Interview: Optimism in the 1920s

Robert Sobel, Historian

"What will they think of next!” was a 1920s saying, because new things were continually coming out. And there were new things which you could enjoy, not just for the few. So it was a period of high hope. That’s why the depression was so severe — because we started so high, we fell so low…

[In the 1920s] every part of the economy did well, except for coal mining and certain parts of agriculture. But this was a period in which the American household gets the washing machine, gets a refrigerator, goes off gas light and gets electricity in some cities, in which the family buys a car and goes on a long vacation. This didn’t occur before the 1920s.

In 1920, for the first time, the census showed that a majority of Americans lived in cities. We were becoming an urbanized society. And if you lived in a city in 1925, ’26 or thereabouts, you had all these things going for you. In addition, you were getting your first vacation. People didn’t get vacations before the 1920s. You learned how to buy goods on time, so you didn’t defer your expectations. You were working a five-and-a-half day week, not a six-day week… So things looked pretty good.

John Kenneth Galbraith, economist

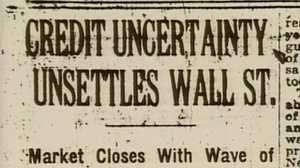

One of the things you must understand about 1929 and the antecedent years, as about any speculative episode, is the danger… in attributing intelligence to the simple fact that people are associated with large sums of money or large financial operations. We don’t ask whether they’re intelligent. We say, they’re associated with all this money, so they must be intelligent. We attribute intelligence to association with financial operations. And only afterwards do we discover that error and that the people involved can be extremely successful in gulling themselves. That they can be in effect, and I use the word advisedly, marvelously stupid.

I used to be quite an optimist… I thought that by keeping the memory of the 1929 crash alive we would have a warning against the kind of feckless, fatuous optimism which caused people to get in and shove up the markets and shove it up more and get carried away by the illusion of ever-increasing wealth. I’ve given up on that hope because we’ve had it happen too often again since.