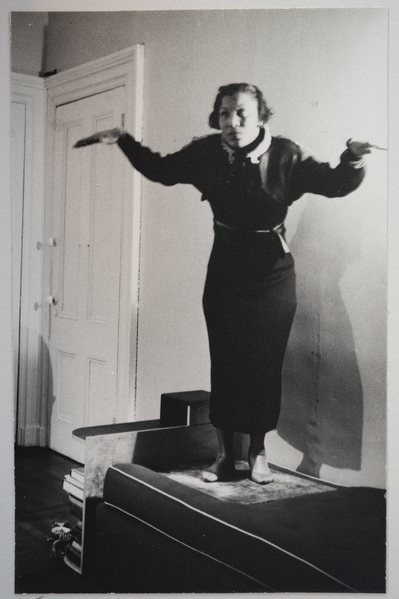

What Happened When Zora Neale Hurston Studied Voodoo in Haiti?

The renowned author and anthropologist went to the island nation in search of its religion—and its zombies

When author and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston arrived in Port-au-Prince, Haiti in September 1936, she wasted no time penning a letter of thanks to her sponsor. “I can’t tell you how much this chance means to me,” she wrote to the Guggenheim Foundation of the fellowship that would allow her to travel to Haiti for six months. A year earlier, Hurston had abandoned a doctoral program in anthropology at Columbia University when funding fell through. Now, the Guggenheim grant would allow her to do the work she was unable to pursue under formal academic auspices. “I am straining every nerve to the goal,” she vowed.

By then a celebrated figure of the Harlem Renaissance, Hurston was going to the island nation to study and write about voodoo practices. Western audiences held only the most salacious stereotypes of vodou, a folk religion originated by the enslaved, then escaped African diaspora of the Caribbean. For many Americans, their introduction to voodoo was The Magic Island, a 1929 book by white journalist William Seabrook. Seabrook’s bestseller traded in cliché; in a representative description of a voodoo ceremony The Magic Island described “screaming, writhing Black bodies, blood-maddened, sex-maddened, god-maddened.” Hurston wanted to reach the same general readers, but understood voodoo’s complex spirituality as deserving of serious ethnographic inquiry.

She quickly established a homebase for herself in the Port-au-Prince suburbs and dove into her research. Hurston began by gaining the trust of houngans, the voodoo priests and community leaders who presided over the rituals and observances of their faith. Song, dance, healing, possession, raising of the dead—under the island’s most renowned houngans and chief priestesses, Hurston went straight to the heart of voodoo culture.

She learned about the loa, or gods, whose spirits animated Haitian life, and who went by different names and symbols throughout the country. Shepracticed the signatures, or symbols, of Damballah and his female counterpart, Erzulie Freida—who headed up the Rada, or good deities—until she had committed them to memory. And Hurston witnessed, at every level of Haitian society, the intertwining of a seemingly infinite voodoo entourage with Jesus, Mary, Joseph and the more familiar Christian saints, all of them forming a unique syncretic whole.

Within three months, the enormity of her undertaking became apparent. “I realize the task is huge, so huge and complicated,” she wrote to the Guggenheim Foundation, imploring them to renew her fellowship. Trying to summarize voodoo, Hurston said, was “like explaining the planetary theory on a postage stamp.” She impressed upon her sponsor the religion’s sophistication: “it is as formal as the Catholic church anywhere.”

Hurston also wrote that she had already accomplished one of the main goals of her research—collecting first-hand evidence of what Haitian Creole called zonbi. If white audiences viewed voodoo with, alternately, scorn and titillation, zombies were the embodiment of the sinister exoticism that foreigners believed permeated the island’s life. “What is the truth about zombies?” Hurston would later ask in Tell My Horse, the book that came of her time as a voodoo initiate. “I do not know,” she answered herself, “but I know that I saw the broken remnant, relic, or refuse of Felicia Felix-Mentor in a hospital yard.”

Hurston learned of Felix-Mentor in November 1936, directly from the director-general of Haiti’s ministry of health. Doctors at the hospital in Gonaives, to the north of Port-au-Prince, told Hurston that Felix-Mentor had been brought to them a month earlier after police came upon her naked along the road—29 years after being buried by her husband and son.

The doctors believed a bocor, a priest practiced in dark magic, had administered a poison that made Felix-Mentor appear to be dead, before surreptitiously returning later to “resurrect” her with an antidote. Bocor ensnared their victims, Hurston had learned, in order to put them to work as thieves, or on plantations as laborers.

When Hurston met her, Felix-Mentor cowered near a fence enclosing the hospital yard, trying to shield herself from light and attention. She uttered only broken sounds; likely the toxin she had ingested caused brain damage that left her without the power of speech. Eventually, with the doctors’ assistance, Hurston took Felix-Mentor’s photo, which shortly thereafter was published in LIFE magazine as the first known photograph of a zonbi.

How should one understand these revenants, returned from the grave, without ability to exercise independent thought or free will? In Tell My Horse, Hurston did not equivocate about the phenomenon’s existence. She had inarguably seen, with her own eyes, “the relic” of a once whole person. Neither, though, did she sensationalize. What Hurston did do was apply her protean talents, as a practitioner of both literary art and ethnographic science, to lay out the mystery of zombies; namely, by explaining how that mystery was understood by Haitians themselves.

“[Haitian] ceremonies were both beautiful and terrifying,” Hurston would later write in her memoir Dust Tracks on a Road. “I did not find them any more invalid than any other religion. Rather, I hold that any religion that satisfies the individual urge is valid for that person. It does satisfy millions, so it is true for its believers.”

The Guggenheim Foundation demonstrated its confidence in Hurston’s work by offering her a second fellowship, but after suddenly falling ill she decided to return to the United States earlier than planned. It was possible, she allowed in a letter to the Foundation explaining her decision to come home, that she had been overzealous in her efforts to delve deeper into the unknown. “[T]here have been repercussions,” she wrote. “It seems that some of my destinations and some of my accessions have been whispered into ears that heard.”

A Gonaives doctor, when she interviewed him about Felix-Mentor’s troubling case, had expressed a desire to know what constituted the drug behind Haiti’s zonbi. Hurston immediately offered her services to seek out its source, prompting an admonition against going too far to learn more of voodoo’s secrets. “Many Haitian intellectuals have curiosity,” the doctor said ominously, “but they know if they go to dabble in such matters, they may disappear permanently.” Not knowing Hurston well, the doctor could not have understood it would take more than a stern warning to scare her away. She persisted with her fieldwork in Haiti, not relenting until her health was compromised.

It wasn’t the first time that Hurston’s work had brought her close to danger. Such risk, she believed, was necessary for great reward. “Research is formalized curiosity,” Hurston said in Dust Tracks, writing what might have doubled as a personal raison d’être. “It is poking and prying with a purpose. It is a seeking that he who wishes may know the cosmic secrets of the world and they that dwell therein.”

Women lead advancements in science, technology, politics, sports and activism—often fighting against inequity and opposition at every turn.

In this collection, explore films, interviews, articles, image galleries and more for an in-depth look at notable female figures in American history.

An AMERICAN EXPERIENCE collection featuring a selection of films documenting the African American Experience — along with articles, digital shorts and original features exploring America’s continued struggle with race, democracy and justice, and celebrating the contributions of Black Americans to the American story.