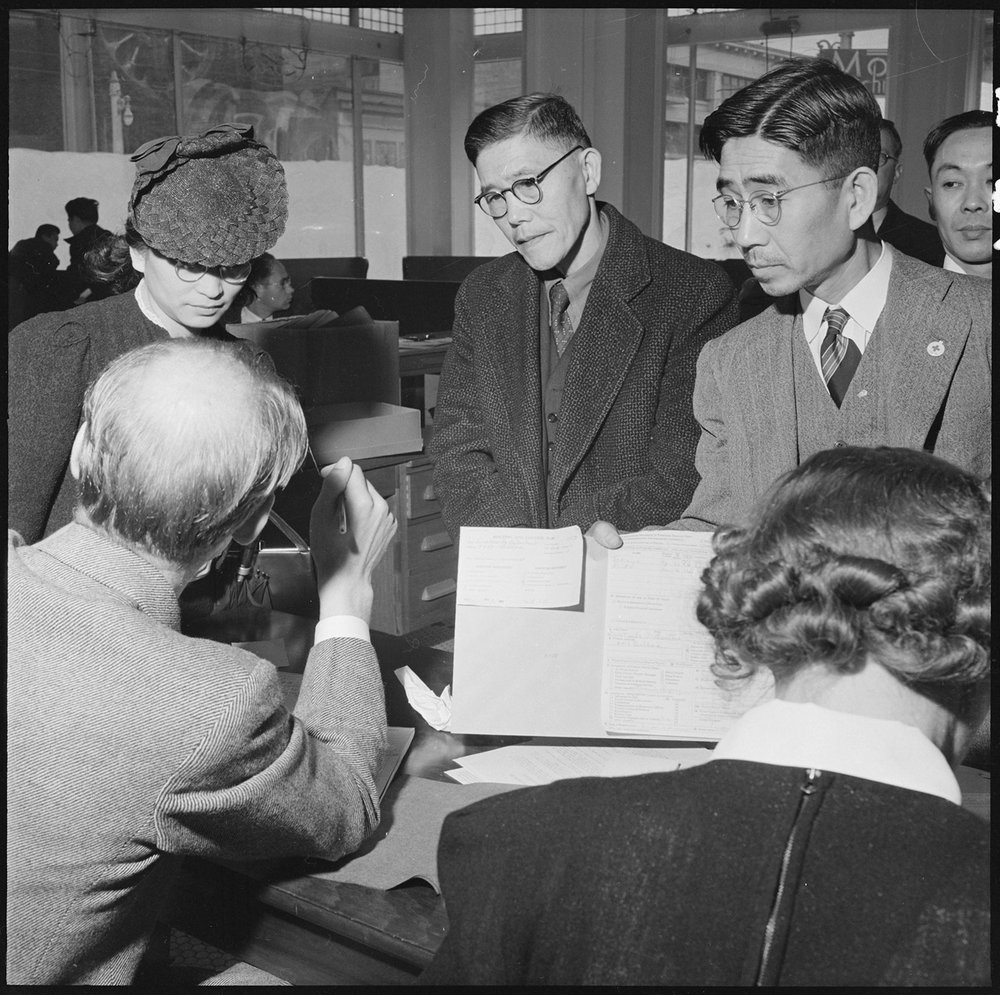

In the early days of the war, all enemy aliens (persons of Italian, German and Japanese ancestry who were not American citizens) were treated with suspicion and subject to raids, arrests, curfews and bank freezes. Newspaper articles reported on arrests and interrogations of purportedly suspicious people from all three countries. Throughout the months of January and February 1942, fear and humiliation in the face of the losses suffered at Pearl Harbor, along with reports of American battlefield deaths at the hands of Imperial Japan, Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, fueled increasingly inflammatory newspaper accounts and editorials throughout the United States. But there was a marked change of attitude, with hostilities directed specifically towards the Japanese, that can be traced over the weeks between December 1941 and March 1942. The U.S. government claimed that the possibility of sabotage, espionage and fifth-column activity made the removal of Japanese Americans a military necessity—an explanation that was widely accepted at the time but has since eroded under critical scrutiny.

