William Randolph Hearst and McCarthyism

Hearst was a major force behind the anticommunist crusade that was underway for years before McCarthy arrived on the scene.

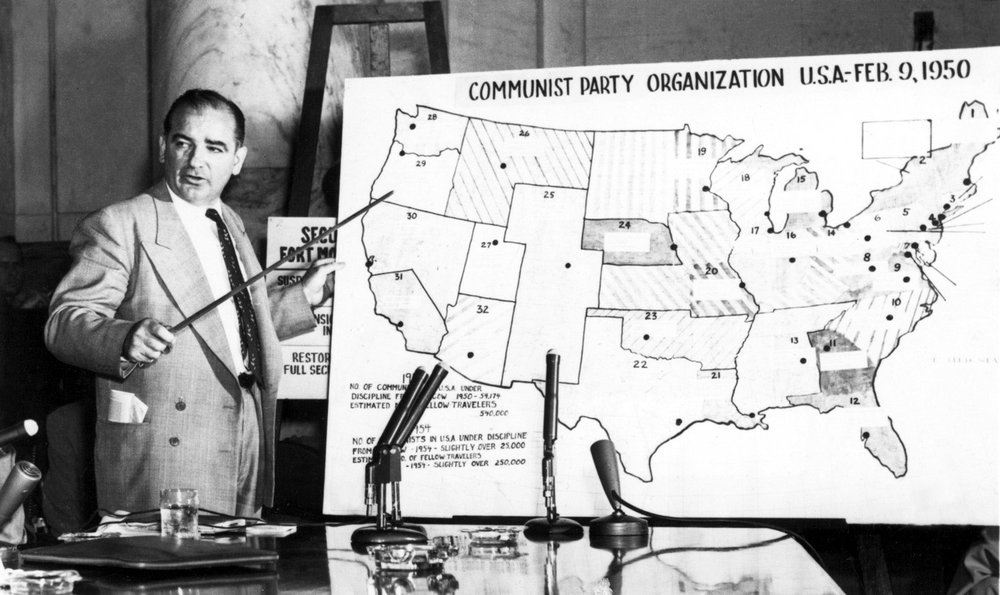

William Randolph Hearst was nearly on his deathbed on February 9, 1950 when a little known junior senator from Wisconsin named Joseph McCarthy announced during a routine political speech to a group of Republican women in Wheeling, West Virginia, that he held in his hand a list of 205 Communists in the State Department. Over the next few days the numbers fluctuated. Was it 57 reds? Or 81? The names and numbers didn’t matter. It was the boldness of his charges and their supposed specificity that threw the Democratic administration into a tizzy and made McCarthy so notorious that his name became synonymous with the longest and most widespread episode of political repression in American history.

Yet Joe McCarthy did not invent McCarthyism. William Randolph Hearst was the main progenitor of the anticommunist crusade that had been under way for years before McCarthy arrived on the scene. The most important media mogul of his time, Hearst had used the wealth he inherited from his father’s fabulously successful mining operations to buy up nearly 30 newspapers in the nation’s largest cities and create a syndicate of cartoonists, journalists and columnists that reached nearly 20 percent of the American population at a time when the daily press was the primary source of political information in the country.

Beginning in the mid-1930s, Hearst had been waging a major campaign to eliminate communism and all the individuals, groups, and ideas associated with it from any position of influence within American society. Together with his key subordinates and a group of dedicated anticommunist activists and writers whom he often bankrolled, Hearst presided over the framing of a narrative about how American communists had undermined the New Deal administration. In the process, the conservative press lord created a formidable network of professional red-baiters who brought that narrative into the political mainstream during the early Cold War.

Though late to the party and operating at a time when Hearst was largely out of the picture, McCarthy embodied the older man’s political legacy. Not only did the Wisconsin senator promote Hearst’s anticommunist agenda, but he also received the direct support of the counter-subversive network that the powerful publisher had created. Its members gave McCarthy enormous publicity, as well as the ideological ammunition, information and personnel to back up his allegations. That collaboration between McCarthy and Hearst’s network deformed American politics for several years at the height of the red scare in the early 1950s.

