Goldsboro, 1961

When All That Stands Between the World and Nuclear Disaster Is the Flip of a Switch

''Bombs are relatively dumb.'' says Bob Peurifoy, former director of weapon development at Sandia National Laboratories. “They sort of think that if you drop the bomb out of the bomb bay, you must have intended to do that.” At that point, all stands between the world and nuclear disaster may be the flip of a switch — literally.

This was the case on January 24, 1961, when a B-52 bomber carrying two powerful hydrogen bombs took off on a routine mission over Goldsboro, North Carolina. During the mission, the plane experienced a fuel leak, and suddenly the B-52 began to break apart mid-air. As the fuselage was spinning and heading back towards earth, the centrifugal forces pulled on a lanyard in the cockpit — exactly as a crewmember would if he wanted to release its hydrogen bombs over enemy territory. One of the weapons in particular went through all of its arming steps to detonate, and when it hit the ground, a firing signal was actually sent.

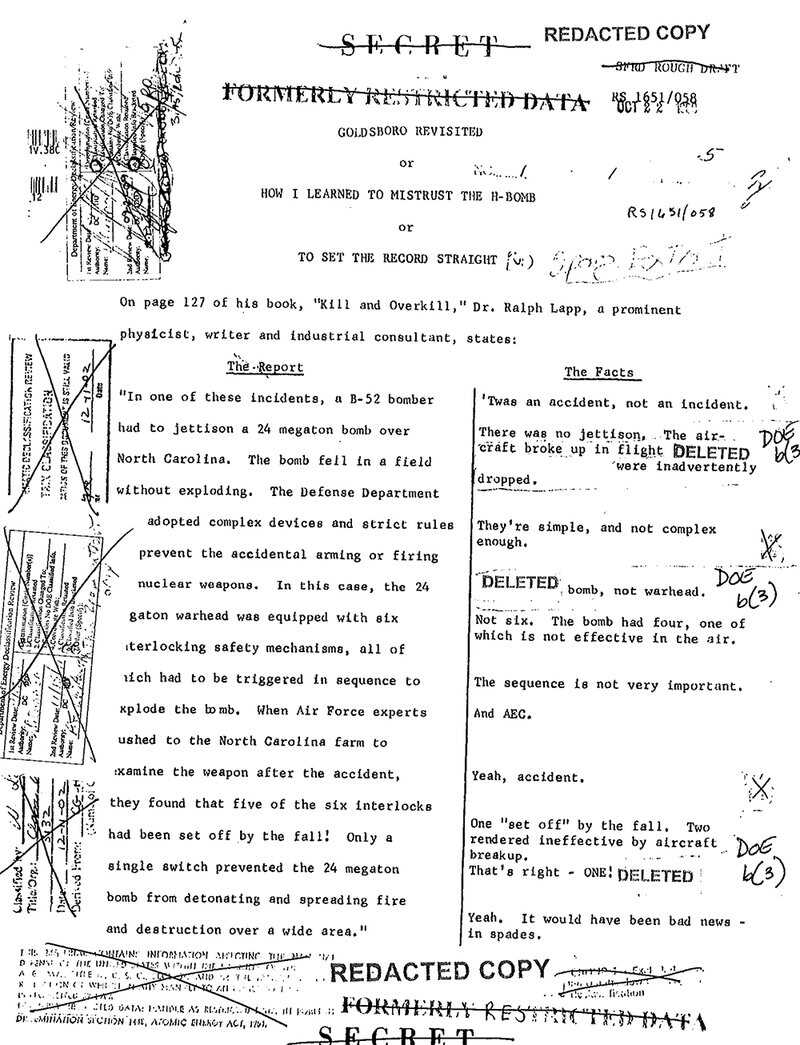

''Only a single switch prevented the 24 megaton bomb from detonating and spreading fire and destruction over a wide area,'' wrote Dr. Ralph Lapp, a physicist who participated in the Manhattan Project, in his 1962 book Kill and Overkill. But for a long time, it was unclear to the public just how dangerous that event, now known as the ''Goldsboro Incident,'' really was.

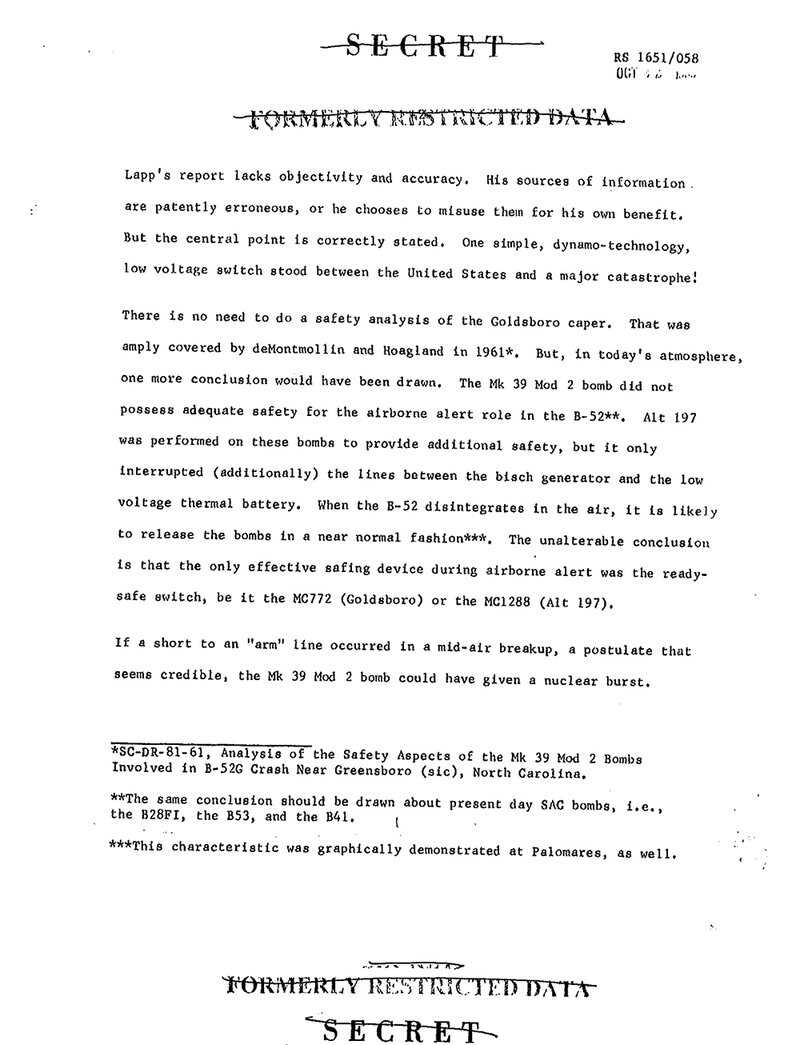

Reading Lapp's report in 1969, Parker F. Jones, then-supervisor of the nuclear weapons safety department at Sandia, criticized Lapp in a classified memo for not being objective and accurate enough. Jones’s comments appear alongside Lapp’s assessment in the document below, obtained by journalist Eric Schlosser while researching his book Command and Control, the basis of the American Experience film.

Read document below.