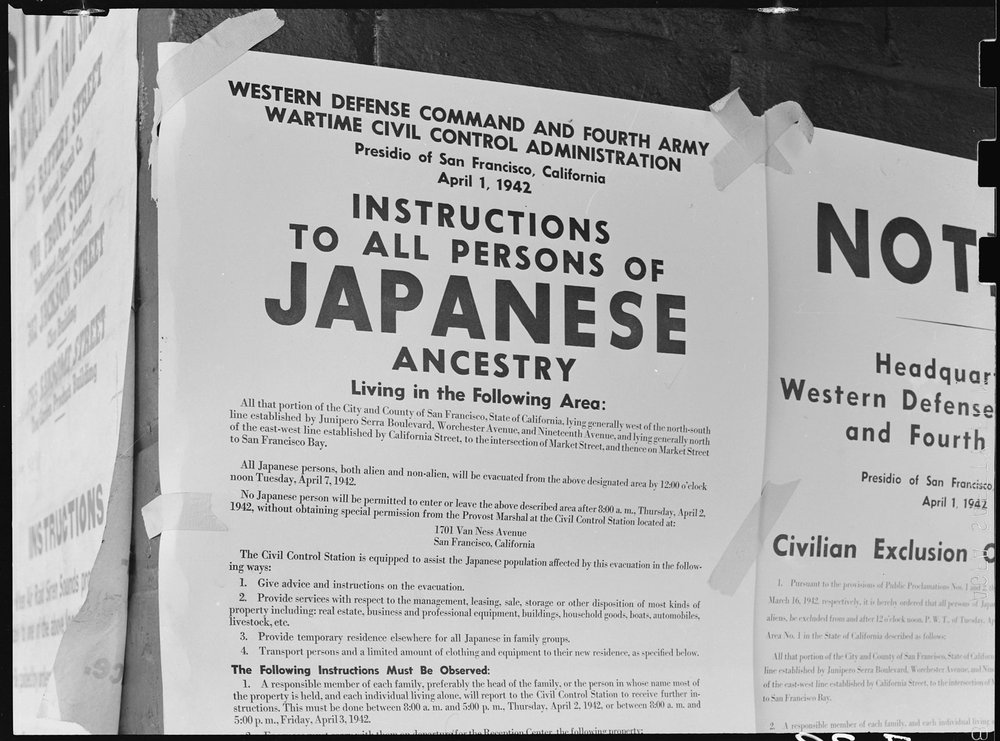

The increase in Hearst newspapers’ anti-Japanese stories, editorial columns, political cartoons and letters to the editor helped cultivate vicious hatred of the Japanese, but the plan to remove and confine the entire population of West Coast Japanese Americans was ultimately a political act. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, authorizing what was to become the mass forced removal and incarceration of all Japanese Americans on the West Coast. The order authorized the Secretary of War and any military commander designated by him “to prescribe military areas…from which any or all persons may be excluded,” although Japanese Americans are never specifically mentioned in the order.