By the time they petered out in the late 1950s, the anticommunist purges we now call McCarthyism had victimized thousands of people, gutted the American left and narrowed the entire political spectrum. It was no longer possible for respectable citizens or mainstream politicians to discuss economic inequality or criticize the militarization of the Cold War. But, unlike political repression in other countries, McCarthyism did not rely on violence to quash dissent. Economic sanctions sufficed.

Only two people—Ethel and Julius Rosenberg—were killed and several hundred went to prison. How many men and women lost their jobs or were otherwise punished we may never know. One scholar estimated there may have been between twelve and fifteen thousand such people, but because so many dismissals and blacklists were secret, the true toll may well be larger. Most of these individuals posed no threat to American security. They were law-abiding citizens who, admittedly, had—or, more often, once had—some kind of connection to communism, but by the late 1940s and 1950s were targeted only because of their present or past adherence to an unpopular left-wing movement.

The repression they faced operated in accordance with a two-stage procedure: first, the supposed subversives were identified, then they were punished. The first stage was usually handled by official bodies like investigating committees and the FBI or else by the press. Public and private employers managed the second stage. Because it was common to identify McCarthyism mainly with the highly publicized congressional hearings and criminal prosecutions of its first stage, the red scare’s bifurcated nature allowed most of the institutions and individuals that quietly administered the economic sanctions of its second stage to escape responsibility for their collaboration with the witch-hunt.

Hearst and his coterie of professional anticommunists, along with J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI and ambitious politicians like McCarthy, were crucial to the success of these operations. Not only did they finger the alleged culprits, but they also constructed and then disseminated the scenario that justified punishing them in the name of national security. Hearst pioneered the anticommunist crusade, and McCarthy made his career within it. Together they enabled a myth about communist subversion in the United States to dominate domestic politics for nearly two decades.

Parallel paths

William Randolph Hearst and Joe McCarthy had much in common. They both craved political power and, in the senator’s case, public attention. In addition, they both owed much of their considerable success to an adroit ability to manipulate the media and ascertain the public’s moods—plus a willingness to bend the truth. And, of course, they both devoted themselves obsessively to the anticommunist crusade.

Born with a silver—not to mention gold and copper—spoon in his mouth, Hearst had dropped out of Harvard in the late 19th century to begin the career that was to make him the most powerful publisher of his era. Joe McCarthy had also dropped out of school—to raise chickens. After returning to high school at the age of twenty-one and working his way through college and law school, he entered political life. His ascent from chicken farmer to senator actually exemplified the American dream of the kind of upward mobility through politics that talented and ambitious (and, in McCarthy’s case, unscrupulous) white farm boys could aspire to in the first half of the 20th century.

Though they came from wildly different backgrounds, the two men also shared the same political trajectory, moving from left to right until they came to embrace such a ferociously reactionary form of anticommunism that they ended up in isolation on the extremist fringes of American politics. Initially, however, both began their careers as Democrats. After a characteristically sleazy campaign, McCarthy became a small town judge, quitting to join the military during World War II. Then, motivated entirely by opportunism, he switched parties, taking advantage of his status as a veteran and the 1946 Republican surge to run for the Senate.

Equally ambitious, Hearst used his great wealth and his vast media empire to expand his political clout, while promoting his personal ideological campaigns. From the start, he exercised tight control over his journals’ contents, dictating their editorial policies and specifying how they should present the news. During the height of his influence in the 1930s, he even wrote many of those newspapers’ editorials himself and put them on the front pages. Even when he kept a lower profile, the editors and reporters who worked for him usually shared their employer’s views or simply deferred to them.

From populist to conservative

He had started out as a populist, fully enmeshed in the progressive movement of the early 20th century. His newspapers attacked the reigning plutocrats of the gilded age and pressed for key progressive reforms, while Hearst himself, served two terms as a congressman from New York and then ran unsuccessfully for mayor and governor as a left-wing Democrat. By the 1920s, however, as his press empire expanded, he began to modify his hostility to the capitalist class. As his biographer David Nasaw put it, Hearst “had become more and more of a conservative as he aged, for the very simple reason that he had more and more to conserve.”

