Castro and the Cold War

Fidel Castro's life story is not the story of the leader of a poor underdeveloped nation struggling to survive against the fierce opposition of the United States. For four decades, Castro purposely stood at the center of the dangerous game the United States, the Soviet Union and sometimes China played for political pre-eminence in the Third World. By deftly manipulating the opportunities afforded Cuba by the Cold War, he managed to turn his island into a launching pad for the projection of his leadership throughout the world.

Soviet Protection

Castro's courtship of the Soviet Union began shortly after the revolution with a visit to Havana by Soviet Vice Premier Anastas Mikoyan. As he took on the United States he knew he needed Soviet protection in order to survive. The Soviets played a cautious game, but could not pass up an opportunity to gain a toehold in the Western Hemisphere, ninety miles from the United States. At the end of Mikoyan's visit, the Soviets agreed to buy Cuban sugar in exchange for Soviet oil. The United States, already concerned with Castro's anti-American rhetoric, saw the agreement as a betrayal, and asked U.S. companies in Cuba not to refine the Soviet crude oil. Relations began spiraling down, until their final break in January 1961.

Nuclear Crisis

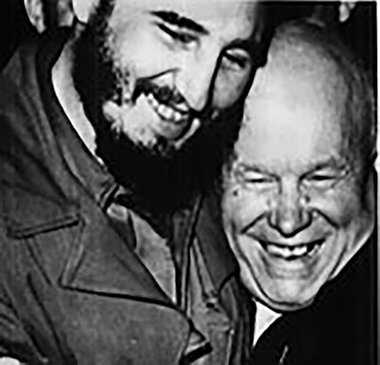

In December 1961, only a few months after the U.S.-sponsored exile invasion at Bay of Pigs, Fidel Castro declared himself a Marxist-Leninist, obligating the Soviet Union to protect his new, vulnerable socialist nation. Shortly thereafter he asked the Soviet Union for weapons, advisers, and even Soviet soldiers. The Soviets proposed a different defense -- medium-range ballistic missiles. Castro agreed. When in October 1962 American U-2 spy planes photographed missile sites in Cuba, the world approached the brink of a nuclear confrontation. As the tensions of the Missile Crisis escalated, Castro wrote Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev urging him to use the missiles and to sacrifice Cuba if necessary. Unbeknownst to the Cuban leader, Khrushchev had already reached an agreement with President John F. Kennedy to withdraw the missiles, without consulting Castro. The Cuban leader found out from a friend, the editor of the newspaper Revolución, Carlos Franqui. Castro was infuriated to discover that the Soviet Union would treat Cuba just as the United States had -- as an insignificant island in the middle of the Caribbean.

Covert War

In the end, Castro emerged a winner. President Kennedy secretly pledged to Khrushchev that the United States would not invade Cuba. Yet the Cuban revolution continued to face threats, as a U.S. covert war code-named Operation Mongoose proceeded. And the economic embargo the U.S. had imposed in 1961 continued unabated.

Committed to World Revolution

Castro was fiercely committed to creating his own revolutionary world and to fighting imperialism whenever and wherever the opportunity arose -- in Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East. "Any revolutionary movement, in any corner of the world, can count on the help of Cuban fighters," he told a audience of Third World revolutionary leaders in early 1966. When his revolutionary goals clashed with those of his Soviet benefactor he nevertheless pursued them. Among Kremlin officials he became known as "the viper in our breast."

Defeat and Betrayal

Castro's world revolution eluded him. His guerrilla armies were defeated by U.S. counterinsurgency forces and betrayed by Soviet-run Communist parties the world over. Most poignantly, in Bolivia, Che Guevara Castro's chief instrument of world revolution, met his death in 1967.

Good Neighbors

As the Cold War settled into détente in the early 1970s, Fidel Castro, following the Soviet line, began to soften his own antagonistic rhetoric against the United States. "We are neighbors," he told reporter Barbara Walters in 1974, "and we ought to get along." Cuban and American officials met secretly at La Guardia Airport and at the Hotel Pierre to work out a rapprochement. When Secretary of State Henry Kissinger announced in 1975 that the U.S. was ready to "begin a new relationship," the two nations stood on the brink of an agreement.