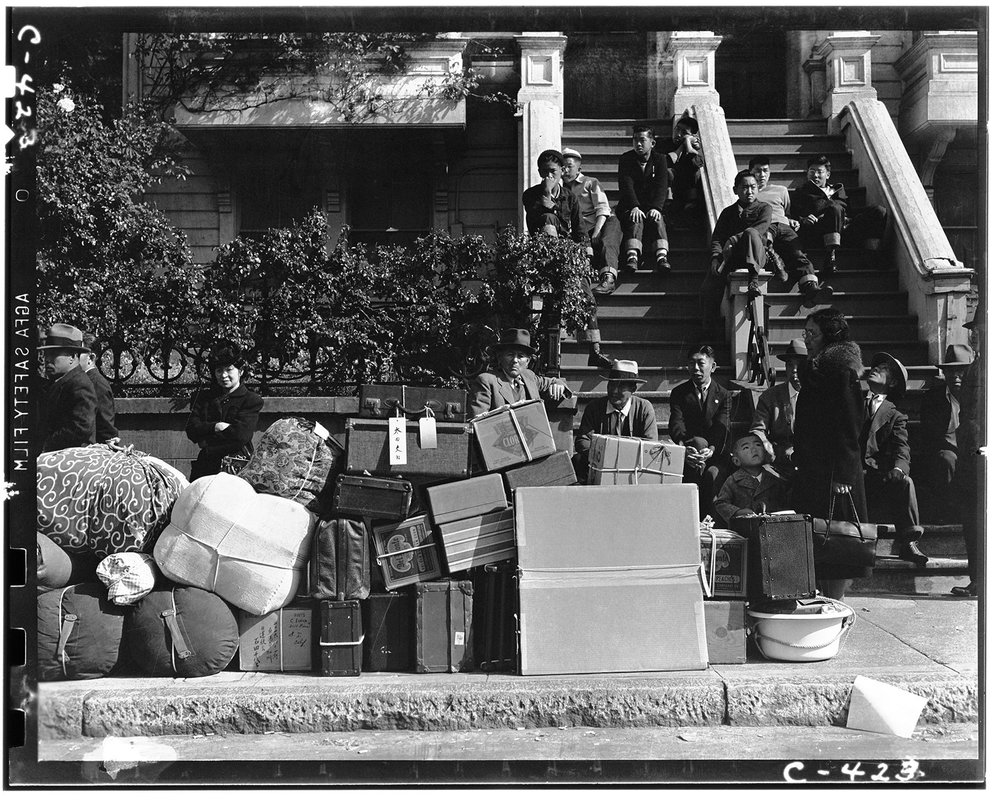

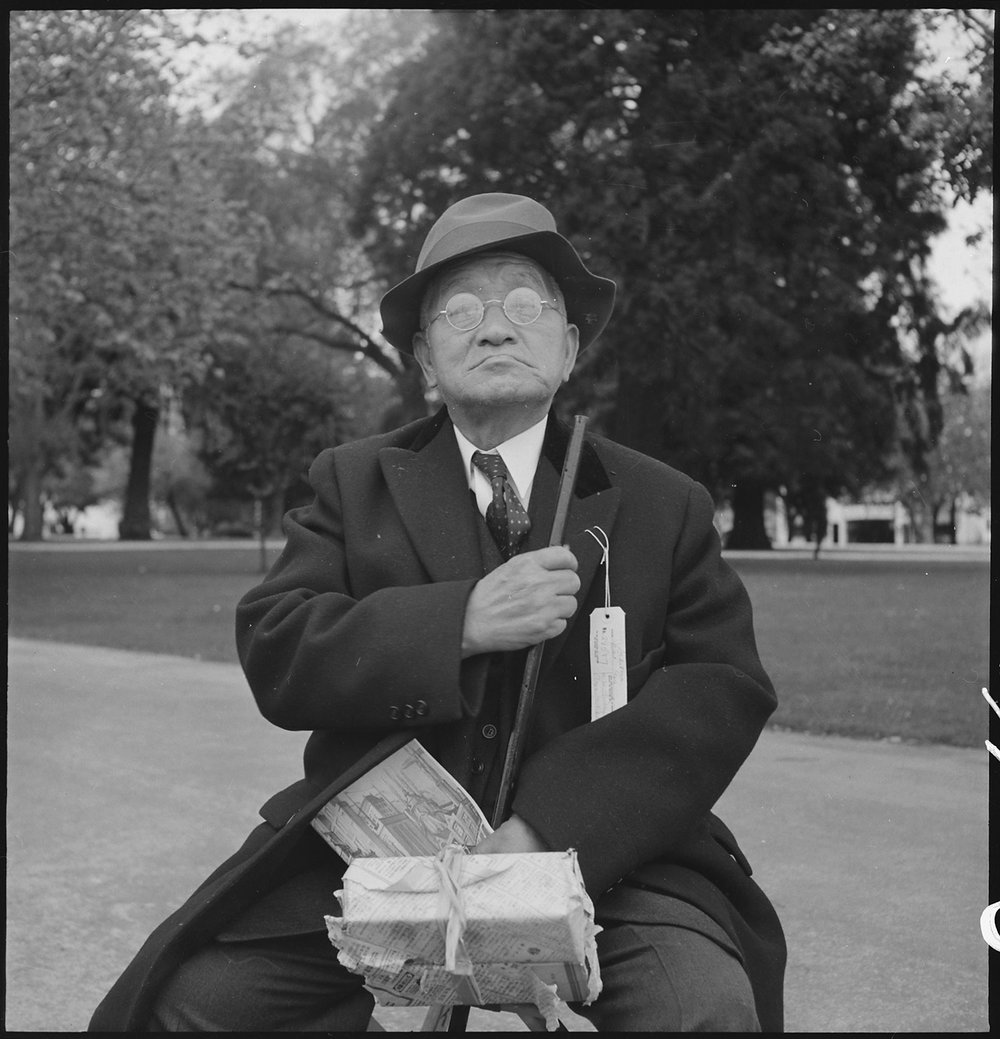

Overnight, EO 9066 reduced individual and family names to numbers on tags. The Army explicitly ordered the Japanese to assemble voluntarily for mass evacuation on a given date and time, with no more than what could be carried by hand. Read on for remembrances by Japanese Americans of their traumatic forced removal, juxtaposed with excerpts from Hearst newspapers and images of the tumultuous events that shook Japanese American communities from December 7, 1941 to late spring 1942.

When the Japanese sunk as low as they did on Sunday morning they were closer to unreasoning animals than human beings… No longer will men condemn the actions of others by saying it was a “skunkish trick.” Much more damning will be the phrase “Of all the lowest Japanesish things to do.”

- "Lowest Animals Now Surpassed," San Francisco Examiner, December 11, 1941

Machinery for eventual exclusion of all enemy aliens and all persons of Japanese ancestry from huge “strategic areas” of four western states was set up by military authorities yesterday...embracing all of California, Oregon, Washington and Arizona. ...Evacuation of German and Italian aliens will probably not start, the general indicated, until the Japanese have been removed. German and Italian aliens more than 70 years of age will probably not be required to move unless individually suspected.

- "Coastal Areas to Be Cleared of All Japs," San Francisco Examiner, March 4, 1942

Every day there was something else about other people being taken by the FBI. Then gradually we just couldn't believe the newspapers and what people were saying. And then there was talk about sending us away, and we just couldn't believe that they would do such a thing. It would be a situation where the whole community would be uprooted. But soon enough we were reading reports of other communities being evacuated from San Pedro and from Puget Sound. After a while we became aware that maybe things weren't going to just stop but would continue to get worse and worse.

- Mary Tsukamoto (And Justice for All)

Herd 'em up, pack 'em off and give 'em the inside room in the badlands. Let 'em be pinched, hurt, hungry, and dead up against it... Let us have no patience with the enemy or with anyone whose vein carry his blood… Let’s quit worrying about hurting the enemy’s feelings and start doing it.

- "Why We Treat the Japanese Well," The San Francisco Examiner, January 29, 1942

The evacuees are instructed to take with them sufficient blankets, bed linen and towels, toilet articles, soap and mirrors, adequate clothing, utensils including knives, forks, spoons, plates, bowls and cups, and any other small incidental property which can be carried easily.

- "Evacuation of 5,000 S.F. Japs Starts Today," San Francisco Examiner, April 6, 1942