Still, even as he veered to the right, Hearst, nonetheless, remained a capital “D” Democrat. In 1932, for example, despite his unease about Roosevelt’s internationalist proclivities, he backed him with both financial and editorial support. In return, he expected FDR to bring him into his inner circle. That did not happen. Instead, the New Deal began to lean left. The president’s support for organized labor and his rhetoric about taxing the rich soon alienated the increasingly conservative publisher.

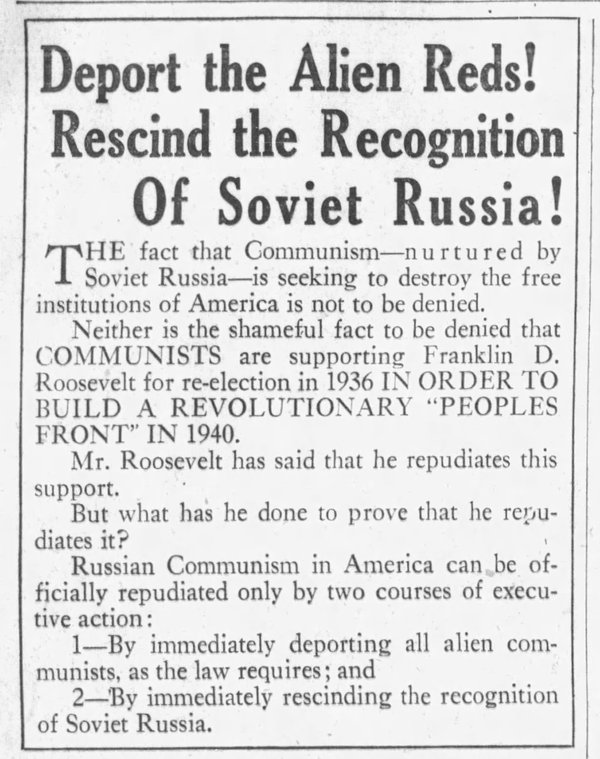

By the mid-thirties, as Hearst’s rift with the White House deepened, anticommunism entered the picture. Making connections between labor unrest, communism and the New Deal administration quickly became a staple of the Hearst empire’s political culture. Ordering his key lieutenant to “make a powerful crusade against Communism,” the increasingly right-wing publisher suggested using “exposure and … arousing the public to its dangers.” Hearst then recruited a stable of professional red-baiters to supply information about the supposedly pro-Soviet proclivities of whatever leftists and liberal New Dealers his journalists and columnists were encouraged to attack. He also pressed his subordinates to engage directly in that campaign. The corporation’s West Coast chieftain, John Patrick Neylan, for example, took charge of the campaign against the left-wing longshoremen’s 1934 general strike in San Francisco. Denouncing the strike leaders as “subversives,” Neylan mobilized right-wing vigilantes, the business community police, and the Berkeley football team to break the strike.

Hearst himself soon became one of the country’s most recalcitrant anti-union employers, provoking walkouts by his reporters when he refused to recognize the newly organized Newspaper Guild. He also turned increasingly hostile to FDR, whose New Deal administration, he claimed, was infested with reds. “Mr. Roosevelt declares that he is not a Communist, but the Communists say he is one,” the fiery publisher wrote in a front-page editorial in the fall of 1936. “The Communists ought to know. Every cow knows its own calf.” His papers also launched campaigns against allegedly pro-Soviet college professors and called on state and local governments to impose loyalty oaths on public school teachers. Over the next decade and a half, these campaigns spread throughout the country, culminating in 1949, when Neylan, then on the Board of Regents at the University of California, succeeded in imposing an anticommunist loyalty oath on the institution’s faculty.