Castro's Choice

Then, 15 years after the triumph of the Cuban revolution, Fidel Castro made what was perhaps the most important choice of his life, one which would determine the future of Cuba-U.S. relations into the 21st century. In 1974-75, just as the normalization of relations between the U.S. and Cuba seemed imminent, Fidel Castro saw an opportunity to rekindle his international revolution.

Angola

After five centuries as a colony of Portugal, Angola in West Africa was due to receive its independence in November 1975. The country edged toward civil war as three separate groups bid to rule the country. Cuba had been supporting the Movement for the Independence of Angola (M.P.L.A.) since the 1960s. The Marxist leader Agostinho Neto had close ties to Havana and was favored by the Cubans. Castro faced a choice: intervention in Angola or relations with the United States. On November 7, 1975, he personally saw the departure of an airlift taking Cuban special troops into Angola's capital, Luanda, followed by two passenger ships carrying regular troops into the field of battle. When Cuba took the initiative, Moscow followed with support. "They've made a choice which, in effect, and I do mean very literally, has precluded any improvement in our relations with Cuba," President Gerald Ford said.

Afghanistan

Angola launched Castro onto the world stage. In the words of Cuban analyst William Leogrande, "the Cuban intervention in Angola identifies Cuba as a country that is willing to take a risk, willing to put its own interests on the line, willing to provoke a confrontation with the United States in support of national liberation in Africa." On the strength of his wild popularity in Africa, Castro, in September 1979, was elected leader of the Non-Aligned Movement. That October he traveled to New York to address the U.N. General Assembly, demanding an international redistribution of wealth and income in favor of the poor countries of the world. "Those months in the fall of 1979 were the apogee of his power," CIA analyst Brian Latell later observed. "How can you be a loyal, dependable Soviet ally and accept about $6 billion of Soviet assistance annually, and at the same time be the leader of the non-aligned nations? Well, Castro was able to carry out that exquisite, seemingly impossible balancing act." Then, on New Year's Day 1980, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, a non-aligned nation. Castro's foreign policy received a crushing blow.

Latin America

President Ronald Reagan came into office determined to fight the spread of Communism, beginning close to home. The Sandinistas' 1979 victory had been a huge triumph for Fidel Castro. A leftist regime, loyal to Cuba, was the foothold he had been looking for since the 1960s. Now he could support a growing insurrection in neighboring El Salvador and in Guatemala. In 1980 he acquired another ally, Maurice Bishop in the Caribbean island of Grenada. The Reagan administration went on the offensive. Reagan tightened the U.S. economic embargo, funded the Contras to wage war against the Nicaragua's Sandinistas, invaded Grenada in 1983, and launched a campaign to expose Cuba's human rights record. Castro, in turn, put Cuba on high alert, calling the Reagan administration "a reactionary extremist clique," waging "an openly warmongering and fascist foreign policy." Reagan checked Castro's advances in the Northern hemisphere. But once again, it was the superpowers who would determine Fidel Castro's fate.

The End of the Cold War

In 1985, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev launched glasnost and perestroika, economic and political reforms designed to save Communism and revive the Soviet Union's economy. Castro rejected Gorbachev's reforms, which he believed "represented a threat to fundamental socialist principles." But even Gorbachev's reforms could not save Communism, and in 1991, the Soviet Union collapsed. For Castro, it was an enormous blow. "To speak of the Soviet Union collapsing is as if to speak of the sun not shining," he had said. And the sun went away. Castro lost more than $6 billion in annual economic assistance. The socialist world, the world he had chosen to join, had come to an end.

"Like a man at the horse races he bet all his money on a horse." Cuba critic Ricardo Bofill has said, "And he bet on the wrong horse."

*This article was originally published on the site for the 2005 American Experience documentary Fidel Castro.