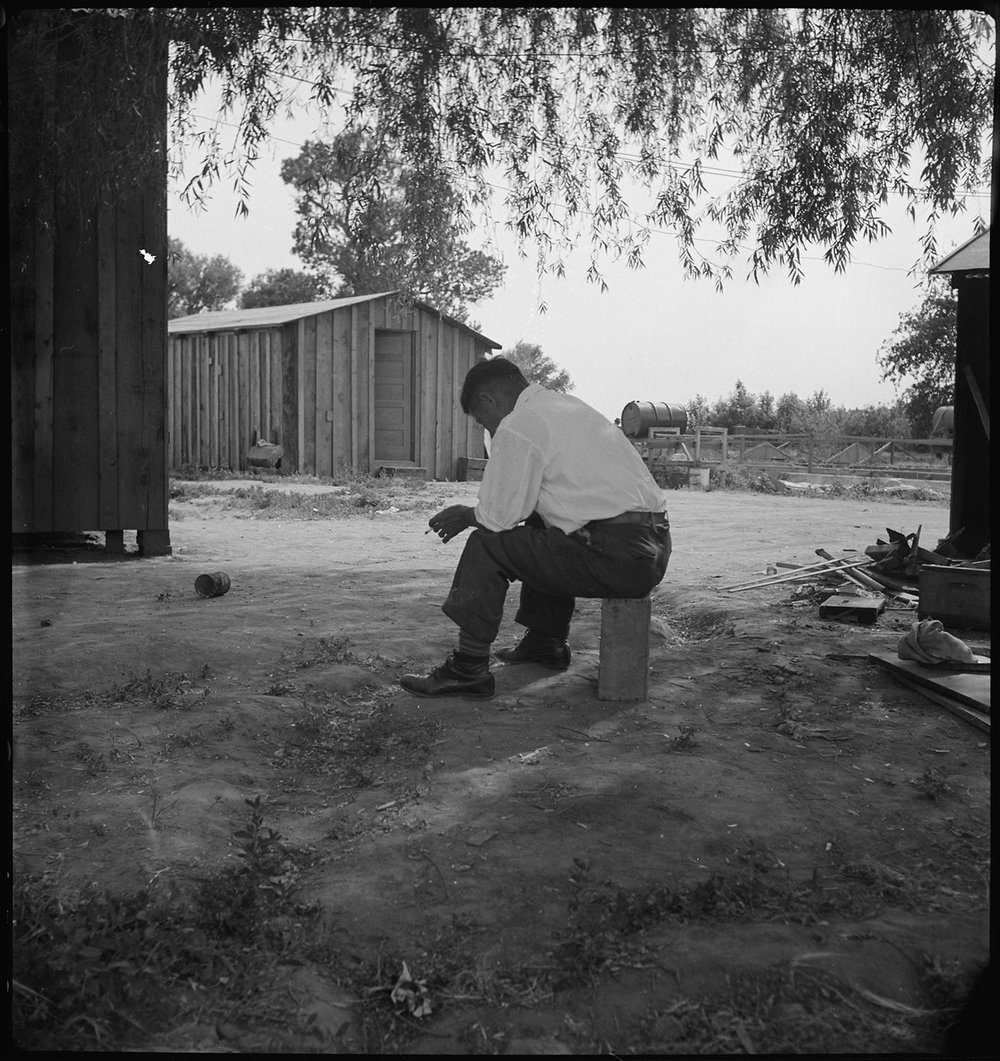

You hurt. You give up everything that you worked for that far, and I think everybody was at the point of just having gotten out of the Depression and was just getting on his feet. And then all that happens! You have to throw everything away. You feel you were betrayed.

- Yuri Tateishi (And Justice for All)

Two-thirds of the Japanese-Americans are dual citizens. Approximately 15,000 Japanese Americans on the Pacific Coast are citizens sent by their parents to Japan to be educated. Until these doubtful American citizens, and all other Japanese, are taken into protective custody the Pacific defense will not be complete.

- Seattle Post-Intelligencer, February 19, 1942

Suddenly the whole world turned dark. We started to speak in whispers... [W]e immediately sensed something terrible was going to happen. We just prayed that it wouldn't, but we sensed the things would be very difficult...[W]e knew that we needed to be prepared for the worst.

- Mary Tsukamoto (And Justice for All)