At the same time as Hearst and his minions were inveighing against the communist infestation of the New Deal, they were also developing a narrative about foreign affairs that within a decade would provide McCarthy and his allies with their most potent ammunition. Throughout his career, Hearst was to espouse a blustery and essentially isolationist form of nationalism. At the turn of the 20th century, for example, he championed American empire building and its concomitant racism in Latin America, the Caribbean and the Pacific. At the same time, like many other Western and Midwestern Progressives, inveighed against the European powers’ colonial ventures and their ties to Wall Street and the Eastern establishment. Then, when World War I broke out, he denounced the conflict as an internal squabble within the Old World that the United States should stay away from. He was equally opposed to the Treaty of Versailles’ punitive treatment of Germany and generosity to Japan. Not only did he oppose the League of Nations, but, heartened by the public’s hostility to such international entanglements, he also led a successful campaign against Roosevelt’s attempt to join the World Court.

So strong was the militant publisher’s distaste for the postwar settlement that, even as Hitler began to aggressively unravel the Versailles treaty, Hearst continued to commission articles by authors – including Hitler and Mussolini – who would argue against American intervention in Europe. Hearst was no fascist. He had close personal and economic ties to Hollywood’s powerful Jewish moguls and was appalled by Hitler’s anti-Semitism. Still, he sought to curry favor with the Fuhrer, apparently in the hopes that their mutual enmity to the status quo might encourage him to moderate his treatment of the German Jews.

Pearl Harbor shattered such illusions. Even so, Hearst and his isolationist circle of anticommunist professionals attacked the Roosevelt administration’s conduct of the war. They transformed their “America First” orientation into an “Asia First” one. They opposed aid to the Soviet Union and urged Washington to drop its emphasis on the European theater and prioritize the Pacific one. Once the war ended, these former isolationists took up the cause of the Chinese Nationalists in their doomed struggle against the Communist revolution.

That conflict was to supply Hearst’s right-wing allies and employees with one of their most potent weapons against the Truman administration. They developed a narrative about the loss of China that attributed the communist victory there to the machinations of a small group of State Department officials who undermined American support for the Nationalists and, thus, let China fall to the reds. It was a preposterous assertion. China was not America’s to lose. And the diplomats in question were realists, not Russian agents. But truth did not prevent that scenario from becoming the centerpiece of Joe McCarthy’s early charges of betrayal in high places.

In fact, the specific allegations about the loss of China that propelled McCarthy into the history books had already become central to the Republican Party’s partisan campaign against the Truman administration. Once their unexpected defeat in the 1948 presidential election forced the GOP’s leaders to realize that the American voters would not buy into their repudiation of the New Deal’s reforms, they signed onto the anticommunist crusade that Hearst and his circle promoted.

By the late 1940s, with the intensifying Cold War providing credibility and a sense of urgency, the “communists-in-government” narrative resonated with a public unsettled by Washington’s seemingly unsuccessful foreign policy. How else to explain the evidence of Soviet espionage during the war or the Russians’ detonation of an atomic bomb or the Communist takeover in China? As thousands of loyalty investigations, trials, and hearings exposed alleged subversives everywhere from Hollywood to Harvard, ambitious members of the Republican right wing, Joe McCarthy among them, found their calling.

By then, Hearst was no longer active, but his political legacy was flourishing. Richard Berlin, who replaced the old man as president of the Hearst Corporation in 1943, was a true believer. He socialized with McCarthy and the other members of what one of them called, not entirely in jest, the “Ancient Order of Red-Baiters,” and was known to boast, as the anticommunist crusade of his predecessor came to dominate American politics: “the Hearst newspapers can shout ‘hurrah.’” Today, as conspiracy mongering suffuses the American political scene, it may not have been the last hurrah.

A retired professor of history at Yeshiva University, Ellen Schrecker has written extensively about the Cold War red scare and American universities. Among her books are No Ivory Tower: McCarthyism and the Universities (1986), Many Are the Crimes: McCarthyism in America (1998), and The Lost Soul of Higher Education: Corporatization, the Assault on Academic Freedom, and the End of the University (2010). She is currently writing about professors and politics in the 1960s and 70s.