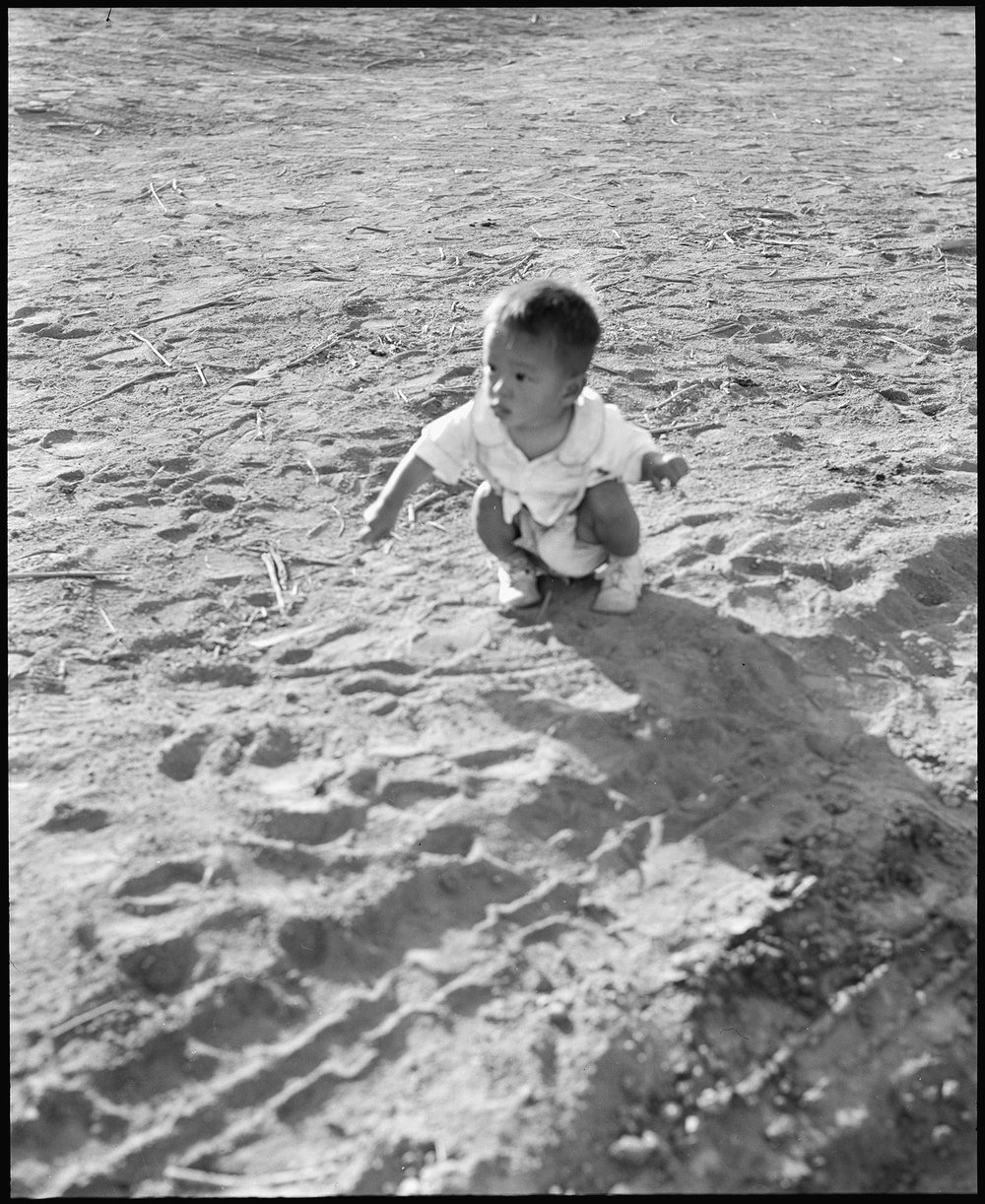

I vividly remember wartime propaganda posters and newsreel accounts about the ‘sneaky, treacherous, rapacious, yellow-bellied Japs’ who were the enemy. Nobody in the Government made a distinction between the “Japs” of the Japanese Imperial Army and me. I was one of the enemy, though 10 years old, and placed in a concentration camp.

- Robert Moteki, Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians testimony, November 23, 1981

I couldn't believe that American citizens were being uprooted, especially since my children were so young. I was just unable to answer the question myself as to why such a thing was being done to us. This kept hounding us over and over. Why? What necessity? It just didn't make sense.

- Violet de Cristoforo (And Justice for All)

You can’t tell a man’s loyalty by looking at him and there isn’t time now that we are at war to check on every individual. So why take a chance? The Japanese and the Japanese Americans should be taken into protective custody not only for the good of the United States but for their own welfare as well.

- Seattle Post-Intelligencer, February 19, 1942

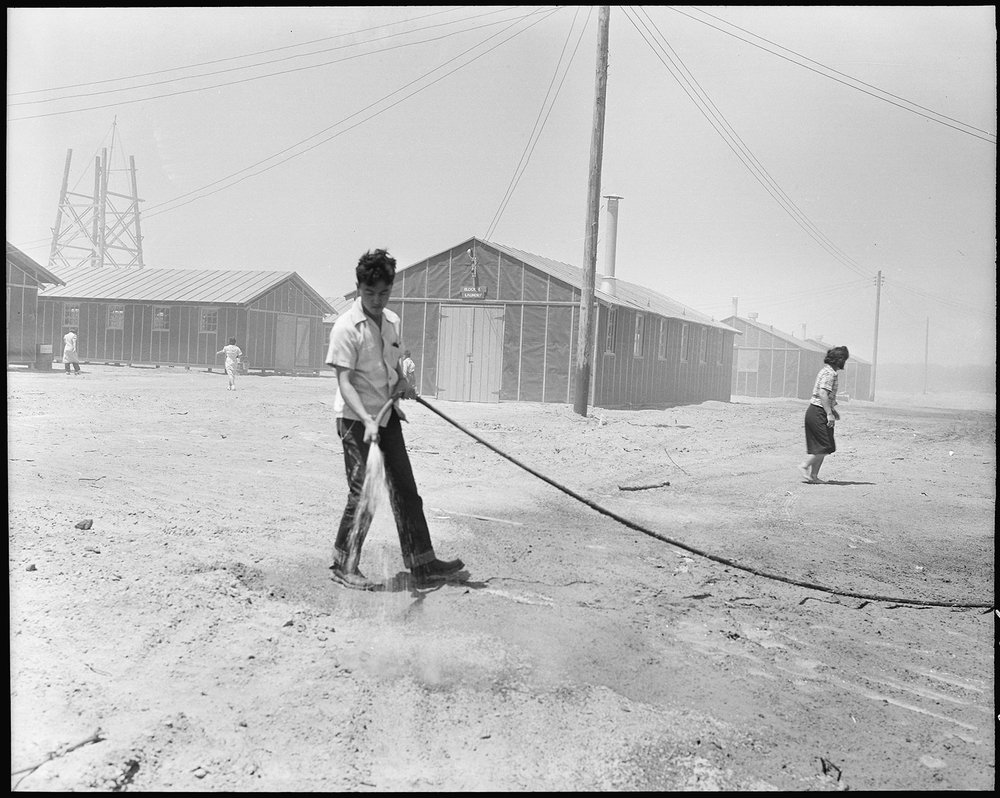

Ye Gods, it's a terrible place here. The dust storms are awful—can't see ahead of you, the rooms are dusty and even closed windows can't keep out the dust. We eat, sleep and live in the dust. Golly, how I miss California. I thought our stables in Tanforan [a race track used as a temporary assembly facility] were bad but it'd be heaven if we could only go back. People about me are discouraged and disappointed—they say it's no place for humans to live.

- Riyoko Kushida, Letter to Hideo Sasaki, October 2, 1942

I felt like a prisoner because they had four watchtowers, and the soldiers with their guns, you know, was watching from on top of the tower. And anybody try to go out, not escaping, but try to go out, they shoot you, without giving any warning.

- Eddie Sakaoto (And Justice for All)

I am weary of camp, the desert, the dust and the heat!!!! Words of faith and hope I cannot sincerely find in my heart… And yet, we alone of the world are not suffering…. We are but a few of the millions…. We must wait with patience and faith…. Wait with the world, with hope and with a prayer for a lasting peace; a just and eternal peace, which must come, and come soon.

- Yoshiko Uchida, Letter to mother, September 27, 1942

Quotes from:

John Tateishi, And Justice for All: An Oral History of the Japanese American Detention Camps

Hideo Sasaki interview by Charles Kikuchi, Jan. 26, 1944, The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley

Yoshiko Uchida papers, UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library

Patricia Miye Wakida is a fourth generation Japanese American artist, writer, and community historian. For the past 15 years, she has worked with numerous cultural institutions such as the Japanese American National Museum, Discover Nikkei, the Oakland Museum of California and the Densho Encyclopedia project.

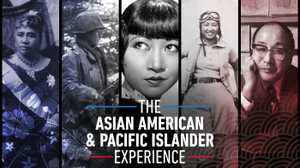

Explore our new collection featuring a selection of films documenting the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Experience — along with articles, digital shorts and original features exploring America’s continued struggle with democracy, inclusion and justice for Asian Americans, and celebrating the contributions of AAPI Americans to the American story.